Skyrocketing Profits? An Out of This World Economy?

How to Organize An Economy on the Red Planet

Our terrestrial economic system is already complex. But adding in the challenge of the harsh Martian environment makes it all the more impossible to know exactly how the economy will need to be organized. On the hand, terrestrial market systems that rely on decentralized coordination are able to achieve relatively stable outcomes in the fact of complexity as opposed to a command economy. On the other hand, the pursuit of profits and market efficiencies in terrestrial economies often does so in such a way as to sacrifice resilience. It leaves little slack in the markets for necessary goods and services, and often allows for critical infrastructure and environmental services to decay.

Not to mention that on an individual level people are routinely left out of even successful and prosperous economic periods. Problems like homelessness and malnutrition are rife in market economies. And while these problems are tragic enough as it is, in a place as hostile as Mars, something like homelessness is a death sentence. Even a place like Finland, which has nearly zero chronic homelessness and is considered a model for success on Earth, would be a failure on Mars because humans will not be able to survive outside of the habitats they make even temporarily.

For example, shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that most contemporary market systems emphasized the resource efficiency of supply chains rather than their resilience. Climate change in general illustrates how vital life support systems on Earth end up being neglected because they have no explicit “price.” How could the Martian economy fill the gaps from its terrestrial counterpart? And how could Martian society possibly run an economy with so few and small scale errors that they don’t threaten human survival? Is it even possible to reach that level of perfection?

Such an economy would have to prioritize resilience, work satisfaction and buy-in, decentralization, and self-sufficiency in order to succeed under such extreme conditions and with such high uncertainty. Moreover, just because these problems are so much more pronounced on Mars, doesn’t mean they are absent on Earth. Could we also adopt some of these economic forms here? What can we learn about making our terrestrial society better by thinking about how to run a Martian one?

Imports, Exports, and Industries

The first major economic problem is the balance of imports and exports. Imports will be unavoidable, but hugely expensive. To succeed in this balancing act, a Mars city state will need to be self-governing and agile. If the cost of importing the necessary goods from Earth is greater than the price received from exports, whatever organization makes up that deficit, be it some terrestrial state or company, will have an inordinate amount of control over the economy of Mars. Martian residents, in that case, would begin to feel less like colonists settling a planetary frontier and more like the indentured subjects of the outer space equivalent of the East India Company.

Martian citizens will have to consider two main factors. First, minimizing imports. Martian citizens will need to carefully consider the pros and cons associated with local production and Earth imports. While maximizing local production seems like an obvious good, there are complications. Human resources are limited. Are expensive Earth imports potentially worth it if it means being able to shift workers to more value added exports? Or does the high price of imports mean the economy will be better off sacrificing exports in favor of higher levels of self sufficiency?

Second, what products and/or services will be most valuable to provide to Earth? Which of these will be easiest to produce on Mars? Will there be advantages to manufacturing in Martian conditions that make the export of physical goods advantageous? Or perhaps a service or knowledge based economy that minimizes the expensive and error prone transportation of goods through space will work best? Abstract calculations made in advance of settlement are unlikely to prove true. Needed most is a flexible system for quickly learning via experience. Maximizing learning in such a complex endeavor will likely be too big a job for a small cadre of experts. Every citizen will have to be thoughtful about economic policy. Providing every citizen with an ownership stake in the colony will make thinking about how to improve the trade balance the job of every resident.

Importing From Earth

Much of the cost of importing goods to Mars from Earth will be transportation related. Perhaps someday some currently unknown and unforeseen technological revolution will make space travel cheap. But even the most optimistic predictions using realistic expectations of what we can do with current technology lands at around $500/kg from Earth to Mars. At the outset, a great deal will have to be imported from Earth. It is likely that resources such as food, water, and raw materials like building materials and metals could be produced in situ relatively early on. All other supplies, including the machinery required for producing these initial resources, will need to come from Earth, much of it will need to arrive before settlers. One estimate of this initial mass is 500MT. Thus the initial investment is $250M for transportation plus the procurement costs of the supplies. These costs will vary considerably, being relatively low for items like food, but very high for technically advanced supplies like construction and refining equipment. We will estimate a total initial cost of $1B.

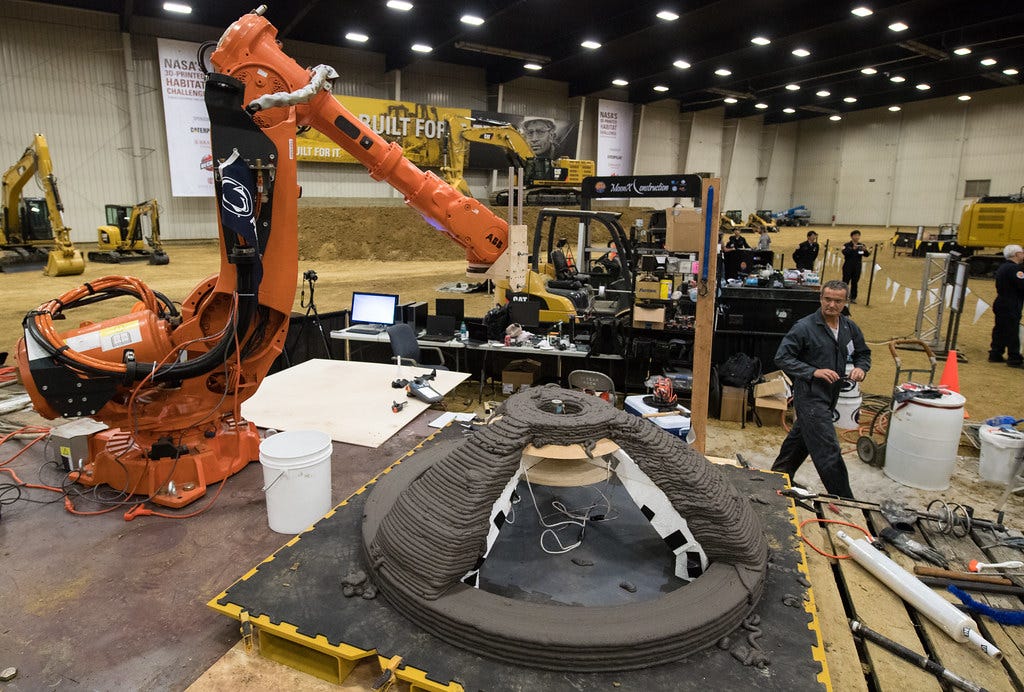

Ensuing shipments from Earth will include manufacturing equipment, like 3D printers, in order to help achieve some self-sufficiency. These will have to be designed with large enough tolerances in order to function in the harsh and low-gravity Martian environment. As energy is key for setting up the rest of the colony, early imports will include specialized parts to begin work on constructing a nuclear reactor and setting up the mining and refining of nuclear fuel.

Exporting From Mars

It is difficult to anticipate what Mars colonists could produce that will be valuable enough to ship back to Earth. We only have very rough data on the mineral composition of the Martian surface and subsurface, with some potential for extracting metals that are relatively rare on Earth. And some possibilities, such as whether certain manufactured goods or biotech products might be best or only feasible to make in Mars’ low-gravity conditions, are almost unknowable in advance. The question is equivalent to asking an early American colonist what goods the United States would best excel in making after the industrial revolution.

As we have proposed for the technical design of the colony, we recommend provisioning pods with equipment for prototyping and experimenting with various means of economic production, including 3D printers and other low-weight equipment. Most of all, colonists would need to be afforded the time to experiment and debate with one another. Discerning the most lucrative economic activities on Mars can only be the result of dedicated hands-on-learning within an environment that fosters scientific learning and small-scale technical innovation.

Democratized Economy

As discussed above, a far more important consideration than attempting to divine the right combination of imports and exports is how to devise an economic system so that it arrives at the optimal mixture. We believe that an economic system with high-levels of democracy is essential for this task, which has the additional benefit of providing great worker buy-in and equal or greater efficiency.

First, it is already well-known on Earth that stark economic inequalities often lead to dangerous levels of political instability. Since we want a Martian colony to be resilient by design, rather than reliant on the use of force, the economic system must self-correct to keep inequality low enough to maintain political stability. Any Martian citizen falling through the economic cracks not only has their own life put into jeopardy--given that there are no “free” life support systems on Mars--but could be a risk to others. As such, our Martian market is based on small cooperatively owned firms and provides all residents an ownership stake in the colony as a whole. These firms would not only exchange goods and services through a market but also send representatives to economic counsels and co-governed credit unions to coordinate collective infrastructure projects, decide prices for necessary goods and disposal of waste, and set workplace-related regulations and laws.

Cooperative ownership is similar to individual ownership, except ownership rights are vested in workers as a collective rather than individually. Rights are not connected to ownership of shares, but directly to membership in the cooperative. Members have equal say in decisions, and rather than shares which represent the value of the workers portion of the enterprise’s assets, each employee has an account to which surplus or loss is allocated periodically. The members of the enterprise can set the initial membership fee to whatever they wish, and that fee sets the initial balance of the account. The accounts are non-transferable, thus protecting from hostile takeover, but can be drawn on to certain limits set by the enterprise members to protect liquidity. Cooperative ownership protects against many of the trade-offs of individual ownership and can expect a much greater degree of equality than any traditional corporation.

A further justification is that a Martian colony cannot buffer a volatile labor market. Everyone capable of working must work. Even the relatively low “natural” unemployment rate that pervades economies based on non-cooperative firms will be too high for Mars. What is a person to do if they cannot work towards the success of the Martian city? The harsh conditions necessitate an economic system where all able bodied adults are economically productive and not supported entirely by all the others. Of course there will always be conditions under which some residents must support the others: the elderly will retire, people will get sick, residents will have disabilities, and people will get pregnant. But the overall economic principle should be that everyone must be afforded the ability to labor under good conditions. Cooperative organization ensures a mutual commitment between firms and employees.

Second, a decentralized economy of small-scale firms, while sacrificing economies of scale, will help ensure the resilience of the entire colony. If the colony’s oxygen production were located in one area, which suffered an accident or disaster, the entire population would be put at risk. And the physical design of the colony will make sure that needed infrastructure cannot be hoarded by any one group of citizens but is equally available.

Third, by keeping firms small and providing all workers with an ownership stake, we avoid the risk of residents becoming alienated or demoralized. They cannot see themselves as “wage slaves,” because they are also proprietors. While there is tolerance on Earth for employees who absent-mindedly run through their work tasks and shirk as much as possible or labor away at “bullshit jobs,” there is no room for such waste of human potential on Mars. The economic system needs to maximize the degree to which workers find their labor to be meaningful. And affording all workers the ability to contribute consequentially to how their workplaces are run and to be incentivized to innovate new products and techniques does just that.

Data from plywood cooperatives in the pacific northwest indicates that employees are more likely to sacrifice earnings or wages to save a firm than investors or private owners. The Mondragon group in Spain grew four times faster than comparable corporations during Spain’s boom economy. And during the recession, they actually increased investment, growing the company while other corporations cut labor. Cooperatives in former Yugoslavia also tended to favor investment over increasing wages. The evidence clearly demonstrates that worker owned and operated firms are optimal for situations where total “buy-in” is required for success. And it is clear that workers self-educate to a greater extent, rise to meet the challenges presented by self-management, and achieve equivalent efficiencies.

Furthermore, a decentralized network of small producers will ensure a rapid pace of generating new innovations and ideas. One of the major challenges for the Martian settlement is to recreate the intelligence and ingenuity of several billion Earthlings with only around one million colonists. Such a colony will simply be too small and precarious to tolerate monopoly or oligopolies. The barriers of entry cannot be too large, so overly scaled and centralized infrastructure is to be avoided. Just as networks of small-scale Danish wind turbine-builders out innovated NASA, so too would a web of artisan manufacturers on Mars working together be expected to figure out what will invariably elude even the smartest Earth-based analyst.

Finally, we want to continually reinforce the skills necessary for residents to productively work through conflicts. As discussed above, organizations that work constantly on the edge of disaster cannot afford members who are unable to work cooperatively. They must embrace the inevitability of conflict and be capable of working through disagreements productively and without irreparably harming social relationships. Acting as a citizen of an enterprise as well as a citizen of a state will improve each citizen’s capacity for doing the activities of governing. Organizing the economy through small-scale cooperative firms will ensure that citizens’ apprenticeship in democracy will continue on from their schooling years into their adult lives.

We’ve already discussed how Mars is basically a hellscape. And we’ve made the argument that the low margins for error and high uncertainty inherent in the endeavor of living in such an environment requires more democratic mechanisms of governance than we have here on Earth. The same principle applies to the economy. We may be tempted to cede authority to a small group of subject matter experts. But even these experts are only human. They will make mistakes and they will have biases. Limiting decision making power even on the basis of meritocracy simply means that there won’t be anyone available to call out those mistakes and biases. Mars does not offer the leeway for those kinds of errors, and prediction of complex systems is simply out of reach of any human, no matter how smart.

But society is so much more than technological development, politics, and economics. Community, the places in which and the people with which, Martians will live is just as relevant to our success and survival on the red planet. We will discuss how a Martian settlement can enable thicker, more supportive communities in our next installment.

One wonders if a resource management workshop focused on resolving a rotation of one given Mars-wide problem a week could also work, à la Buckminster Fuller’s World Game: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Game

Perhaps this exercise would be best left to the planet-wide economic councils, who could be best entrusted with the Game’s principle of Spaceship Earth (or Mars, in this case)