Doomsday Birthquake?

Don't treat population decline like an apocalypse.

Just because it's possible to avoid population collapse doesn’t mean it will happen automatically. Nor does it mean that doing so will be painless. Even if the population rates do level off, it may still be difficult, for example, to find enough caregivers for an older population. Avoiding collapse won’t mean much to me if I’m alone and isolated except for my elder care robot! What can we do to ensure we avoid the worst case scenario, and even to improve our outlook?

The problem with population decline is that it isn’t just one problem. In reality, it is a series of complex interrelated problems. This makes it difficult to address head on. It would be nice if there was one policy or type of policy that could be a panacea for population decline, but it is becoming increasingly clear that there is not.

Consider Garvey’s analysis of Japan’s demographic crisis. The declining birth rate sits at the confluence of cultural upheaval, collectivist social expectations, and economic collapse. If Japanese lawmakers could wave a magic wand and fix their economy tomorrow, it still would not alleviate the crushing social pressure supporting one’s family. Likewise if all men there suddenly became ideal citizens, it wouldn’t change the economic ability to live up to those intentions.

Or compare the US to many European nations. Europe boasts fewer working hours, more holidays and paid vacation, and generous parental (thats right, for the father too) leave policies. Since many child-free Americans cite having to choose between having a family and career success, surely these countries that provide ample room for family rearing must be staving off declining birth rates? But no, fertility rates throughout Europe are lower than in the U.S. Another oft cited reason for avoiding parenthood is economic anxiety. But the relatively strong American economy hasn’t protected us from declining birth rates either. So, then, what is to be done?

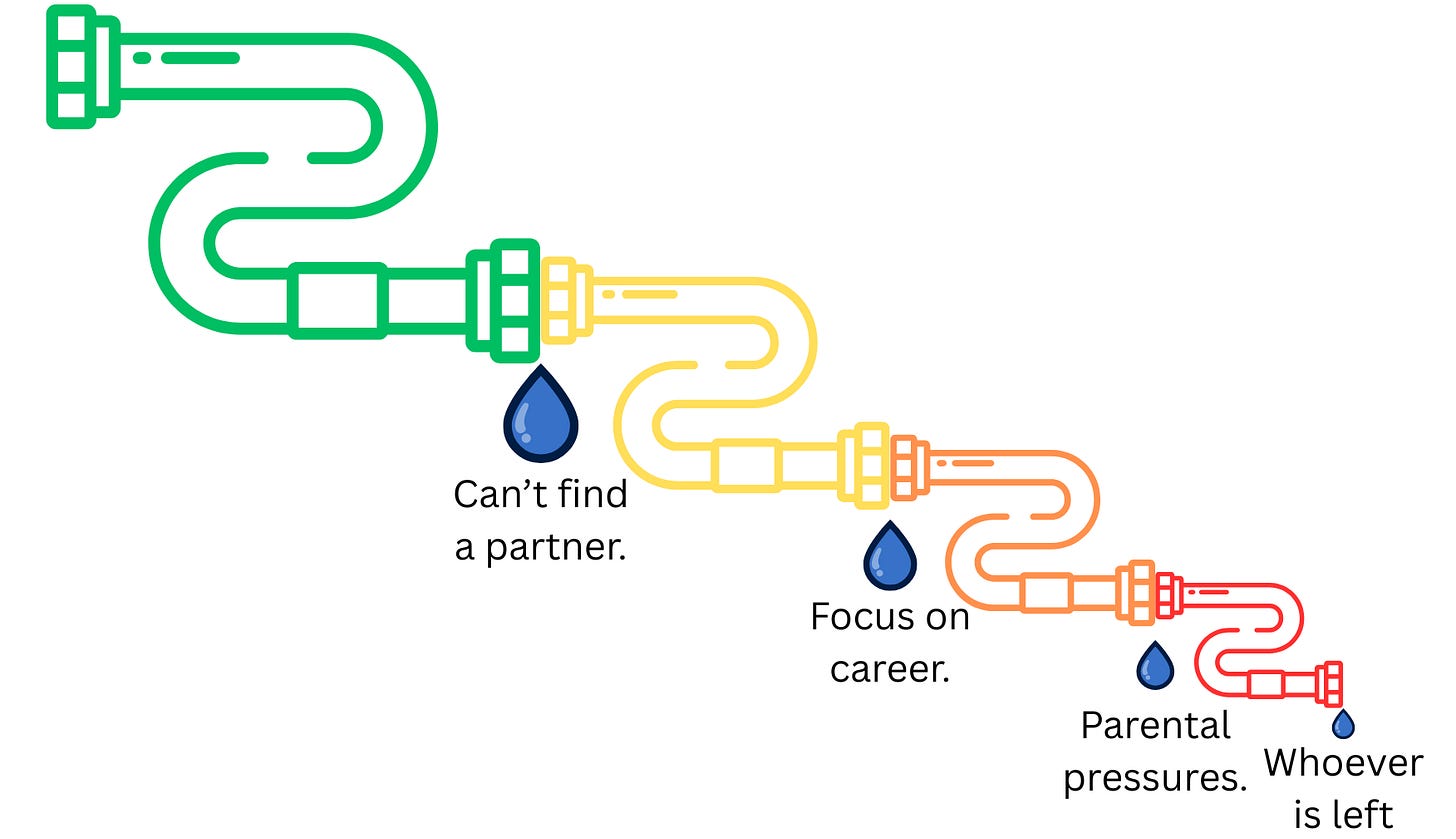

We might view raising a family as a pipeline. At various points along the way, people who might otherwise have kids or have more kids “leak” out of the pipeline. A prospective parent may not be able to find a partner to raise kids with. If they do, they may not see raising children as feasible or desirable. Even if they did, they may choose to have only one kid so they can focus their energies on providing the best possible life for them, rather than take on the seemingly unmanageable task of meeting escalating parental expectations for a second child. Even if they want to have more than one kid, they may have started their family later in life and simply run out of time before having as many children as they wanted. Potential parents leak out of the child rearing pipeline at all sorts of points for a variety of reasons, and no one policy is going to patch every hole.

To have kids, first you need a romantic relationship. It takes two to tango. But romantic relationships are more difficult now than it was when my partner and I started dating in 2009. There could be numerous causes, and it is very difficult to distinguish which ones, if any, are the most impactful. In most developed countries, dating apps have become the primary way that people find partners. But these apps operate on a somewhat transactional basis, meaning that people finding partners on these apps must act more transactional as well, even while lamenting that very same change in relationships! Starting in the 80s and 90s, divorce rates in most developed nations increased substantially. Although this rate is now decreasing, it's possible that widespread divorce among the parents of those currently in the dating pool led to more risk averse dating styles. Whether it's frustration over transactional relationships or not wanting to repeat the mistakes of their parents, increasing numbers of young people de-prioritize romantic relationships rather than continue to slog through bad first date after bad first date on the off chance you don’t get ghosted. There are other sources of fulfillment to be had.

Even if you do meet someone, there are many reasons why one might not want to have children. Garvey and Dotson both discuss how important it is to live in a society that people want to bring children into. Child free couples around the world have cited issues like climate change, economic anxiety, and career advancement. But as both my colleagues have already so eloquently discussed, these issues are less the root cause, and more the outcomes of social features that can be anti-parent. Whether it's because they want to focus on careers, or because they don’t think they can afford it, successfully coupling up doesn’t guarantee a desire for children.

Even if a couple wants children, they might have fewer children later in life than they would prefer. I didn’t finish grad school until I was 32. Even if I had had children right away, I would have still been nearly five years later than the average age of a first child in the U.S. And my situation is becoming less and less divergent. In the 1970s, the average age of a first child was 20, almost unimaginable today when most jobs require degrees that keep people in school until at least 22. Advanced degrees, both masters and PhDs, are far more common as well. And as educational attainment in the workforce gets more and more common, job seekers have to spend more time trying to make themselves stand out. All of this leads to people starting their careers later in their lives. In turn, they start families later in their lives as well, if at all.

Without a doubt, there are numerous other reasons why people have fewer or no children. It isn’t feminism, or birth control, or the economy. None of these are sufficient for explaining all of the reasons people aren’t having kids. Anyone telling you what *the* cause is, is trying to sell you something (often herbal supplements). But at least we can hold on to hope if we believe the demographic crisis has a singular cause and, therefore, a singular solution. Otherwise how does one deal with such a thorny, interwoven mess?

The problem is that population decline is so complex that it is nearly impossible to implement a single, comprehensive reform. We simply can’t understand the problem well enough to get it right! When analysis fails you, the only way forward is to muddle your way through. At least, that's what political scientist Charles Lindblom argues.

To muddle through something means to make manageable, bite-sized changes and then reflect and see how those changes worked. This kind of intelligent trial and error is a tailor made tool for attacking problems with too many unknowns to make comprehensive reform.

We’ve discussed this concept before when examining Danish wind turbines. Part of the reason Danish farm-tool manufacturers succeeded where NASA engineers did not is because they made small changes to well known designs, learning what worked and what didn’t, while slowly scaling up the production of their turbines. NASA, on the other hand, quickly made massive wind turbines based on mathematical theory that proved unreliable in real world conditions.

Trial and error learning is, inevitably, going to be riddled with failures. South Korea spent $200M over 16 years offering financial incentives to have babies and have one of the world’s lowest fertility rates. China has rolled back abortion access in the country, also to no avail. And liberal parental leave policies throughout the EU have not spared the continent from a precipitous drop in birth rates. Nobody knows what kinds of policies are going to work. The key is being both willing and prepared to learn from mistakes.

That's the real problem with apocalyptic thinking: it leaves no room for learning from errors. As Dotson has discussed in multiple articles, apocalyptic thinking stifles disagreement and undermines incremental improvement.

Apocalypses are tough to be in. They don’t leave a lot of time to act and the repercussions of doing the wrong thing are literally existential. These two factors make for bad decision-making. Extreme consequences can justify excluding people you think are wrong (after all, if they get their way we’re all going to die!) and the immediacy of the situation doesn’t leave time to experiment with different strategies. And when both factors combine, the proposed solutions are, inevitably, massive in scale.

Take, for example, pro-nuclear environmentalists who oppose innovative reactor designs because the impending doom of climate change leaves no time to explore alternatives to light water reactors. Under normal circumstances, it seems plainly foolish to plunge blindly forward into a single technology for energy production for the foreseeable future. But when framed against the existential risk of climate change, suddenly otherwise reasonable people believe there is no other way.

Prophecies of apocalypse reduce complex politics into stories of moral certainty. When the Meadows’ describe degrowth as the solution to the environmental harms of over consumption, they are responding to the facts no more than they are their experience along the hippie trail. Yet in doing so they portray their opponents as villains who will destroy us all along with the planet. It's their way or the highway. To disagree is to invite the predicted apocalypse, and who but a villain or a fool would do that?

Pronatalists do much the same. It's not enough that single cat ladies merely have different values, they must be part of some plot to undermine western cultures (whatever that is). Why else would someone knowingly walk us closer to the edge of population collapse?!

But what is their alternative? Jordan Peterson has suggested that the problem is women’s access to education. Although he pragmatically suggests that it probably isn’t possible to deny women educational opportunities, the subtext makes his preferred solution clear. Idaho Republican Senator Chuck Winder has suggested that the problem is abortion access. At Natal Con in 2023 (yes, it is a thing), Charles Haywood argued that women should not be in the workforce and that the civil rights act, by protecting against sex discrimination, has been one of the most destructive American laws ever.

It’s pretty clear where the movement is going. And most reasonable people, if asked, would probably disagree that rolling back women’s rights by a hundred years is the correct response. But the fear of apocalypse can make people support positions they otherwise might not. Malcolm and Simone Collins, two of the most outspoken pronatalists, claim to think Haywood’s position is dumb. But they have no problem supporting the Natal Con. And their own positions seem merely to be more vague than Haywood’s, blaming “wokeness” on declining birth rates rather than directly calling out women’s rights.

When we start to see population decline and demographic collapse as an impending apocalypse, we will likely find ourselves in one of three scenarios. We could encounter a vicious cycle of doomerism where it all feels too futile to do anything about. Disagreement could turn into a political morass (like bears in Idaho). Or the worst possible option, the pronatalists get their way, lead sweeping changes to the very concept of equality under the law, make women’s lives worse for at least a generation (among who knows what other unanticipated consequences), all while still not stopping demographic collapse.

Despite having no children myself, I share Garvey’s concern about how we will take care of our aging population. But when I think about why I or any of my childless friends haven’t done our share of increasing the population, the reasons don’t seem nearly as one dimensional as any discussion I’ve yet read would make it seem. I know people who forgo having a child for numerous reasons: child care, career aspirations, financial stress, lifestyle preferences, not feeling or being prepared for parenthood, and the list goes on and on. There is no single policy that can address all of the causes at once.

The issue of population/demographic collapse requires policy experimentation and learning to solve. Apocalyptic rhetoric and thinking, on the other hand, will only make those solutions harder to achieve.