Limits to Public Engagement

The Failure of the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM)

Asteroids are pretty interesting but you probably don’t think too much about them in your everyday life. Most people don’t. But when it came to the Asteroid Redirect Mission, or ARM, NASA thought that everyday people like you and me should get a bigger say in setting mission goals and priorities.

Though we don’t often think about it, asteroids do sometimes impact Earth with destructive force, and I’m not just talking about the dinosaurs. In 1908, an asteroid approximately 50-60 meters in diameter exploded 5-10 km above the Tunguska River in Siberia. The air burst annihilated over 2000 square km of forest, felling 80 million trees. Luckily, the area was almost completely uninhabited, and eye witness reports from the time suggest perhaps only three people lost their lives.

But asteroids don’t always fall over uninhabited regions of Siberia. In 2013, a much smaller asteroid, only 18 meters in diameter, exploded over Chebarkul, a city of about 40,000 in the southern Russian region of Chelyabink Oblast. Nearly 1500 people were injured, mostly by flying shards of glass from the shock wave, and buildings in six cities across the region were damaged. In this case, we were lucky that, even though the area was populated, the asteroid was small enough that no one was killed.

But in 2024, it looked like that luck might run out. A Chilean telescope observed an asteroid about the same size as the Tunguska impactor that would cross Earth’s orbit. Initially, scientists calculated the probability it would impact the Earth at over 3%. Fortunately, as they continued to track its movement and could gain a more accurate prediction of its trajectory, that likelihood went down to 0% (although it still has a 4% chance to impact the moon, which might look pretty spectacular).

An extinction level impact event is so unlikely that we can take our time protecting ourselves from it. We probably have around 35 million years to get ready, since they happen about once every 100 million years. But a mass casualty impact event is probably worth preparing for. The ARM would have helped build up the technological capability to do just that.

The initial design for the ARM had three main stages:

Detecting, characterizing, and selecting a target for the mission from among near Earth asteroids.

Redirecting the target asteroid into lunar orbit.

Sending crewed spacecraft to the asteroid to explore and return samples.

These three stages reflect four main priorities.

First, redirecting the asteroid is practice for defending against a potential asteroid impact. It would sure be nice to know we’ve successfully redirected an asteroid *before* a city is on the line.

Second, study and sample return reflect the priority of scientific study. Asteroids are often leftover material from the formation of the solar system. They never got incorporated into planets or moons and therefore never subjected to all the active processes of those bodies. In a sense, they remain preserved. So scientists who study them can learn a lot about the formation of the solar system that they cannot learn from elsewhere.

Third, sending astronauts to the asteroid adds to the prestige and publicity of the mission. Strictly speaking, sending a human crew is not necessary to either of the above goals, and only adds to the risk and expense of the mission. But there is a real sense among many space policy makers that human space exploration has suffered since the end of Apollo. Moreover, many also believe that this lull in human exploration provides an opening which other nations can capitalize on to make the U.S. look dull and complacent. Human spaceflight can act as a proxy for which country is the most technologically preeminent.

Fourth, sending astronauts to a pre-prepared destination is a relatively easy step on the way to Mars. NASA’s Moon to Mars architecture takes an incremental approach to get to Mars. Starting with developing a launch vehicle capable of leaving Earth’s orbit, NASA plans to conduct progressively more difficult missions, further from home, until eventually sending astronauts to Mars. The ARM was to be situated within that progression as a test for long distance space travel before landing on the Moon.

But what really makes the ARM unique is two-fold. First, it was the first mission to include a participatory technology assessment. Scholars from Arizona State University designed two public forums, one in Phoenix and one in Boston, where citizens of all backgrounds could discuss the goals of the mission and set priorities. The goal was to incorporate public values into the mission design process. The second thing that makes ARM unique is that Congress took the unusual step of explicitly excluding ARM from the 2018 funding bill. While Congress often increases or decreases NASA funding, and may even work to dictate the general direction and focus of the agency, they do not usually earmark or prohibit funding on a mission by mission basis.

We’ve written before about how important public participation is to successful technology programs. It builds trust and legitimacy which often leads to public support. So what happened? Did Congress undemocratically step in to cancel an otherwise popular mission? Did public participation not actually do any of the things we claim it does? Why was ARM such a dramatic political failure despite NASA’s efforts towards better public engagement?

By all accounts, the design of the ARM’s participatory technology assessment firmly rooted itself in the most recent studies on public engagement and deliberation.

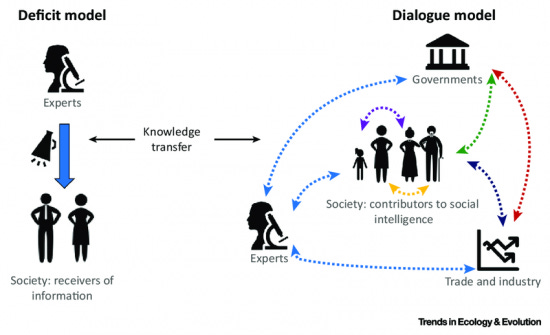

The exercise as a whole pursues public engagement and participation rather than public outreach; a dialogue rather than a lecture. Far too often interactions between experts and members of the public follow what is called the deficit model. This model posits that the public has a deficit of knowledge, and the job of experts is to fill that deficit. In the context of government science programs, such as the ARM, the usual thinking is that the public will support science if only they understand it enough. This is why educational campaigns are so common as a strategy for gaining public support. But the ARM didn’t fall into that trap. This was not a mere educational campaign, instead it was NASA officials that would learn about public preferences. The views expressed by participants would inform NASA’s decision making about ARM.

The forums were two day events that began with presentations by experts to provide participants with a common background about relevant topics. These briefings were designed to be as similar as possible to the sorts of briefings NASA leadership would receive. Participation in the forum was deliberative. Participants engaged in open discussion with their peers with trained facilitators. This oriented the forum toward going beyond merely capturing opinions to capturing the values and priorities that underlie them. It also increased the level of participation such that nearly all participants contributed directly to discussion. The participants were also diverse. The makeup of each forum reflected the demographic makeup of the state where it took place across multiple categories: gender, age, education, ethnicity, income, and employment status. The deliverables of the forum focused on usable outcomes. It was not just data for NASA leaders to use, but actionable items. Forum organizers wrote reports summarizing the conclusions of the participants. They also conducted surveys before, during, and after deliberations about key decisions NASA would have to make about the ARM. By all accounts, the forum organizers were very diligent and thorough in their design to facilitate the best possible integration into decision making.

So what was missing then?

In the next installment, I’ll talk about the many answers to that question. If you’re familiar with our previous writings about intelligent trial and error, you can probably guess some of the things I’m going to touch on.