While it is easy to find paeans to democracy, most people view bureaucracy as, at most, a necessary evil. And some see it in even more dismal terms. Eugene McCarthy argued that “an efficient bureaucracy is the greatest threat to liberty." Theater critic Brooks Atkinson wrote that, “as soon as a bureaucracy is established, it develops an autonomous spiritual life and comes to regard the public as its enemy."

The image government bean counters busily creating the forms and procedures that at once execute the law as they insulate the public from the machineries of governance strikes us as being outside of democracy, even if political administration is an indispensable part of modern government. Democracy is supposed to be responsive to the public interest, or, more accurately, the momentary confluence of public sentiments.

Bureaucracy, on the other hand, is technocratic. It is designed to be responsive to internal rules, the letter of the law, and administrative expertise. And it is purposefully shielded from the prevailing political winds, as its authority is supposed to derive from rationality and technical know-how, not popular legitimation.

In liberal political theory, the seemingly paradoxical relationship between the two modes of governance is exactly what sustains democratic societies. The federal bureaucracy acts like an informal fourth branch of government. The fact that career bureaucrats can refuse orders, or at least slow-walk them, amounts to a “practitioner veto” to an executive that is overstepping their bounds.

Indeed, President Trump was unable to enact many of his preferred policies during his first term simply because a cabinet member refused to carry it out and/or because bureaucrats made sure it didn’t happen. His interior secretary complained, “There’s too many ways … for someone who doesn’t want to get (a regulatory action) done to put it in a holding pattern.” How-to bureaucratic resistance guides were published in the Washington Post and elsewhere.

Evidence from abroad provides additional support for the liberal democratic appreciation of an independent bureaucracy. In Hungary, Orban has used the country’s regulatory system to crush media organizations that publish unfavorable views of his government. Even if bureaucracies operate undemocratically, in the liberal democratic view, they nevertheless help ensure the sustainability of democracy by decentralizing power.

But, then again, it isn’t hard to find examples of bureaucracies being dedicated to doing the exact opposite of what voters want, and for decades. As Ruy Teixeira pointed out as the Trump administration was gutting USAID, foreign aid is unpopular among a majority of Americans.

But the more important examples consist in the trade, banking, and countless other regulatory systems, that many Americans see as built to serve the elite. In the words of Yascha Mounk, many scholars argue that “rich individuals and big corporations favor trade treaties, independent central banks, and powerful bureaucratic agencies because they can capture the professionals who work for these institutions, bending their work until it furthers the interests of the wealthy and powerful. In short, most members of the political class favor technocracy because its opaque institutional apparatus makes it easier for them to ignore the popular will.”

I believe that there is a way out of this dilemma. And part of the answer is recognizing that thinkers from Max Weber onward have been fundamentally wrong about what bureaucracy is capable of doing, and as a result have failed to imagine what it could achieve.

In a 1986 article, political economist Charles Lindblom argued that political analysts who thought they pursued the public interest were chasing a chimera.

What I am proposing, then, is not that we neglect the public interest, but that we recognize that our versions of it are,-partisan, and that we give up any pretense of appearance of speaking from Olympus, or as neutrals, or as representing a nonpartisan integration of interests that is for the good of all and injurious to none.

We either lack the ability to find solutions that are in the interests of the entire public, or, more frequently, such a solution doesn’t exist. And politics is less about knowing the answer and more a collective commitment or choice to harm some for the benefit of others.

Much the same is true for bureaucrats. They invariably serve some partisan vision of the public interest, often one that was thought up decades ago and now has become entrenched and unassailable. One thinks of the mountain of bureaucratic red tape that had made it all but impossible to build anything other than a single family home in America for generations.

The rosy image, at least within liberal political theory, of bureaucracy as a means to safeguard democracy belies the problem that it often does so by having transformed one particular political group’s vision of the public good into a ostensibly “rational” criteria for bureaucratic decision making.

To take another example from urban planning, many of the choices made in designing public roads have little basis in rigorous science. As a result, transportation engineering doesn’t do enough to prevent people from needlessly dying on city streets, and instead works to lock us into the current transportation system.

While it is tempting to believe that we might right these sorts of wrongs over time. Perhaps we might figure out how to get the *right* experts at the helm of different bureaucracies, that they might figure out and implement road designs and economic policies that objectively fulfill the public interest, I’m with Charles Lindblom. The belief that bureaucracy could ever root its authority in objective rationality was always pure fantasy.

The alternative, having to recognize that bureaucracy is inevitably politically partisan, isn’t something that we have to lament. Rather, acknowledging the reality of biased and limited expert bureaucratic opinion is freeing, for it enables us to reimagine ways of doing government such that democracy and bureaucracy are no longer binary opposites. If government experts and administrators can no longer reasonably see themselves as separate from politics, or as capable of an unbiased vision of how laws ought to be executed, then they are forced reach out to the public.

Once we dispense the pretense of neutrality, the best that bureaucrats can hope to achieve is a thoughtful and honest form of partisanship. That is, we are not destined for a world in which bureaucracies are weaponized by polarized governments. In contrast, I think that thoughtfully partisan/democratic bureaucracies could be the answer to much of what politically ails countries like the United States.

A promising exemplar is the Toxics Use Reduction Act passed by Massachusetts in 1989. During the decades in which federal toxic chemical regulation has been a chronic failure, in which tens of thousands of chemicals were left unevaluated and the EPA’s actions burdened by fanatical opposition from the chemical industry, Massachusetts has slowly detoxified many of its businesses. Its Toxics Use Reduction Institute (TURI) provides expert guidance to help firms eliminate dangerous chemicals from its production processes.

While federal-level bureaucrats were tasked with the impossible task of discerning the risk level at which a chemical run afoul of “the public interest,” their peers in Massachusetts acted as thoughtful partisans for a less toxic world. Rather than expect to discover a rational or harmonious consensus on chemical risk, they hammered out compromise solutions with business owners. As Charles Lindblom would have put it, TURI scientists create the conditions for collective action where they did not previously exist. It is a model for democratic bureaucracy writ large.

What a thoughtfully partisan central bank might look like is beyond my expertise on economic systems, but I hope that someone is thinking about it. I’ll end with an example of where the idea’s application to other areas of governance is a little more obvious.

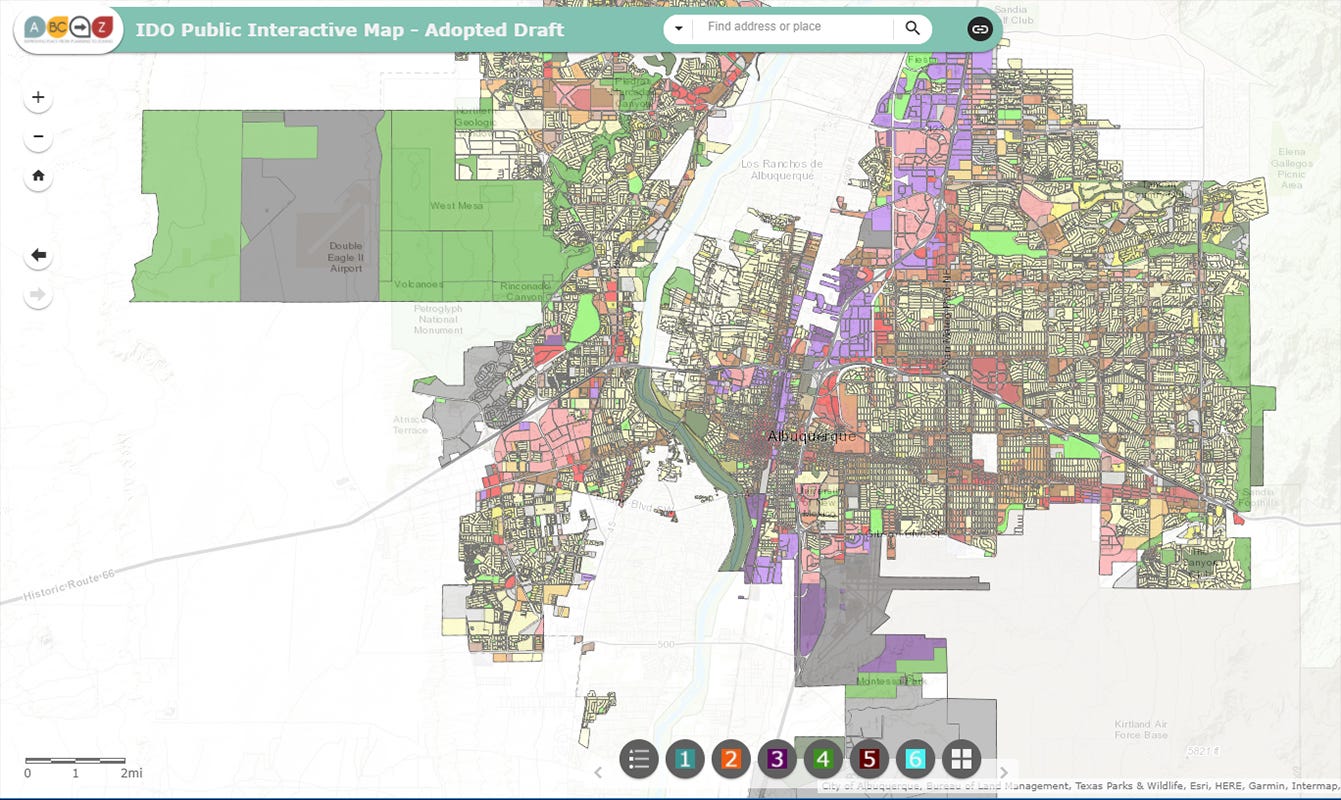

The current polarized struggle between NIMBYs and YIMBYs is the outcome of land use planning long being isolated from public engagement, and the fact that what little public input that does happen occurs at public hearings filled with angry senior citizens.

YIMBY calls to solve the housing affordability crisis by restricting land use decisions to state-level bureaucrats are mistaken. They’re rooted in the technocratic dream, steeped in the idea that there’s “one right” answer to how cities should be constructed and failing to consider that future state bureaucrats might actually arrive at “rational” solutions that YIMBYs won’t like.

I try to imagine how the situation might unfold if land use planners’ understanding of the terrain of public disagreement was as detailed and nuanced as their zoning maps. If they saw their jobs as not mechanically applying urban space regulations nor as discerning the urban public interest, they could dedicate themselves to figuring out which areas of the cities could support what kinds of collective action. To act thoughtfully in the YIMBY version of the public interest would be to discern the neighborhoods with the strongest positive constituencies, the places that can serve as test beds, and (one hopes) exemplars that could prove that what passed for zoning common sense during the 20th century was at least partly misguided.

We might come to see the relationship between democracy and bureaucracy as akin to that between science and technology. As Daniel Sarewitz and Steve Rayner pointed out, technology is “is what makes science real for us.” Bureaucracy needed not be an institution that either sits aloof from or acts antagonistically against democracy. Instead, it could make popular rule feel more “real.” And, in the process, we might unleash the latent intelligence lying within modern democracies and better direct it toward solving public problems.

"We might come to see the relationship between democracy and bureaucracy as akin to that between science and technology."

Honestly, I'm not sure things are going so great on that front these days.