Germany has a few unique institutions, because of, well, history. One of them is called the Bundesamt für Verfassungsgschutz (BfV), which translates to the “Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution.” It’s basically a domestic intelligence agency tasked with identifying internal enemies to Germany’s constitutional order. This last week the agency classified the country’s increasingly popular Alternativ für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany or AfD) party as “extremist,” opening the door for the new government coalition to potentially ban it.

Even if incoming chancellor Christian Merz declines, the classification permits the BfV to increase its surveillance of the party. They can now recruit informants and spy on the party’s internal communication.

For a little less than half of Germany’s citizens, a ban seems to be self-evidently correct. Reading comments and skimming social media, it isn’t hard to find sentiments to the effect that Merz just needs to grow a pair and do what’s right. Just as I said about similar efforts to prevent Donald Trump from running for present, however, I think the moment to act has long passed. And I’m not sure if banning a party is ever the right strategy.

AfD’s extremist label is justified by a 1000 page report. My German isn’t good enough to skim something that long in any conceivable timeframe (I don’t even know if native speakers can manage that).

From what I’ve looked at, the BfV points to several pieces of evidence. A number of AfD members have made public statements that argue that recent Muslim immigrants are culturally incompatible with their own idea of what it means to be ethnically German. One proposal tied to the party, called “Remigration,” even calls to deport insufficiently assimilated migrants, potentially even ones with a German passport. And they have argued against what they see as a culture of “hereditary guilt” over Nazi Germany’s horrific deeds during World War II, with some figures, like Björn Höcke, being fined for using Nazi-era slogans.

Are the statements and positions of several leading politicians enough to damn a whole party? One way the BfV tries to justify this is by pointing to social media likes and friendship networks. The most extreme segment of the party is called “der Flügel”, and the agency found that, for what it’s worth, a large percentage of AfD members have a connection to it. That’s something but not totally definitive, which is probably why the AfD has filed a lawsuit against the BfV.

A full ban, in any case, requires a lot more than just extremism or the support of policies that might get declared unconstitutional. The party must be attempting “an active campaign against the free democratic order…to overcome the political system.” As I understand it, the AfD would have to pose a clear and demonstrable threat to basic democratic institutions, like the electoral system or the checks on parliamentary government’s power. And that’s, once again, a up for interpretation.

The opposing parties have all disavowed the AfD and refused to work with it, which has yet to harm the party’s electoral fortunes. It also has deprived them of evidence regarding what its leaders would actually do should they gain power at the federal level, which ironically may have only made their legal battle against the AfD harder.

Earlier efforts to ban the more extreme National Democratic Party (NPD) faltered, because the party remained far too small to be influential, to be a serious threat. Another attempt went sideways when it was learned that 15 percent of the party’s leadership were actually on the intelligence agency’s payroll.

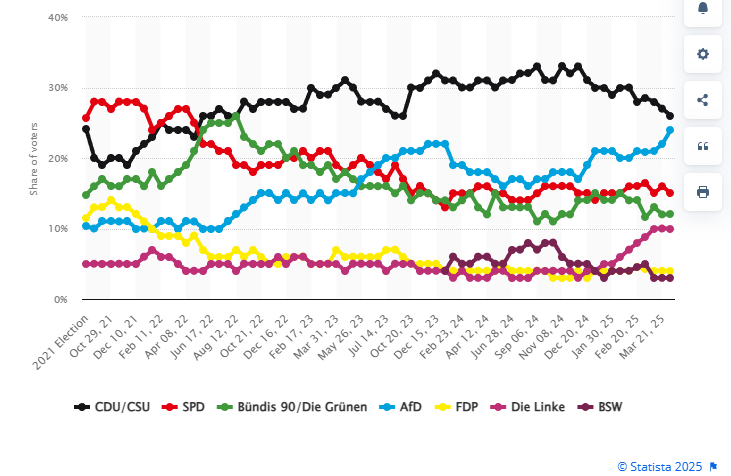

That’s not the case for the AfD. The problem is that the party now has *too much* support. It’s currently polling first, above the Christian Democrats, with a quarter of voters. As such, the German approach to political extremism has actually a laid a trap for the country to step into. It might make sense to ignore small parties, since it seems like more work than its worth to ban them. Yet, waiting until they have broad support, and hence pose a chance of winning power, puts the government in the position of having to alienate a big chunk of the electorate, who (rightly or wrongly) see the party as representing their interests.

This trap was set by the idea of “defensive democracy,” which blinded German officials to its presence. Defensive democracy grows out of the concept of liberal guardianship. It is the idea that rights need protected from democracy, usually by a class of knowledgeable experts, such as the Supreme Court or a domestic intelligence agency. The trouble is that liberal guardianship is itself non-democratic. Its victories can be pyrrhic, protecting the constitutional state from presumed threat only at the cost of undermining the perceived democratic legitimacy of that very state.

It seems to me that this is where the approach to the AfD is faltering. Certain policy questions have essentially become “verboten,” because straying from the previous mainline consensus puts one dangerously close to AfD policy positions. Opponent politicians have tried to delegitimate the party by excluding it. The grievances and resentments underlying popular support for the party are, in turn, also waived away as illegitimate. It would be unconstitutional and human rights violation to accept fewer refugees from Syria or Afghanistan, noted a government spokesperson back in August.

Yet, that hasn’t stopped Denmark’s left-wing government from implementing a stricter immigration regime. One Danish policy requires that immigrants shake the hand of a city council member, which is meant to weed out people whose religious beliefs won’t let them shake the hand of someone of the opposite sex. Seeing progressive gender beliefs collide with the traditional left position on lax borders should, I think, give one pause. It signals that the issue of immigration isn’t as straightforward as we think, that there might actually be legitimate alternatives to yesterdays seeming political consensus. It shows us that immigration is too complicated and crisscrossed with conflicting values to be adjudicated by lawyers in front of judges—rather than debated within parliaments.

Just as I argued prior to Donald Trump’s reelection, right-wing populism won’t be defeated by legal maneuvers and court-room arguments. Citizens support populists when they believe that governments no longer care what they think, when they believe that experts and other elites only say they are for democracy but actually govern for their own benefit. The question for the German government is if they really think that they can ban the AfD without inadvertently seeming to verify those beliefs. If they can’t, they risk the possibility that something far more extreme will rise from the AfD’s ashes.