Now that we’ve decided Elon Musk isn’t the problem (just *a* problem), it’s time to think about some solutions.

A sovereign wealth fund (SWF) is an investment fund run by or on behalf of a government. Typically, states have managed excess funds as financial reserves. This money is outside of the general fund and acts as a kind of rainy day fund which a state can use to mitigate a variety of financial problems. Financial reserves have stabilized currencies, reduced debts, and paid for unexpected expenses like natural disasters.

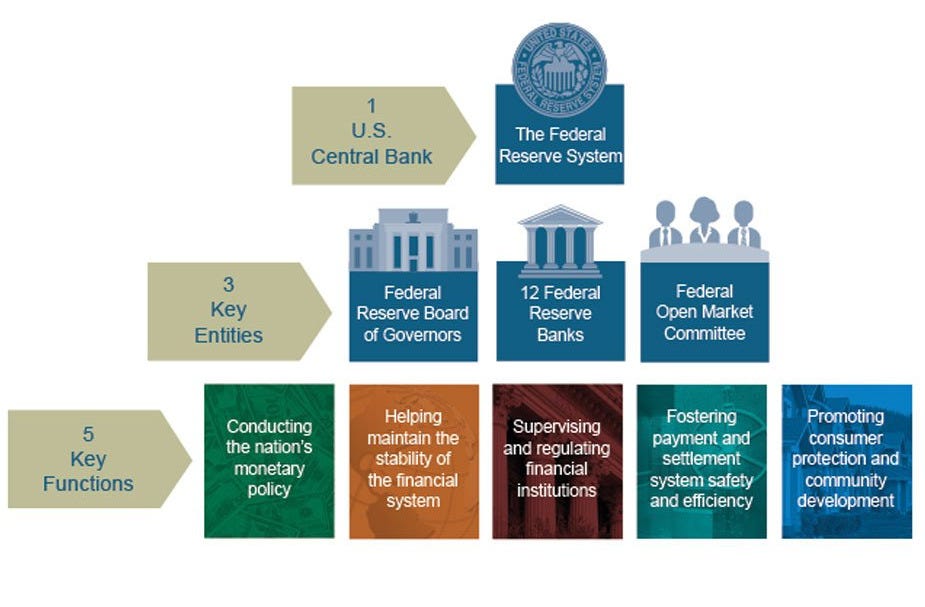

Financial reserves must be fairly liquid to meet these needs. As such, they tend to be stable, low return investments managed by central banks. This makes their use closely tied to political processes. Politicians have to be able to decide when and how to use those funds. If elected officials don’t have the authority to use those funds in response to need, then the reserves aren’t doing their job.

But financial reserves aren’t always going to work in every situation. Small economies often cannot withstand substantial capital inputs without undergoing inflationary pressure. States may also have long term goals beyond the scope of a rainy day fund. This is where SWFs come in.

SWFs tend to have two features that make them distinct from financial reserves. The first of these features is their orientation to long term, high return, financial growth rather than liquid but low return investments. This is because SWFs serve a different purpose. They turn short term financial surpluses, for example from natural resource deposits or trade surpluses, into sustainable and stable income in the future.

The second feature is that SWFs are removed from direct political control. Rather than being run by elected officials they tend to be run by professional financial managers. This separation prevents officials from using the funds in pursuit of short term political goals, which is at odds with the goal of creating long term wealth.

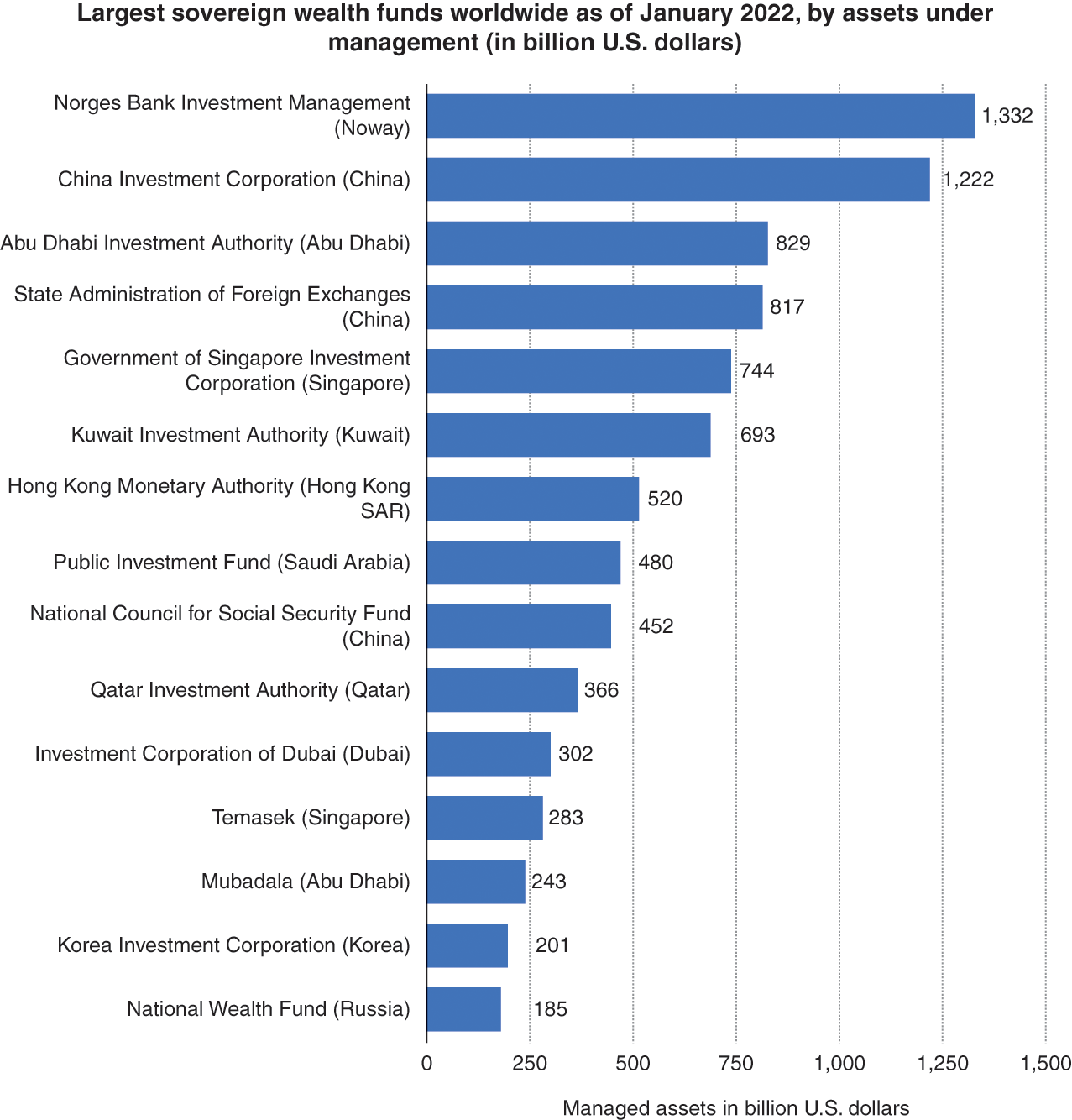

But this doesn’t mean that SWFs are separated from state policy goals. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund is the largest in the world. They are exerting their influence over the thousands of companies in their portfolio to encourage them to reach net-zero carbon emissions. China established its sovereign wealth fund, the China Investment Corporation (CIC), by taking on debt in the form of treasury bonds rather than with an existing surplus. But officials there deemed the goal of the CIC, to recapitalize domestic state-run businesses using the profits from foreign reserve investments, worth the risk of financing it through debt.

SWFs don’t need to explicitly pursue state policy goals in order to influence policy. The majority of capital coming from SWFs are from Southwestern and Eastern Asia. Norway and some resource rich states in the U.S. are the primary exceptions. This has led to the governments of Western nations to worry over the influence these foreign investors might have over their economies.

SWFs now command enough capital that their investment strategies themselves are influential in the direction of development. Given the goal of long term growth, SWFs have increasingly gravitated towards infrastructural investment. These investments are ideal because, though they have very high capital intensity and they take a very long time to mature, they can have very high payouts in the long term. While most private investors aren’t very motivated to wait 50 years for their return (they want to be alive to enjoy the fruits of their investments after all), those time spans pose no barrier to the long term investment goals of SWFs. This has led these funds to be major players in global infrastructure investment.

SWFs have also started moving away from publicly traded companies. Such mature companies are often also in mature markets, which tend to be somewhat cool with slow, steady growth. Recent market contraction, while very good for short term stock growth in these established companies, also only serves to cool those markets even more in the long term. In response, SWFs have been increasingly investing in unlisted companies, acting as venture capital. They have thus become major players in directing technological innovation.

The current state of SWFs is thus that state controlled investments play an outsized role in directing national development. With their influence over infrastructural and technological development increasing, SWFs already steer the direction of development to some degree. The initial design of these funds was strictly to avoid that steering. Fund managers see being tied up with policy-making as bad because it distracts from the goal of creating long term state wealth. But getting tangled with policy seems inevitable. Is the only way of preserving the long term focus of SWFs really to create such an iron curtain between policy and investment?

Developing countries have recently begun answering, “no” to that question. Rather than invest in foreign markets for financial returns, SWFs in some nations have begun focusing on domestic investments in key industries. As developing nations grow their economies, they have begun to find the transition from an industrial economy to a knowledge economy difficult and painful. In response, many have begun using their SWFs to invest in training citizens for more knowledge based jobs, domestic innovations, and domestic firms within the knowledge economy which need more access to capital in order to grow.

In such situations, SWFs balance their focus on long term financial growth for the fund, while also promoting domestic economic growth and steering domestic economic policy in line with the priorities of government officials. Given that such funds inevitably influence innovation and development anyway, why not do so intentionally in a way potentially in line with the democratic priorities of citizens?

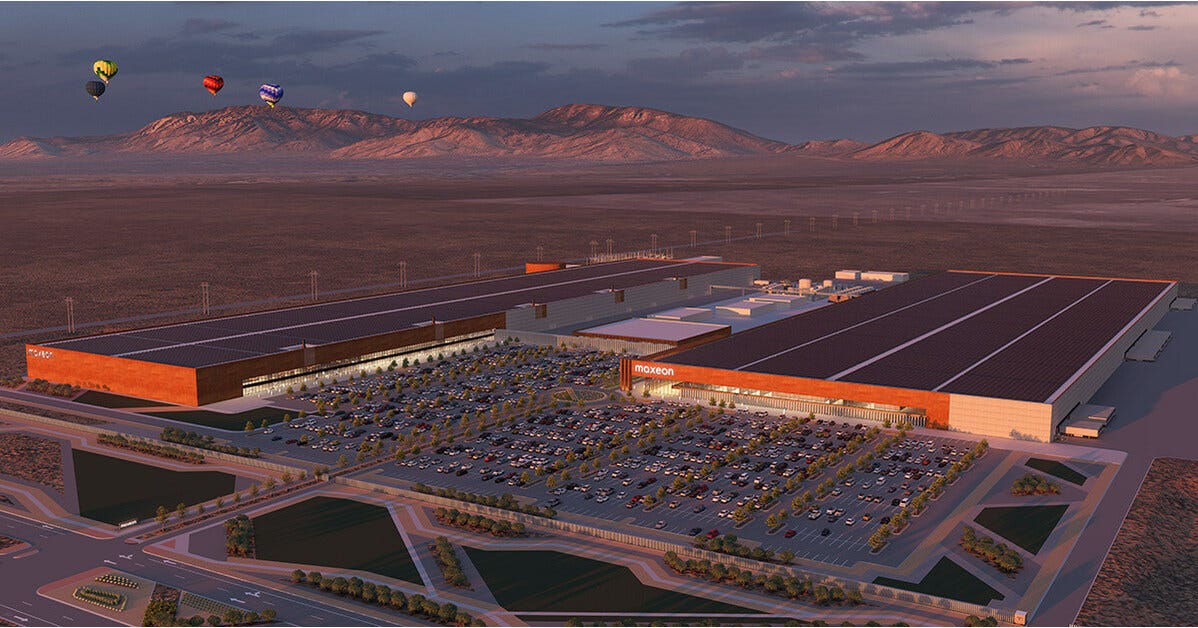

Since such funds are often funded by money from the extraction of natural resources, they could invest in companies that might diversify the local economy. This way they might shift away from reliance on natural resources. For example, New Mexico’s economy is largely dependent on oil extraction from the Permian Basin, the proceeds of which contribute to New Mexico’s four permanent funds. Together, these funds are managed by the State Investment Council (SIC) which forms New Mexico’s sovereign wealth fund. This fund already contributes to the state's policy goals, funding about 15% of the general fund annually. But the primary goal of the fund, like all SWFs, is long term growth. The state has recently been trying to attract renewable energy industries to try to wean off of fossil fuel extraction currently so important to the economy. Success has been mixed. For instance, Maxeon had planned to build a solar factory near Albuquerque that would represent nearly 1/10th of the U.S.’s total solar manufacturing capacity! But Maxeon’s recent financial troubles make the prospects of this factory tenuous. At $1B, it would cost more than the company is currently worth! But the SIC currently controls over $43B, and having doubled its value over the last five years! Substantial investment in either Maxeon, or their largest stakeholder, Chinese company TZE, could allow the company to build the factory, payoff financially in the long term, and both expand and diversify New Mexico’s economy.

SWFs already invest in innovation. But they could invest in innovations that are better for the citizens on whose behalf they invest. Today, these funds invest in companies like Uber or Alibaba. We’ve already covered what makes Uber so nasty. And how much benefit do most people really get from a Chinese Amazon? Instead of Uber, could such funds invest in public transit or high speed rail in cities and regions that are underserved? Instead of more cheap crap that people don’t need, what if funds invested in manufacturing processes that were safer for workers or less polluting? What if they invested in more environmentally friendly chemical processes? Or perhaps invested in cures or treatments for under-studied diseases?

Yes of course SWFs could do all this, but you may be wondering why bother with the middleman? Why invest in private sector businesses when we could just have state owned companies instead?

We’ll address state ownership more directly and in more detail later. But for now, SWFs have several potential advantages. Most prominently, the focus on growth and separation from policy-makers allows them to take a longer term view than state owned enterprises might. Consider a politician who wants to, for example, reform the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Such a reform might help people stuck in flood prone homes to move while also saving the government money from no longer having to pay to repeatedly rebuild flood prone properties. But in the short term, flood insurance premiums would almost certainly go up. Such a politician would have an uphill battle ahead of them, and risk losing their next election if they went forward with their reform plan. In a similar vein, state owned enterprises might be pulled towards short term goals. The long-term focus of SWFs provide a necessary balance.

Nor should we discount their goal of financial growth. State run enterprises tend to have worse financial performance than private enterprises. Where they don’t, this is usually because state owned firms get preferential regulatory treatment and access to insider information about government policies. But studies of Vietnamese firms indicate that domestic firms controlled by the Vietnamese SWF outperform both privately owned and state owned firms, despite the fact that they do not have the aforementioned advantages of state owned firms! Having a source of financial growth essential to the economic prosperity of citizens, especially for states reliant on temporary sources of wealth like trade surpluses or natural resources. So, being a tool that can balance that goal with the goal of directing capital towards innovations that meet more people’s needs more of the time is an advantage that SWFs have over state ownership.

Although sovereign wealth funds are, today, mostly just a tool for states to use to turn short term financial windfalls into long term financial growth, they also offer a unique opportunity to help steer development and innovation. Rather than steer it in the direction that the Elon Musks of the world want it to go, SWFs can instead steer it more democratically. SWFs have the unique benefit of being able to take a longer term approach to profits, allowing them to invest in innovations that might take too long to pay off for private investors. While traditional VCs have to balance the high risk of investing in new innovations with the potential of very large short term payouts, SWFs can balance those risks with steady benefits over a longer period. Despite not being as directly influenced by states and the needs of citizens as state owned businesses might, they are nonetheless still beholden to the needs of the state that owns them. But they also have the slack to be more responsive to those needs over long periods of time, and the ability to absorb short term financial risks to achieve their goals. We should consider that SWFs can do a lot more than we currently use them for!

This is just an astounding state of affairs for New Mexico. I had no idea. (I bet very few people do.)