Merchants of Despair

Why political rationalism fails to solve environmental problems

Another day and yet another promising environmental law has been blocked by unscrupulous industry lobbying. Sound familiar? That’s the narrative being told about the “Sustainable use of plant products” proposal being rejected in the European Union Parliament Plenary. And it’s the story told every time something like this happens, whether for gas stoves or plastic pollution: Business interests have too much influence, and they are “sowing doubt” by denying the science and blocking unquestionably good laws. Please do despair as environmental progress falters.

The pesticide proposal was a radical one. It would have demanded drastic cuts in agricultural pesticide use. Drafters recommended “50% reduction targets [as] legally biding at [the] EU level.”

I think the story being told about the “Sustainable use of plant products” is wrong. Coverage of environmental policy should do more than repeat the argument from Merchants of Doubt ad nauseum, because the narrative of “business denying the science” grossly simplifies the politics involved. Even more, it doesn’t motivate smart political strategizing that might actually break policy gridlock.

Values Become “Facts”

The “industry denial stops environmental progress” story has many parts. But it ultimately depends on the existence of a scientific consensus that we are all in grave danger. A Desmog article on the struggles to implement pesticide reduction starkly presents the stakes involved: “a livable future.”

That argument hinges on the threat that reduced pollinator biodiversity has on agriculture, a risk remains highly uncertain. In a recent article, a set of scientists noted that “there is still a lack of basic information about how [pollinator] species diversity…contributes to seed and fruit yield and quality in most crops.”[i]

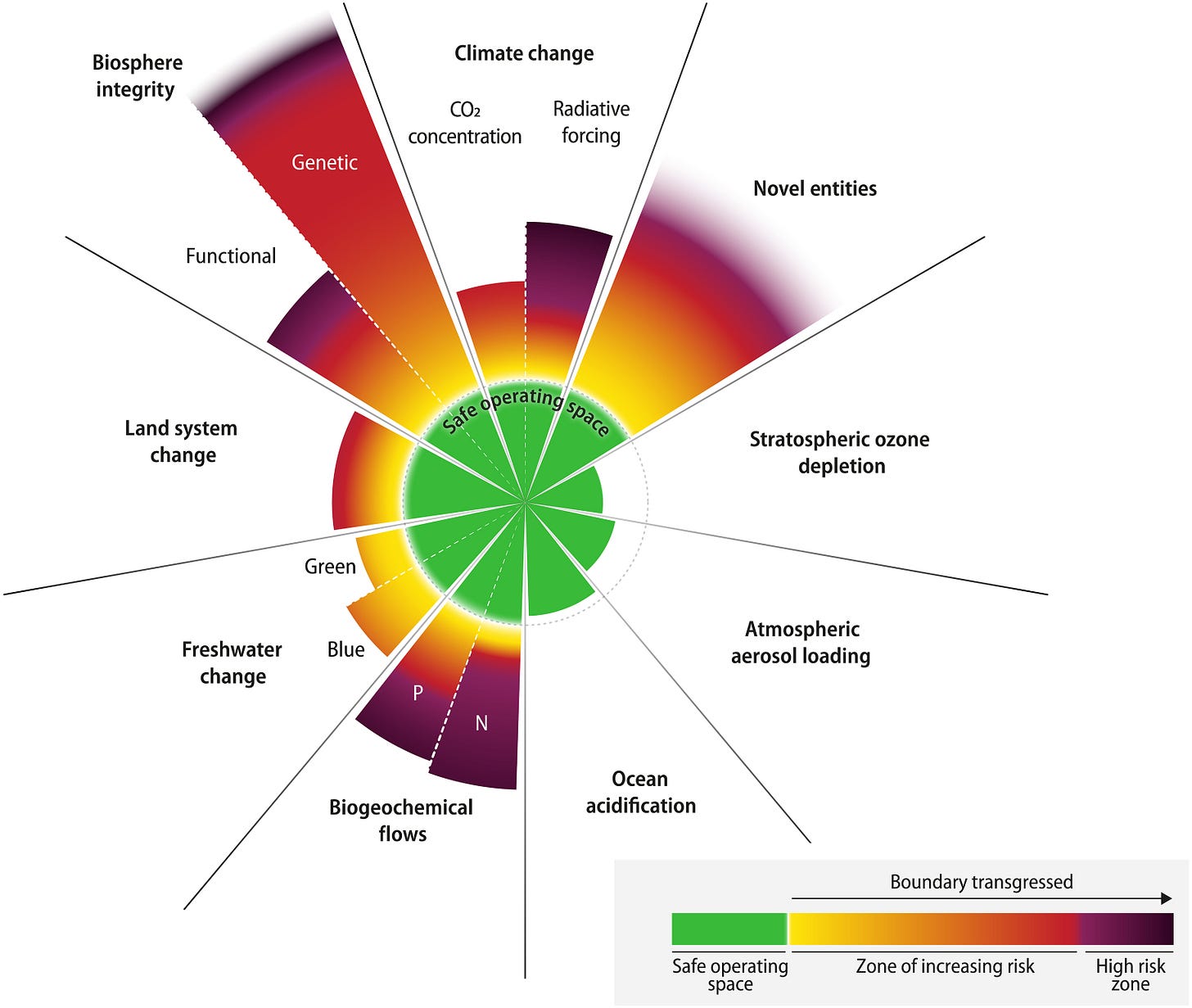

Whether something a 50% reduction in pesticides is desperately needed in the short-term, despite the existing uncertainties, depends quite a lot on value-laden assumptions. It relies on the presumption that nature is fragile and intrinsically imperiled by human chemical creations. Indeed, one article on topic uncritically cites the theory that humans are exceeding knowable and well-definable “planetary boundaries.” But scientists are really not in agreement about this presentation of humanity’s environmental challenges.

As policy scholar Steve Rayner pointed out, presenting contemporary pesticide use as surpassing an “non-negotiable threshold” depends on weighing tradeoffs between the value of biodiversity and of the benefits of agricultural technology. But these value judgements are obscured when they are presented as “facts of nature,” a presentation that “shut[s] down debate.”

Industry, unsurprisingly, responds with its own tales of potential calamity: high prices, reduced food security. The standard “merchants of doubt” narrative warns that these claims come from industry studies, likely to be biased by profit seeking motives.

Yet, environmental scientists have their own potential sources of bias. They mostly come from a narrow segment of the population: white, middle to upper class, highly educated parents, non-religious, and skeptical of capitalism and economic growth. University scientists come from a place where it is relatively easy to see harms to agri-business as an acceptable cost, or believe that organic or agriecological techniques can unproblematically transform farming.

To point that out is not to vindicate industry research. Rather, it is to understand that “science” can’t make our decision easy for us, no matter how much we try to wring dismal predictions out of it. We weigh uncertain studies about food prices and yields against equally tentative ecological science in light of our views about nature, the kinds of risks we are willing to tolerate, and what matters most to us.

Whither Environmental Democracy?

Whatever the potential benefits for biodiversity, demanding a fifty percent reduction in pesticide use is asking for a massive concession from industry, one that they weren’t likely to take lying down.

It reminds me of laws that set arbitrary end dates to the end of gasoline and diesel vehicles, purposefully set up in ignorance of whether or not EVs will be adequate and affordable at such a time. While you can argue that necessity is the mother of invention, trying to subject industry to such high-stakes uncertainty often motivates them to try to kill legislation. Seeing a gaping hole in sales within a decade probably looked like an existential risk to the pesticide business.

It is fine to lament the seemingly outsized influence of business, that 80 percent of the Expert Group on EU Food Security is made up of industry reps. On the one hand they probably have the most relevant expertise. On the other hand, a fairer arrangement would have a big place for potential critics of agriculture industry’s claims.

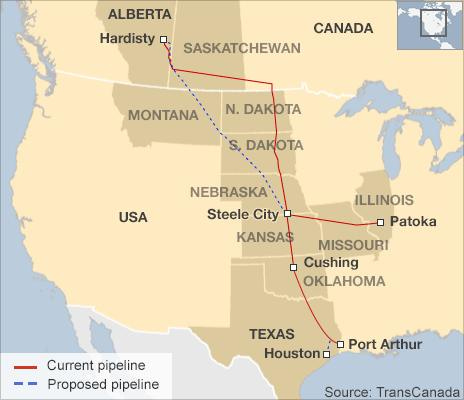

Given that we know that industry will have an outsized influence, the persistence of target setting, bans, and other seemingly radical environmental proposals is perplexing. The cynic in me wonders if what matters to environmentalists is less the solving of the challenges facing nature than visibly striking a blow against industry, or looking like martyrs valiantly succumbing in a battle against corporate capitalism. I’m reminded of the immense political capital spent to kill the Keystone XL pipeline, a project killed by the Obama administration even when its own state department admitted that the impact on carbon emissions would be negligible.

But that’s probably not a charitable reading. Really, the issue is that environmentalists tend to be political “rationalists” rather than “meliorists.” Rationalists’ seeming obtuseness when it comes to political conflict reflects their steadfast belief that disputes are settled by being “right.” The “correct” policy ought to be implemented almost automatically, full stop. They see coming to imperfect, and often contradictory, compromises with opponents as selling out the truth. It is no wonder that environmental rationalists yearn for global institutions that can dictate how nations must act to protect nature.

Merliorists contend that progress is typically (and often ideally) incremental. Because opponents can slow down or kill legislation, if motivated enough, partisan groups must invariably make concessions. For most environmental issues, that means compromising with business, not just demanding high-stakes cuts and prohibitions.

What’s so frustrating about the “merchant of doubt” narrative is that few success stories have involved directly challenging industry expertise and threatening their business. Tobacco might be the only example where political rationalism won the day. Attempts to ban toxic chemicals in the US have faltered for decades under the expectation that we need only “speak truth to power” to eliminate useful and profitable substances.

It is easy to feel despair, as the “science says cut/ban” approach repeatedly fails. But there have been successes, and they tell a different story.

The phase out of CFCs was begun before the science solidified, because large chemical companies saw a first-mover advantage in developing CFC alternatives. Likewise, progress in climate change has largely come from making renewables cheaper than fossil fuels (and, one hopes, EVs eventually cheaper than gas-powered cars).

We’ve made most progress wherever we can get industry partly on board, rather than demand that it sacrifice its business for the planet. No doubt that “the economy” unfairly dominates the discussion, that business interests probably concede far less than they should. But at this point, it is hard to comprehend the unwillingness incorporate industry interests in political strategizing as anything less than the abject failure of political rationalism.

From Despair to Progress

After 13 odd years observing and writing about science and technology politics, I’ve become a steadfast meliorist. I also feel that way in light of my commitment to democracy. The insistence that “the correct” solution must be implemented, hell or high water, leads the way to technocratic governance.

Industry has the right to lobby and advocate for its interests regardless of what a group of scientists say. And it’s still correct in the case of pesticides, because environmentalists may be wrong. Food prices and food security might be threatened, if the transition isn’t intelligently managed. Organic techniques might fail to deliver, if expected to too rapidly replace half of European food production.

But political meliorism isn’t about giving up on progress. It is to recognize that innumerable small steps are preferable to radical jumps, that getting opponents partly on board makes for more intelligent policy. I personally think that reducing pesticide use is a desirable goal. And if environmentalists proceed differently, we probably could dramatically cut the usage of agriculture chemicals relatively soon.

No doubt that environmentalists are correct to recognize calls for more research on the harms of pesticides to be a delaying tactic. What isn’t a delaying tactic, however, is explicitly funding research to make alternatives to pesticides cheaper, more effective, and easier to implement. Doing so lowers the stakes, making it easier for current industry to incorporate organic techniques into their portfolio, or by helping to build a countervailing industry with the opposite interests. Indeed, now that they have established electric models and built up their supply chains, automakers have come out for a ban on the sale of gasoline-powered vehicles.

Focusing first on better funding R&D on alternatives also frees us from having to undeniably prove the harm of pesticides. If the substitutes are made more feasible, then we can justify abandoning today’s pesticides simply because they are hazardous. Like for CFCs or incandescent bulbs, a ban could eventually be relatively straightforward to implement, but only after the available science, technology, and infrastructure lowers the stakes of doing so.

This might seem to make too many concessions to industry, to be insufficiently radical in light of the potential urgency of the environmental problem. But I think that is the wrong interpretation. What we don’t have time for is radical policies that either can’t pass or will be undone later by their unintended consequences. In the last few years, the Dutch were forced to implement stark nitrogen regulations, which brought protests and famers’ suicides. A populist farmer’s party then won the country’s provincial and senate elections. Far-right Dutch politician Geert Wilders’ recent electoral success probably has as much to do with his promise to reverse the nitrogen reduction laws as the rest of his platform.

The future of environmental progress is incremental.

[i] Simon G. Potts et al., “Global Pollinator Declines: Trends, Impacts and Drivers,” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 26, no. 6 (2010): 345-353.

You state "Far too much environmentalism relies on another kind of despair: Apocalyptic visions of environmental destruction. Planetary boundaries are a case in point." I believe the work of climate scientist Dr. Johan Rockstrom on planetary boundaries and Earth's tipping points is based on solid research. Rockstrom's work is a strong argument for urgent climate action, to cut our global greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% by 2030. Do you have any evidence to invalidate Rockstrom's research?

What strikes me as odd about this piece is that it buys into the “industry” idea and leaves out farmers. These are human beings, not corporations. Leaving out key voters and ignoring their lived experience seems like a problem in developing political consensus. Also there are substantial numbers of ag scientists who often aren’t asked about their views. What this does, at least in the US, is leave out farmers, ranchers, and their academic support network (ag scientists with the land grant institutions) from public discourse with the claim that “we know best”.. we being some academics and NGO’s .. and “what you know doesn’t matter.” A good way to sow division instead of food plants. IMHO.