Radical Incrementalism

What Albuquerque Zoning Changes Teach Us About Making Big Changes

Albuquerque, like many other American cities, is in a housing crisis. Housing costs are increasing at a rate that far outpaces income and the city has, until recently, done next to nothing to try to increase the housing stock. I’ve discussed this issue before on Taming Complexity, but it also contributes to other social issues that people also care about. Homelessness, for example, increased in the city by 13.8% between 2021 and 2022, and a whopping 83% between 2022 and 2023! To put it simply, Albuquerque just doesn’t have enough homes for its current residents, much less for a city that continues to grow.

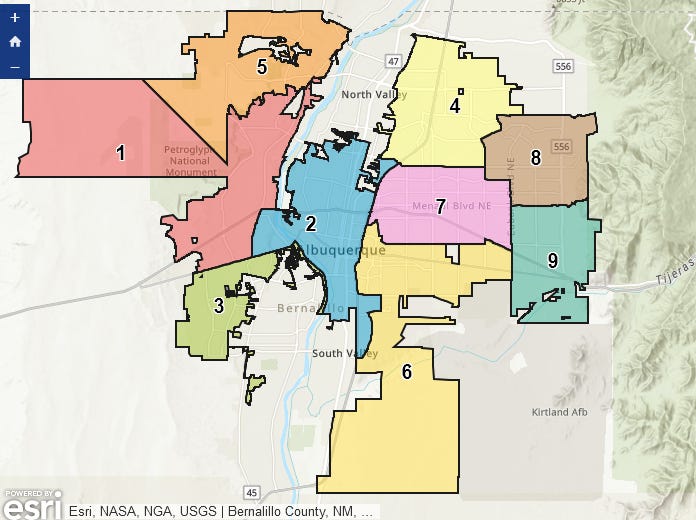

It would be easy to fix this problem if the city could sprawl out like so many of its peers. There are a myriad of reasons why that is undesirable, but it would at least alleviate the consequences of housing shortages that I’ve outlined above. But alas, Albuquerque has sprawled all that it can. To the East, the Sandia mountains present an inhospitable terrain for new housing. Plus most of the land is owned by the Forest Service, so cannot be developed anyway. To the West the Petroglyph National Monument blocks new housing development. The land to the North and South belongs to the Sandia and Isleta Pueblo respectively. While these two nations can of course build housing on their own land, the city of Albuquerque cannot. Albuquerque has nowhere to go but up.

Yet the city council has been very reluctant to make the necessary changes to city building ordinances to allow for denser development in the city.

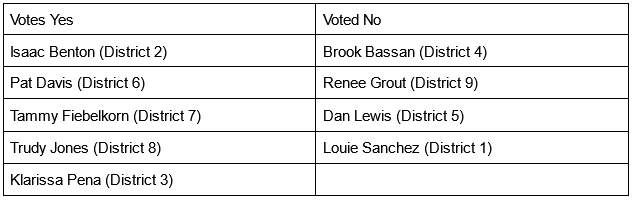

On June 21, 2023, the Albuquerque city council passed an amendment to the city’s Integrated Development Ordinance, or IDO, which is the city’s zoning code. The amendment allowed casitas, known elsewhere as accessory dwelling units (ADUs) permissively in all R1, or single family zoning. Though better than nothing, merely allowing casitas is a drop in the bucket compared to the city’s housing needs. But the amendment was originally much more comprehensive. As counselor Tammy Fiebelkorn originally proposed it, the amendment would have also permissively allowed duplexes in single family zones, reduced parking requirements for multi-family homes, and allowed developers to get height bonuses when building multi-family housing. Piece by piece, these parts of the amendment were stripped away. Even with all of these concessions, the amendment still only barely passed by a 5-4 vote. Even that was uncertain. It looked as if the amendment would only pass if casitas were zoned conditionally, until councilor Trudy Jones flipped her vote. After a long fought (over seven month!) political battle, the only thing the council could pass was a zoning amendment that would have no statistically noticeable impact on the city’s housing shortage.

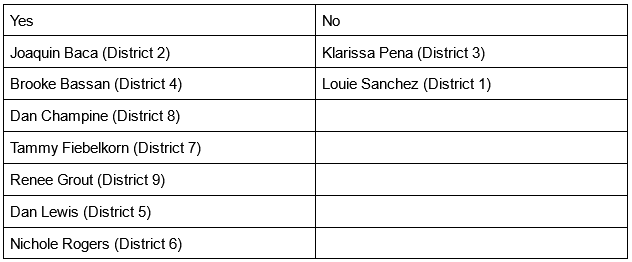

Nearly a year later, on June 17, 2024 Albuquerque city council again failed to amend the IDO to ease the housing crisis in the city. I’ve written about this amendment before. But to recap, originally proposed in December of 2024, this amendment returned to the goal of allowing more duplexes to increase density. This amendment offered a compromise on the previously nixed idea to allow duplexes permissively in all single family zones. Instead it instituted several limitations. First, duplexes would only be permissively allowed within ¼ mile of a transit corridor or commerce center. Second, duplexes would only be permissive if converting an existing property. Building duplexes on an empty lot or tearing down an existing house to build a duplex would only be allowed conditionally. Third, a property with a casita could not be converted into a duplex and vice versa.

The strategy was this: reflect on why opponents protested the previous amendment and write a new one that compromised with them over their concerns. It was a commendable strategy. Rarely do we see politicians making an explicit effort to learn from past mistakes, and it is genuinely laudable to see politicians also make a genuine attempt to alleviate opponents’ concerns through compromise. NIMBYs were concerned about the potential to suddenly and drastically change their quiet suburban neighborhoods. There would be lots of new people and potentially double the parking demand! So the amendment limited the geographic area it would impact to include only those areas with good transit so new residents wouldn’t need to bring cars and where those neighborhoods were already near dense and bustling parts of the city. They were worried about developers taking control of their neighborhoods and changing its character. So the amendment focused on conversions which are mostly only financially feasible for existing residents to do and would be nearly invisible from the outside, leaving homes looking the same. But it turns out opponents didn’t want these sorts of direct compromises. Their opposition wasn’t on the technical merits of the amendment. It was based on ideas and values.

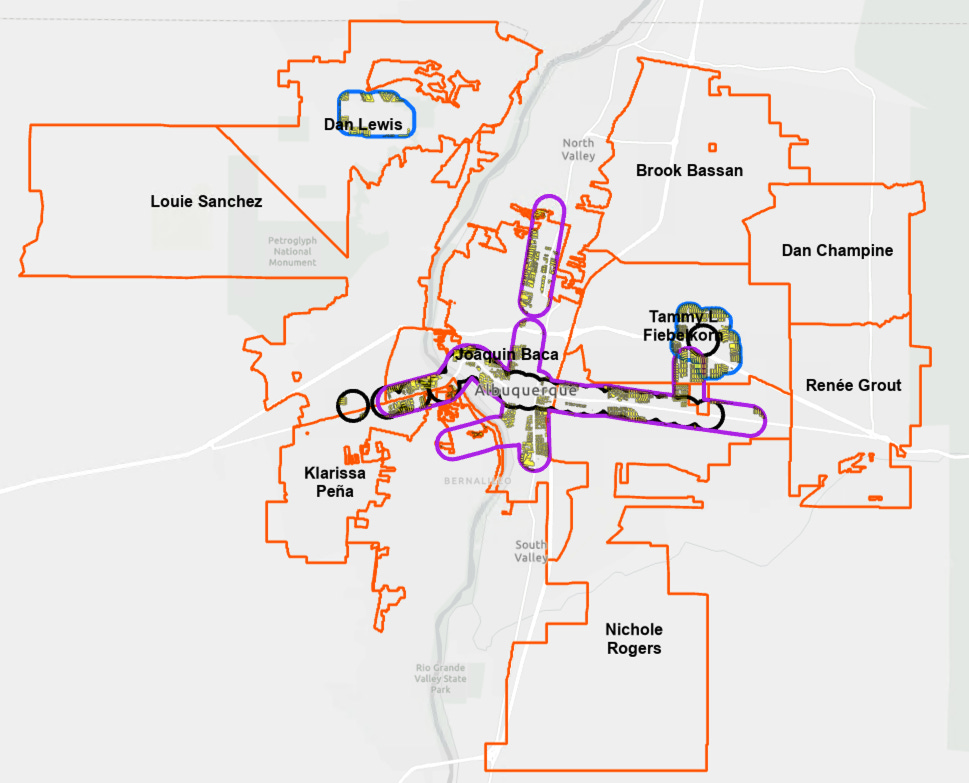

But then, on January 28, 2025, the city council passed an IDO amendment far more comprehensive than before less than a month after it was introduced. Beside direct changes to city zoning, the amendment also made it much more difficult to oppose developments that are only conditionally zoned. One especially large obstacle to such developments were the city’s Neighborhood Associations. These associations are not like Home Owners Associations. They don’t have any legal authority over their neighborhoods. They are purely political entities that are meant to advocate for the interests of their residents in political matters. In Albuquerque they are extremely influential in city politics, often being directly solicited for their opinions by the Mayor and Council members. They are notorious for opposing conditional developments. However, with this amendment, they would now have to submit a petition signed by the majority of property owners and tenants within 660 feet of the development. In other words, now they have to prove that they represent their residents, rather than merely claim that they do.

The zoning changes are equally as radical. The amendment didn’t just stop at duplexes. Duplexes, townhomes, and multifamily housing (like low-rise apartments) permissively in all residential zones. The geographical area is still limited, being only within ¼ mile of urban centers, main streets, and premium transit areas. But within those areas, the amendment also eliminates height restrictions, and reduces the parking requirements for these denser developments by 50%, or 60% if near an ART stop. Granted, there are still limitations, like limits to height differences for adjacent properties. But nonetheless it is clear that this amendment is far more comprehensive than any of the previous attempts to change Albuquerque’s zoning laws!

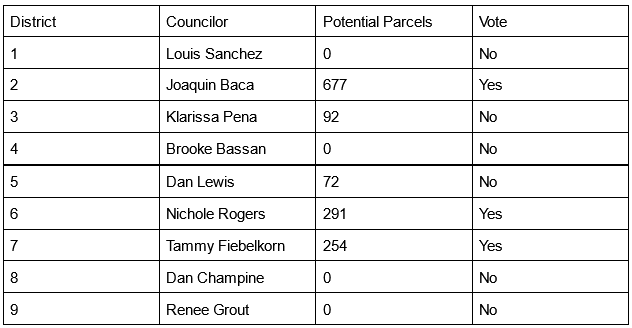

Another important difference: this amendment passed 7-2!

Why was a city which seemed unwilling to entertain any increases in density beyond casitas suddenly willing to adopt relatively expansive changes in housing development? What changed?

My own city council member, Renee Grout, was one of those who voted against the initial two amendments, but who voted in favor of the more comprehensive change. I had a chance to speak with her policy analyst, Rachel Miller, who explained to me some of her reasoning.

First, was the acknowledgement of at least the basics of the problem. She agreed that housing prices were rising too quickly, that increasing the housing stock was necessary to mitigate that problem, and that Albuquerque could not build enough housing through green-field development, that is, by developing currently undeveloped land. As usual, the disagreement was not over the facts of the matter, but the much more common disagreement over values. Where and how dense infill development gets built was more important to her than getting it built.

Second, the district she represents was not affected. The changes in building ordinances were limited in geographical scope such that no area within District 9 was included. One of her motivations as a politician is to keep angry NIMBYs out of her office. She accomplished that by ensuring that none of the ones who live in her district were affected.

I will point out that Miller claimed that Grout opposed the duplex amendment because the affected area would extend into her district and supported this one because it would not. This is incorrect, as the duplex amendment only extended to the area around Central Ave and Wyoming Blvd, while district 9 ends at Eubank Blvd. That Grout may have voted without understanding the duplex amendment is unnerving, but also goes to show how important perception is compared to the particular details of the change. And also that persistence can pay off!

Third, Councilor Grout was influenced by the votes of her party colleagues. All four of the Republican council members voted in favor of the amendment. Their support was likely led by Dan Lewis, the Republican co-sponsor of the amendment. Lewis was the former President of the city council, and is influential among his Republican colleagues, including with Grout. He has also been fairly consistent in his support for and financial ties with developers. In fact, he got himself into some trouble with the state ethics commission over those financial ties. But it is this interest that likely explains his rather jarring switch from voting against both the casita *and* the duplex amendments to co-sponsoring this far more radical zoning amendment! Developers aren’t going to make much money off of casita additions or duplex conversions. But reducing barriers to building new multi-family developments and making opposition to those developments more difficult? Dollar signs.

From this lens, council members changed their position on the IDO zoning amendment for two reasons: first because limiting the geographical scope of the changes controlled opposition. Districts 2, 6, and 7, the only ones affected, are filled with supporters. The other districts, filled with potential opponents, wouldn’t be affected, thus motivating supporters to show up without galvanizing as many NIMBYs into action. The thing about NIMBYs is, its *their* backyard they’re worried about. Thus you can break apart a NIMBY coalition by only giving some of them what they want. In this case, the geographical limits are even more strategic, because the districts left out were the most suburban. While I think everywhere could benefit from higher density, mixed use, and transportation mode diversity, focusing on urban centers and transit corridors definitely maximizes impact.

The second reason is that, making the changes in the amendment *more* radical actually galvanized developers and their supporters, thus creating a positive constituency. Compromise has many downsides, but we don’t tend to think of reduced support as one of them. Getting support for what we want is practically the purpose of compromise. So it can seem rather odd to consider that opposition to the casita amendment and the duplex amendment may have been made worse by their compromises. But success in democratic politics isn’t just driven by avoiding conflict. Quite the opposite. Accepting that there will always be disagreement about important policies should emphasise gaining support rather than just reducing opposition. In the case of housing, NIMBYs and YIMBYs are fundamentally opposed to the things they want. Offering the smallest possible change as a compromise is like telling someone “it will only hurt a little bit” at the doctor’s office. They don’t want it to hurt at all! By getting other groups, in this case developers, interested enough in your policies you can instead get the support you need without needing to try to convince NIMBYs.

It may sound odd for an incrementalist like myself to be advocating for more radical policies. Even policy scholars often mistake incrementalism as inherently favoring the status quo and focusing on taking small steps. But this is a drastic oversimplification. Albuquerque’s successful IDO amendment shows exactly why. Getting the size of the increment right is certainly important. This is exemplified by the benefits to limiting the zoning changes geographically. But that doesn’t mean every aspect of a policy change has to be conservative. In this case, by keeping the geography small, the policy change itself could be much more radical. Rather than merely allowing casitas or duplexes, the new IDO amendment allows a myriad of dense residential constructions. Where the previous two amendments would have only ever amounted to a few hundred of the tens of thousands of new units required, this new amendment actually lays the groundwork for substantial density improvements in the allowed areas. Careful selection of the appropriate increment, in conjunction with orienting policy changes to attracting positive constituencies can lead to a policy that is both clearly incremental in some ways, but radical in others.