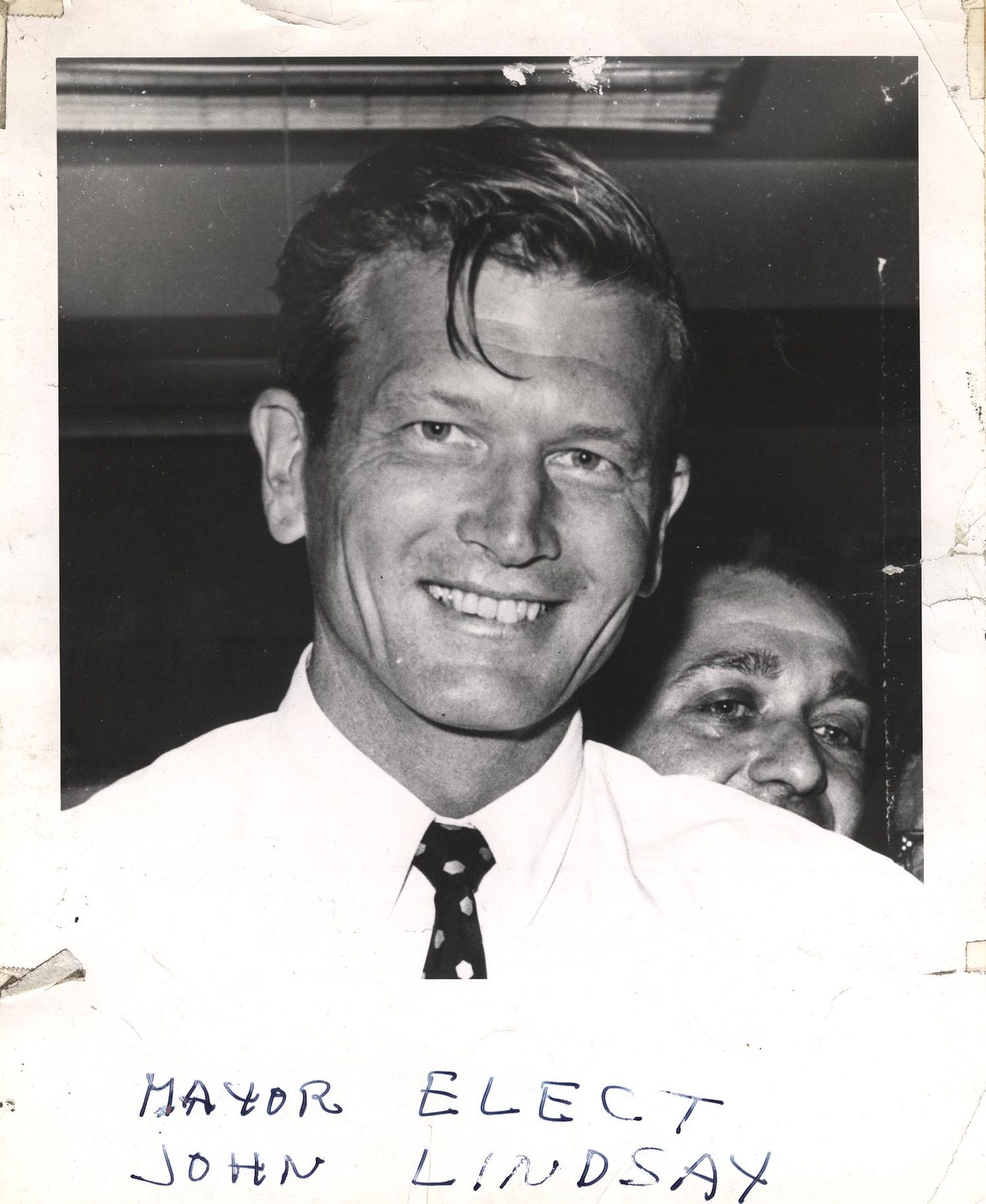

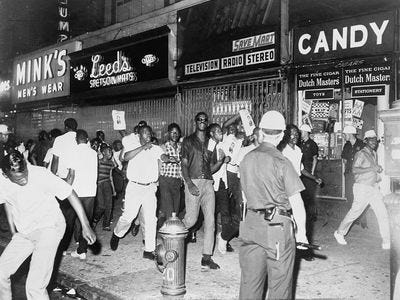

When John Lindsay became New York City’s mayor in 1965, the metropolis was in disarray. Much like other big American cities during that turbulent decade, NYC suffered from violent crime waves, tight budgets, and worsening racial tensions.

Although Lindsay was a Republican, he was actually more liberal than the Democratic candidate, something that seems hard to believe today. His administration made racial reconciliation a priority. One of the centerpieces of Lindsay’s plans was implementing civilian oversight of the even-then notorious NYPD.

The effort floundered. The civilian oversight panel was decisively rejected in a city-wide vote, and other programs were simply not workable. In the words of Charles Morris, the administration’s “soaring rhetoric…seems to have generated only confusion and hostility among front-line workers,” adding that “the programs had a strong tendency to emphasize symbol over content, to value structure and participation over program results.”

How little things have changed in the last 60 years. Morris’ words would seem to apply equally well to the Diversity, Equality, and Inclusion (DEI) efforts underway at many colleges, universities, and other large institutions—and for good reason. The common thread throughout decades of policy failure has been advocates’ indifference to on-the-ground application. Grand visions become fiascos when their designers neglect the people who are supposed to actually implement them.

Why Practitioners Matter

The failure to turn Lindsay’s proposed civilian review board into reality was partly a result of ineffectual politicking. The mayor believed that his proposal was already a reasonable compromise, consisting of a mixed board of both officers and civilians, with the latter holding a slim majority. However, rather than actually negotiate with conservative whites who worried more about violent crime than police brutality or with Black residents who felt the board didn’t go far enough, Lindsay simply jammed the proposal through. His attempts at persuasion took an existential, “there is no alternative” tone. Do this or suffer the looming race riots, he seemed to say, preemptively blaming the Police Benevolent Association for any future discord, “if there was a blow-up, they would be responsible.”

But Lindsay’s biggest mistake was not having front-line officers onboard. No doubt that some of them would have resisted any threat to their autonomy, but as Tamar Jacoby reported, “others were worried that the extra scrutiny would tie their hands in dangerous situations, endangering them and the people they were trying to help.”

Lindsay’s split with his police department was a microcosm of what sank his broader program, what historian Charles Morris described as “a massive effort at uplift, a final breaking-through of the barriers of oppression and discrimination that prolonged the abject misery of blacks and Hispanics.” Lindsay directed an array of city agencies toward this goal. Righting the racial wrongs of the past wouldn’t just be the responsibility of the police and welfare departments but also of parks and recreation, sanitation, housing, and local hospitals. At these agencies, the problem wasn’t outright opposition, like it was for the NYPD. Rather, front-line workers simply didn’t know how to implement, much less measure the success of what Lindsay’s administration appeared to demand from them.

Mayor Lindsay’s failed bid at racial reconciliation is cited in legal scholars Greg Berman and Aubrey Fox’s recent book, Gradual: The Case for Incremental Change in Radical Age. They use it to illustrate the “practitioner veto.”

All political changes depend on three things right: politics, policy, and practice. You might elect all the right people, design and pass seemingly perfect laws and regulations, but still fail to change the behavior of the people who actually turn that policy into reality. A grandiose new federal education program can crash and burn, because the selected curriculum doesn’t actually work or because new sticks and carrots present perverse incentives or motivate quality teachers to leave the profession. No policy can work without having on-the-ground practitioners on its side.

Reading a recent article in New York Magazine, I saw something like the practitioner veto at work in sinking DEI efforts at the University of Michigan (and elsewhere). The roots of DEI programs lie in John Lindsay’s era, but it wasn’t until the 2000s that diversity training became a widespread thing and that dedicated DEI offices started appearing at corporations and colleges. The peak arguably arrived only recently, with the waves of anti-police brutality protests during the pandemic and with diversity becoming the main lens through which journalists at major outlets analyzed current events.

Like Lindsay’s proposed police board, DEI efforts face criticism from both sides of the political aisle. Conservative provocateur Chris Rufo alleges that the growing role of DEI in university planning represents “the degeneration of universities into centers of ideological activism.” My far more leftwing colleagues roll their eyes when asked about their institutions’ DEI offices: They’re just empty symbolic efforts to brand the university as inclusive and avoid lawsuits.

At University of Michigan’s Ann Arbor campus, the ranks of DEI professionals have swollen by 70 percent. Job applicants are required to submit diversity statements, providing evidence of how they will support a diverse student body. Professors receive training on “antiracist pedagogy” and handouts that give tips for recognizing “White Supremacy Culture.”

However, enrollment of Black students at the campus remains lower than it was in the 1990s. And tensions between students and faculty only seemed to have increased, with even well-meaning efforts by instructors to admit their flaws and acknowledge their own struggles in trying to support diversity getting interpreted as “problematic” and “ignorant.” Then there are the burgeoning numbers of Title IX complaints.

DEI seems to have both failed to address persistent inequalities and, even worse, only further amplified social mistrust. There is a lot to unpack regarding why. But what immediately came to mind after reading through Berman and Fox’s book was the practitioner veto.

While small experiments will seem insignificant in the face of America’s persistent racial divisions, they are preferable to grandiose plans whose spectacular failures give the impression that no solution is workable

In my own experience, DEI has been a top-down, academic-driven effort. The framing has, almost without exception, been: “You, ignorant faculty, are the problem. Here, we will enlighten you.” However knowledgeable an invited DEI consultant or new Vice President might be, they usually aren’t experienced practitioners. However well researched a critical analysis of the structural racism of the neoliberal university might be, it doesn’t offer much guidance for a professor trying to help a minority student facing financial difficulties survive another semester.

Even worse, DEI efforts seem to have only ratcheted up the consequences for error. Missteps by faculty and staff bring student demands for administrative intervention. Practitioners live in fear of making, even honest, mistakes. What otherwise might be a simple misunderstanding or miscommunication can result in a formal hearing. One professor at Michigan faced administrative penalty for admitting to his students that he might need their help and feedback, should he unconsciously reinforce gender stereotypes in the classroom.

From Practitioners as Problems to Practitioners as Solutions

All political change is unavoidably incremental. Grandiose plans get compromised when practitioners either don’t know how to implement them or when they actively oppose them.

Often this is a good thing, such as when rank-and-file Washington bureaucrats refused to implement President Trump’s more extreme demands. When it comes to addressing persistent racial inequalities, we might lament the result of the practitioner veto, but it presence alerts us to an important reality: The proposed policy was too utopian. It literally had nowhere to land.

The take home lesson is that it is far better to be intentionally incremental. That way, one chooses when, where, and how small steps are taken, rather than have that decision be made for you by the randomness of circumstance.

Grand plans at University of Michigan were compromised by being torn between the demands of Title IX legislation, of an increasingly “woke” student body, and of administrative bean counting. A former dean described it as all “a good show”, as “jumping through hoops” to give others “what they wanted to see.” But “no one knew what they were supposed to be doing.” Reports were written. Posters were printed out. Training sessions were given. But did it actually help students? DEI advocates wanted programs that made a difference. Instead, we got ones that look good in terms of metrics that probably don’t matter.

My hope is that efforts to help students from diverse backgrounds feel a greater sense of inclusion at America’s colleges and universities can get back on track. In order to do so, they’ll need to start where the institutes’ practitioners are at, supporting and encouraging them to devise and experiment with new strategies, and using more punitive strategies only as a last resort. While small experiments will seem insignificant in the face of America’s persistent racial divisions, they are preferable to grandiose plans whose spectacular failures give the impression that no solution is workable. The question, however, is whether we are capable of the patience and grace that such an approach requires.