Can We Reverse America's Democratic Decline?

Wrestling with the complexity of the 2024 election crisis

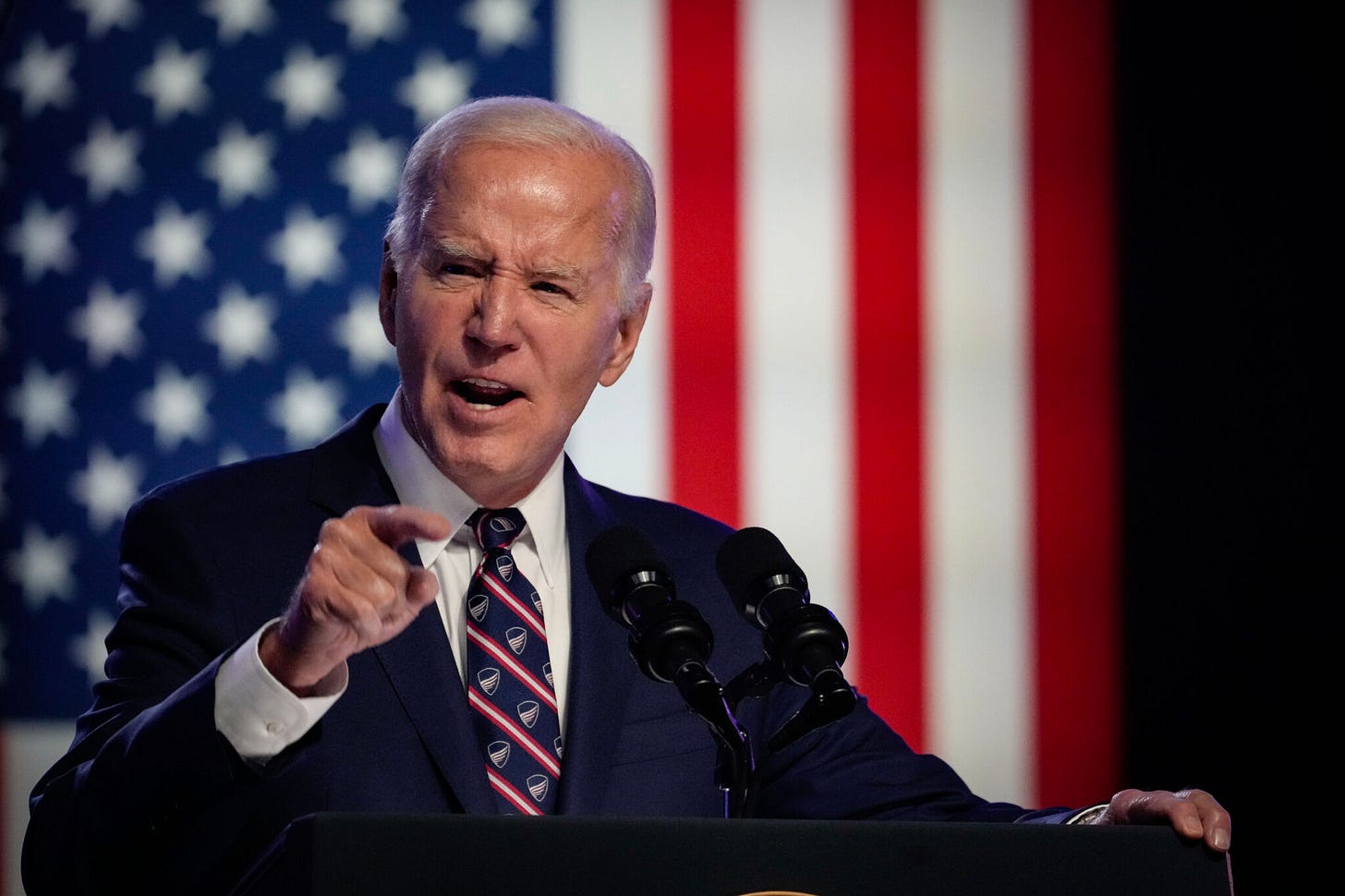

On January 5th, President Biden officially launched his reelection bid, and he came out swinging against former President Trump. Biden warned that the likely Republican candidate was “willing to sacrifice our democracy, [to] put himself power.” And the president depicted January 6th as the “day that we nearly lost America, lost it all.”

We don’t typically comment on Washington politics at Taming Complexity, partly because we don’t want readers to think of this as a liberal or a conservative blog. Our focus is on better decision making, on how people can work together to make better choices, regardless of their political orientation. But, given the stakes of the 2024 election, it seems irresponsible to not talk about how we might better grapple with the complexity of America’s current political crisis.

Many people on the left, including president Biden, are worried what a second Trump presidency will bring. No doubt that much of the original controversy over the former president had more to do with his demeanor and language seeming “unpresidential” to liberals. But Trump’s final days in office signaled that he wasn’t just an unconventional executive with a flair for abrasive language. He spent these weeks desperately trying to hold onto power, making claims about electoral fraud that even Fox News producers (in private) described as outlandish.

Yet the story of Trumps final months also depicts the resilience of America’s political institutions. Secretaries of State across the country, including conservative ones, refused to play ball when asked to select electors contrary to the popular vote. And Vice-President Pence rebuffed Trump’s efforts to get him to refuse to certify the election. Even as a groups of citizens agitated (some violently) outside and within Congress, power nevertheless transferred to President Biden.

The “nearly lost America” narrative has motivated efforts to keep Trump off the ballot. Colorado’s highest court recently decided that the former president’s actions on January 6th met the insurrection cause of the 14th amendment. The 4-3 split decision, among seven Democratic appointments, signals that the case isn’t exactly black and white. The applicability of a Civil War-era constitutional change to a semi-spontaneous mob is self-evident primarily to partisan true believers. Trump’s words that day, while by most accounts irresponsible, left room for plausible deniability.

Advocates of the decision insist on the need to define clear boundaries, to set a precedent for acceptable behavior for presidential candidates. This defense isn’t really about democracy per se. Rather, it stems from the philosophically liberal idea of merit, the belief that a representative republic should be governed by the wisest and most level-headed among us. From this perspective, executives need the right qualities, in order to help safeguard the office from potential demagogues and the impassioned masses that support them.

In any case, conservatives fall back on the second story of Trump’s presidency, pointing out that America’s institutions held firm. From this, not totally unreasonable, viewpoint, it is Democrats’ efforts to keep Trump off the ballot that are instead the threat to democracy. They are exaggerating the risks of a second Trump term for political gain. And that, unfortunately, feeds into the probable Republican presidential candidate’s already apocalyptic rhetoric.

There is a legitimate worry that the 14th amendment will be invoked more regularly to disqualify candidates for ever more trivial reasons, only further undermining trust in the electoral process. Most importantly, despite hundreds of articles, news segments, and opinion pieces, average Americans and even law professors remain divided over what January 6th really meant.

What is clear is that American politics is reaching a breaking point. Fear that “the other side” will extinguish our democracy shifts us away from the normal politicking of the past. The stakes become existential. The country itself is ostensibly at risk. And in such situations, people crave certainty. They want to believe that someone is at the controls and can restore the order to a situation that feels increasingly chaotic, whether it is the firm hand of a president who seems to yearn to be a strongman leader or through the judiciary’s interventions.

Neither of these answers, however, address the underlying drivers of American political upheaval. Misuse of executive power will on only further polarize Americans. And Court decisions in Colorado and elsewhere seemed to have solidified conservative support behind the former president. And this, in turn, only increases the level of panic among the left.

Tragically, Trump never had a real chance to win most of these states, and most observers predict that the Supreme Court will overturn state-level decisions anyway. A few symbolic court victories have only further entrenched the crisis.

What we need to do is get at the core of America’s current political woes: Populism. Many citizens believe that “the people” are not being adequately represented, that elites are imposing their will. Contemporary American populism is driven by the belief that credentialed experts behind many political decisions are actually working for special interest groups, not trying to meet the public’s demands.

The 2010s Tea Party movement was itself a response to the perceived aloofness of mainstream conservativism, that Bush-style Republicans cared more what policy wonks thought about immigration and other issues than the concerns of their political base. Today’s Trumpism draws its power, in part, in reaction to the technocratic tendencies of contemporary Democrats. As the left increasingly depicts itself as the party of expertise and science, conservatives are evermore worried that “the facts” is a rhetorical ruse to unilaterally implement liberal policies.

We can see this in the growing educational divide between Democrats and Republicans. Prior to 2004 there was little partisan split between people with and without a college degree. The vast majority of people with a Bachelors degree now vote Democrat. Unsurprisingly left-wing political rhetoric more and more sounds like a college class lecture, less responding to voters’ divergent demands and more aiming to “educate” them of the right policies. The shift was visible already under President Obama, who blamed political disagreement on citizens being “just misinformed.” He claimed that if the president provided them with “good information”, then “they will make good decisions.”

Reactionary populism and aloof technocracy forms a negative feedback loop, which is why the left’s current response to a Trump candidacy has only further animated right wing support. When journalists like Margaret Sullivan insist that journalists no longer cover the election as a “horserace” but solely in terms of “Trump’s threats to democracy,” she forgets that doing doesn’t persuade many conservative voters but instead leads them to believe that newspapers have become a mouthpiece for the Biden government. When an untested and esoteric constitutional section gets used to take Trump off the ballot, skeptical citizens perceive it as unfair interference in the electoral process.

Because populism is characterized by extreme mistrust of journalists, politicians, judges and experts, it can’t be solved by those groups unilaterally deciding what’s right (or even true). That leads citizens to feel evermore alienated from the political process. It worsens public animosity. Populism is like political quicksand, where the more we try to pull ourselves out of a polarized quagmire by brute expert force only sinks us deeper into the morass.

There are no quick fixes. Partisan resentments built up over the course of decades can’t be easily reversed. Achieving a more normal and less pathological democracy means de-polarizing politics. Congressional gridlock and the dismissive, unproductive political rhetoric dominating social media (and increasingly journalism) can only be escaped if citizens’ can once again learn to see each other as reasonable human beings, who can legitimately disagree without being seen as misinformed, corrupt, or brainwashed. Unless Biden (or other political leaders) can persuasively talk about citizens on “the other side” as anything other than a threat to democracy or deplorables, our political culture will continue its downward spiral.

Reversing the decline requires that governments be more responsive to a broader range of citizens. For issues like immigration or the war in Gaza, the Biden administration is increasingly out of step with voters. More than that, the president’s honest efforts to bridge the “diploma divide” hasn’t been enough to reverse working class resentments that have built up since the 2008 Wall Street bailout.

The reason for this, as Justin Vassallo has pointed out, is that a preoccupation with exclusionary academic-activist jargon and identarian culture waring leaves non-college graduates feeling left behind by liberal politics, that leftists have little respect for them or they way of life.

No doubt that Republicans have their part to play as well, especially in finding a way to respond to populist resentments that, unlike Trumpism, doesn’t just further erode trust in politics. And, as the last two Speakers of the House have tried to do, they need to step back from a reliance on fanatical political maneuvers. But their efforts would be aided by Democrats more often extending olive branches to conservatives looking to chart a less polarized political path. Instead leftists have actively (and cynically) amplified far-right candidates, running the risk of further destabilizing Congress in order to win a few more races each election cycle.

I fear that the 2024 election could be a turning point for the United States, a high water mark in political dysfunction. Polarization increases people’s willingness to erode political norms to keep the enemies of the “other side” out of power. And polarization is only amplified when politics takes on an existential tone. Ultimately, our problems have far deeper and more complex roots than the mere presidency of Donald Trump. I only hope that more of us can begin to recognize that reality.

Yes, but the Democrat party should first be legally barred from holding any official government office for its treasonous activity from 2016-2023.

Yes we can. We need to build new systems that make the old ones obsolete. They must be corruption resistant, transparent, decentralized, and thus trustworthy.

Humans need a place to go where ideas can percolate. That used to be Congress but it has become too corrupted.

We fix it all with a brand new entity. A non profit network state run in a way that is super hard to corrupt:

https://youtu.be/gqbSZcbu8lI?si=3AkNDP1AYE_JiOKX