American cities have had basically the same metro systems for the past 20 years. With the notable exception of Honolulu, which finished the first phase of their new heavy rail line in 2023, American cities have eschewed building high capacity heavy rail. Instead, cities like Milwaukee, Kansas City, and Denver have instead opted to build light rail systems. Even Dallas has only been able to muster a light rail system for their transit, despite being the fourth most populous metro area in the United States with nearly 8 million people. Why can’t American cities seem to build actual metros anymore?

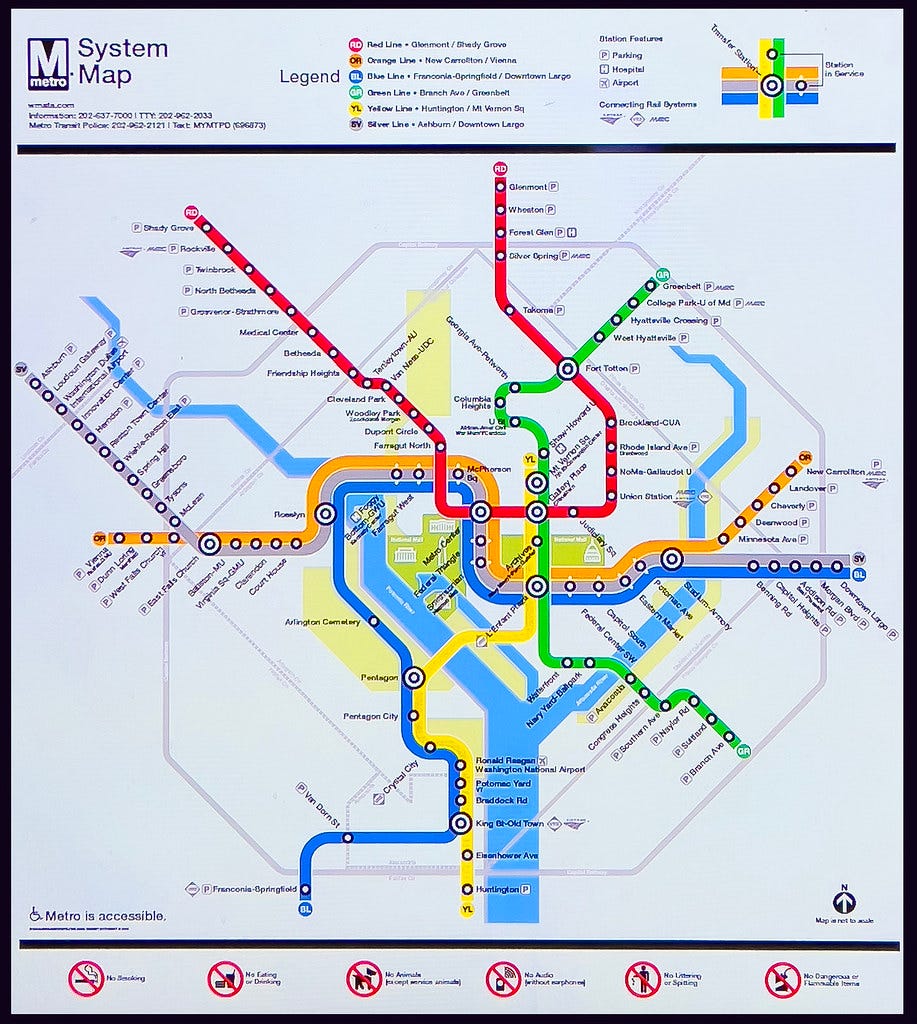

Or can’t they? In November of 2022 Washington DC finished the Silver Line, an extension of the WMATA metro system which extends to Dulles International Airport. It is the first heavy rail extension to the system since the Green Line began service in 1991. How was DC able to build a new metro line when this has been seemingly impossible for most of the country? What does it take to overcome the hurdles between our cities and metro systems?

When Washington D.C. was planning their metro system in the 1960s, they surveyed the surrounding jurisdictions about where metro stations should be located. Montgomery county officials selected locations based on future plans for the region. The Red Line would go through Bethesda, which went from a sleepy exurban town to a bustling center of business. Virginia, on the other hand, selected locations with existing population bases, like Arlington and Fairfax. Though the population was increasing towards the new airport, it was still mostly suburban. Virginia officials didn’t deem such low densities worth serving with a heavy rail metro.

In hindsight, this proved to be a mistake. Tyson’s corner is now the headquarters of over a dozen companies, including Capital One, Freddie Mac, and Hilton Worldwide. It has also become a hub for tech companies, from small startups to giants like Adobe. All of this growth is on top of the offices for defense and other federal contractors which are all over the area around DC. The corridor became one of the fastest growing areas in the United States! And unlike Maryland communities like Bethesda, there was no rapid transit service. So instead of walkable transit oriented development, Tyson and surrounding communities sprawled out around massive highways with some of the worst gridlock in the nation.

Americans aren’t strangers to car dependent sprawl and traffic gridlock. But the route to Dulles and the area around Tyson were extreme. First, an access highway connecting to I-66 supplemented the original small access road off of Virginia State Route 267. When that wasn’t enough, the access road turned into the four lane Dulles Toll Road. A few years later VDOT widened the road to six lanes. Then they added an HOV lane in each direction. By the end of the 1990s, the highway took up the entire available right of way. And traffic was still only getting worse.

The traffic situation was so desperate that, in 1998, Raytheon engineers wrote and submitted an unsolicited proposal for the construction and operation of a Dulles Corridor Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system. The increasingly congested traffic without any more right of way left to expand roads combined with the steady urbanization of the region to produce at least high level agreement that the only way forward was some kind of public transit.

While those Raytheon engineers just wanted a way to get to work without sitting in traffic, they didn’t know that officials had been slowly but surely laying the groundwork for future transit development. As early as 1968, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) officials reserved the median of the access highway right of way for a future transit line. Throughout the 70s and 80s a wide variety of actors authored a huge number of studies examining a multitude of transit options to connect Dulles to the DC Metro. These studies were comprehensive. They examined different transit modes, different routes, and different funding models.

This was the first good sign for the future of transit through Tyson to Dulles. Even though officials decided against including Dulles in the original transit plan, they did not completely close off that option for the future. Instead, officials kept a substantial variety of potential options open to study and consideration. These studies didn’t take anything for granted and explored everything from transit modes, to routes, to funding models. The Transportation Equity Act also earmarked $86M to future transit improvements along the corridor, with a contingent commitment up to $217M. Compare this exploratory model to the development of nuclear power. Part of the reason we got stuck with light water reactors, when other technologies are likely superior, is because Admiral Rickover committed too early to the technology. DC Metro wasn’t going to make that mistake here.

All of this prepared VDOT to respond quickly to Raytheon’s unsolicited proposal. In a month, VDOT published a solicitation for competing proposals. But most parties involved preferred advancing directly towards a heavy rail line, rather than the incremental BRT to rail plans proposed by Raytheon and others. Solicitations for public comment indicated a public preference for rail connection over other transit options.

But, as we’ve discussed before, rail is substantially more capital intensive than BRT. The initial estimate for the project was around $4B. Where were they going to get all that money? The Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority (MWAA) took charge of the project, so they would put in some money. For their share, they increased the toll on the access road by 50 cents. Although this would eventually raise enough to pay for nearly half of the project, the MWAA would need to take out loans in the meantime.

Fairfax county devised a special tax district called a Transit Improvement District (TID). Because transit bring increased revenues for businesses, more homes, and more offices, it also usually increases land values nearby. The TID would capture some of this increase in value by instituting a tax increase of 20 cents for every $100 of land value. But even this idea would only generate about $400M, not enough to fund the rest of the project. So the last source of funding would be $900M from the federal government.

But getting funding from the federal government isn’t a sure thing. Projects funded by the federal government have to walk a fine line. First, of course, they have to be substantial enough to justify getting federal help. But at the same time, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) is reticent to fund projects that are too expensive. They don’t want to fund projects that overly ambitious and likely to fail, and the FTA may simply not have enough funds available to fund a project that is too expensive. So while the project required federal funding, doing so meant a whole extra set of political hurdles to overcome.

But overcome them proponents did. To ease the hurdles to federal funding, so the MWAA split the project into two phases. Phase 1 would go to Reston, while phase 2 would extend the line to Dulles and through to Ashburn as the terminus. But before even getting federal funding, the TID had to pass.

The TID required land owners representing 51% of the total land value in the TID to vote in favor of it. Fortunately, the project was locally popular, and a group of landowners called the Land Owners Economic Alliance for the Dulles Extension of Rail (LEADER) did quite a bit of leg work to get the votes. They got the votes and it was approved by the Virginia Legislature. But town councils with land in the TID area also had to approve it, and the Herndon Town Council unanimously voted against it. They essentially had veto power, and without the TID, the Silver Line wouldn’t have enough funding. Land owners in Herndon had two concerns: 1) that it wasn’t fair for everyone along the route to pay the same even though phase 1 businesses would benefit sooner and more than phase 2 businesses and 2) that phase 2 might fail and only phase 1 get built, meaning they would pay and only competing businesses further east in Tyson would benefit.

Herndon land owners weren’t against the rail line, or even against the TID. They just wanted it administered more fairly. But their veto meant the county was dangerously close to federal funding deadline that only came once every six years. So if they were to come to a compromise, they would have to do it fast. And they did. A compromise was quickly brokered between the county, LEADER, and representatives from landowners in the phase 2 area: creating a second TID for phase 2.

This compromise, and its expediency, is what makes Herndon’s veto different from what we see from NIMBYs. Herndon wanted the Silver Line as much as every other town on the proposed route. But they had a specific and reasonable concern. By giving each town essentially veto power, it ensured that every town had their voices heard and their concerns addressed. It is important to keep in mind that this was, in part, only possible because support for the idea itself was so broad, but it demonstrates how good democratic processes are taking disagreement and turning it into policy improvements. The funding proposal was genuinely unfair, and the change made it better. As evidence of this, the new TID proposal was hashed out and adopted in a matter of mere months to ensure the project would still meet the deadline to apply for federal funding.

But that wasn’t the only major hurdle. And the requirement for federal funding rears its ugly head again. To save money on what is a very long extension, about 23 miles, most of the track is raised above ground. But in the busy area of Tyson, residents and businesses wanted the train to be underground. So the MWAA commissioned a study, which indicated that tunneling under Tyson would increase the cost of the project by $500M. This cost increase would exceed the FTA’s cost-effectiveness criteria and threaten federal funding for the project. In fact, when local and state officials representing the Silver Line project met with the FTA Administrator, James Simpson, he announced the Silver Line would receive a medium-low rating. Such a rating is too low to qualify for federal funding. This essentially decided the issue, and project leaders quickly fell in line. The Silver line would be kept above ground.

Negotiations between interest groups can be good because they solve problems that might not be apparent to all groups, even if they can be frustrating and push deadlines. But that isn’t what happened with the federal government. This is similar to the problem with Albuquerque’s electric buses. Adding electric buses was a requirement for federal funding, but it reduced the flexibility of the project and added substantial delay. For the Silver Line, the cost-effectiveness requirement was too inflexible to adapt the original design to the needs of the very citizens the line was supposed to serve. And by forcing additional studies and last minute adjustments, trying to get the tunnel still increased the cost of the project by $200M!

The biggest problem with the Silver Line can therefore be traced back to its capital intensity. An unexpected consequence of which was the reliance on federal funding. This meant that the project was beholden to any inflexible requirement the FTA had for the project. Unlike citizens with a stake in the outcome, like Herndon, there was no incentive for the FTA to negotiate. But does that mean it really is better just always do cheaper projects like BRT? Sometimes yes, but sometimes, like with the Silver Line, the capacity of heavy rail is the best solution.

The Silver Line almost didn’t exist, and therefore I almost couldn’t be writing about how messy compromises and democratic negotiations actually make projects like it possible. How do other places have such a seemingly easier time building rail? The problem lies in the duration between projects. Washington DC waited over 20 years after their last addition to the metro to build a massive, long, and expensive new line. Instead, they could have done many, smaller, cheaper, extensions towards Dulles over that same period. This strategy of constantly building out transit in small increments not only keeps the capital intensity down, but it keeps total costs down too by maintaining the experience and infrastructure needed to build heavy rail. And of course, then you don’t have to go hat in hand to the federal government, at least not for as much money.

In the end, the project cost $5.7B, a 57% increase over the original budget. It may be easy to blame all of the messiness I have described here as being an impediment to better transit. After all, if we just gave the project the support and funding it needed, many of the delays, and therefore cost increases, would not have happened. But that looks at the project through rose colored glasses. The bottom line is that big, expensive projects are not simple nor universally agreeable, even in situations where everyone wants it to work out. The problems are sticky, and the messiness of politics isn’t a barrier to solving them. It is *how they get solved*. By embracing that messiness, Washington DC and Northern Virginia were able to get a new metro line while metros in other American cities are either stagnant or non-existent.