Why is it that whenever a new apartment or condo building goes up it all looks the same? Big square five-over-one's abound. Modern dense housing can sometimes look like nothing more than a bunch of blocks. Every new building in every American city seems to look just like every other new building.

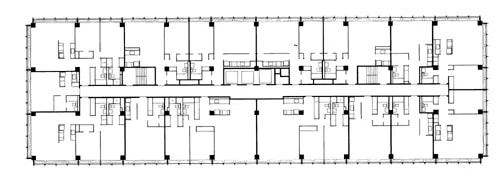

There are many contributing factors, but one major one is emergency egress regulations. The International Building Code (IBC), which is actually mostly just American, requires buildings over three stories tall to have at least two sets of egress stairs in case of a fire or other emergency. Those stairs must generally be inside the building, and must be at least 44 inches wide. This two-stair requirement limits building design, essentially requiring what is known as a double loaded corridor: a single corridor that splits the building in two connecting the two egress stairs with housing units on both sides of the corridor.

Most buildings with this floor plan have to be some form of rectangle. But it's worth it, because it ensures safety. With two stairs, firefighters can use one set of stairs to attack the fire and residents can use the other to evacuate. If the fire happens to spread to one stairway, there is a backup so residents can still escape.

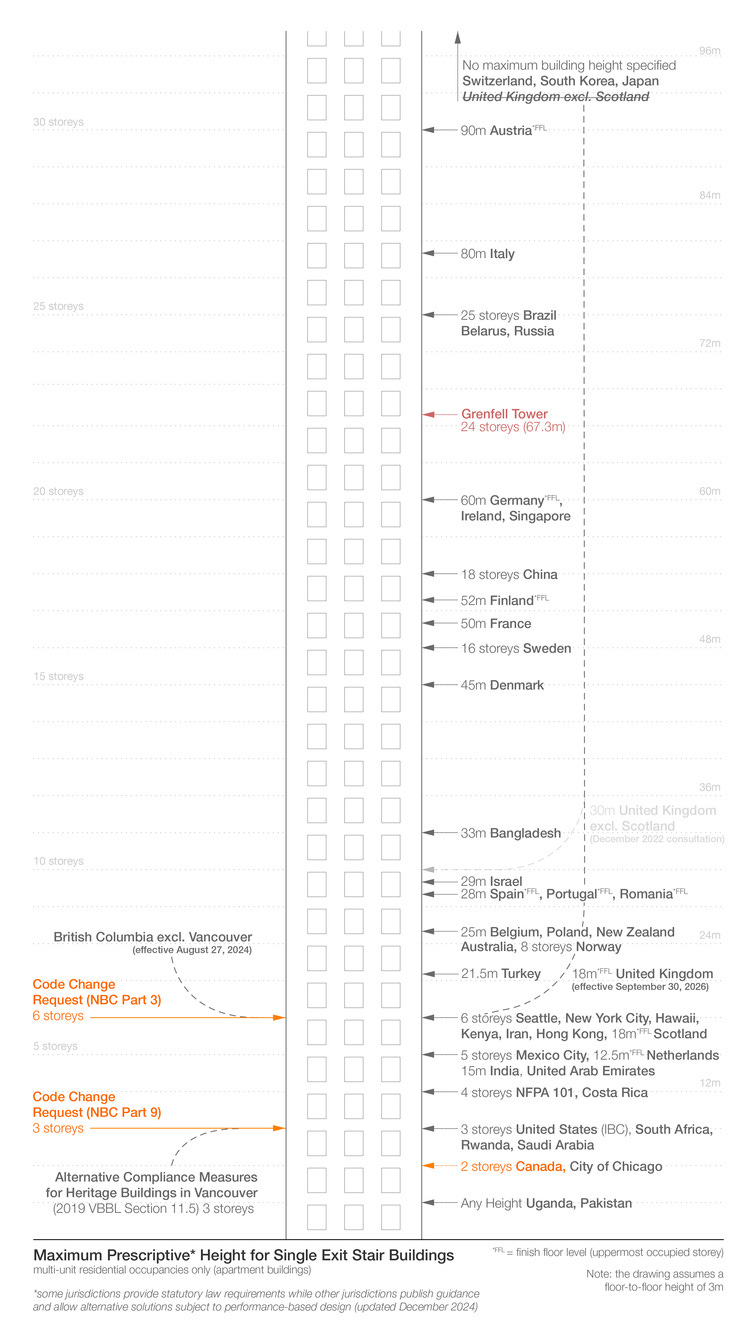

But most other countries don’t require this. In Europe and Asia, buildings up to six stories are often allowed to have only one set of stairs. In countries like Switzerland and Japan single stair buildings can be any height; there is no limit! If redundant stairways are so important for safety, then why do most other countries not require them?

It seems obvious that the more egress routes there are out of a building, the safer it is. But safety is rarely so simple. It may be that by defacto outlawing single stair buildings, the United States actually makes people *less* safe.

Safer Housing

First, being overly cautious can lead to trade offs that actually *reduce* the overall level of safety. Political scientist Aaron Wildavsky describes this issue as “trials without errors”. Take, for example, new medical treatments. On the one hand, a completely unregulated market risks endangering people with ineffective snake oil, or worse, actively harmful so-called treatments. On the other hand, a clinical trial process that is too onerous risks harming those waiting on the new treatment. In a similar vein, policymakers concerned about the safety of single stair buildings risk ignoring the very real safety risks we experience in their absence.

Detached Housing

Because they don’t require a double loaded corridor, single stair buildings can fit on small or oddly shaped lots. Currently, those sorts of lots can only accommodate detached housing. This means, in turn, that developers aren’t going to build single stair buildings instead of double stair buildings. They are going to build single stair buildings instead of detached housing. So how safe are single stair buildings compared to detached housing?

Detached housing follows the International Residential Code (IRC) rather than the IBC. They lack requirements for fire and smoke mitigations systems, the use of fire and smoke resistant or non-combustible materials, or even for designs that slow the spread of fire and smoke. As a result, detached houses are some of the most dangerous buildings we encounter when it comes to fire safety.

The 2020 report on Fatal fires in Residential Buildings paints a grim picture of detached housing. One and two family dwellings, those dwellings regulated by the IRC rather than the IBC, made up 79.4% of fatal fires in residential buildings. Nearly all of these start inside homes due to acts of carelessness, such as falling asleep with a lit fire such as a cigarette. Because detached housing has so few fire mitigation regulations, nearly 80% of these fires spread beyond their room of origin. On the other hand, automatic extinguishing systems, i.e. fire sprinklers which are not required in detached houses, were only present in under 2% of fatal fires, a total of 61 incidents between 2018 and 2020.

If developers are not allowed to build single stair buildings, they don’t build more double stair buildings. Instead they build more detached housing. Legalizing single stair buildings would therefore replace some of the most dangerous housing stock we currently have. This is one way that single stair buildings actually improve safety.

Double-Loaded Corridors

Yet, even if we compare the safety of single stair buildings to their double stair counterparts, the safety benefits of that extra set of stairs aren’t so clear cut. Single stair buildings may still be safer.

Architects can make buildings fire safe in a myriad of ways, and they are not all equivalent. From the field of chemical engineering, Trevor Kletz introduces us to the idea of “inherent safety”. Summed up with the phrase, “what you don’t have can’t leak”, safety interventions that make harms physically impossible are preferable to engineering interventions that attempt to mitigate harms only once the worst has already happened. In our case, fire can’t catch what it can’t burn.

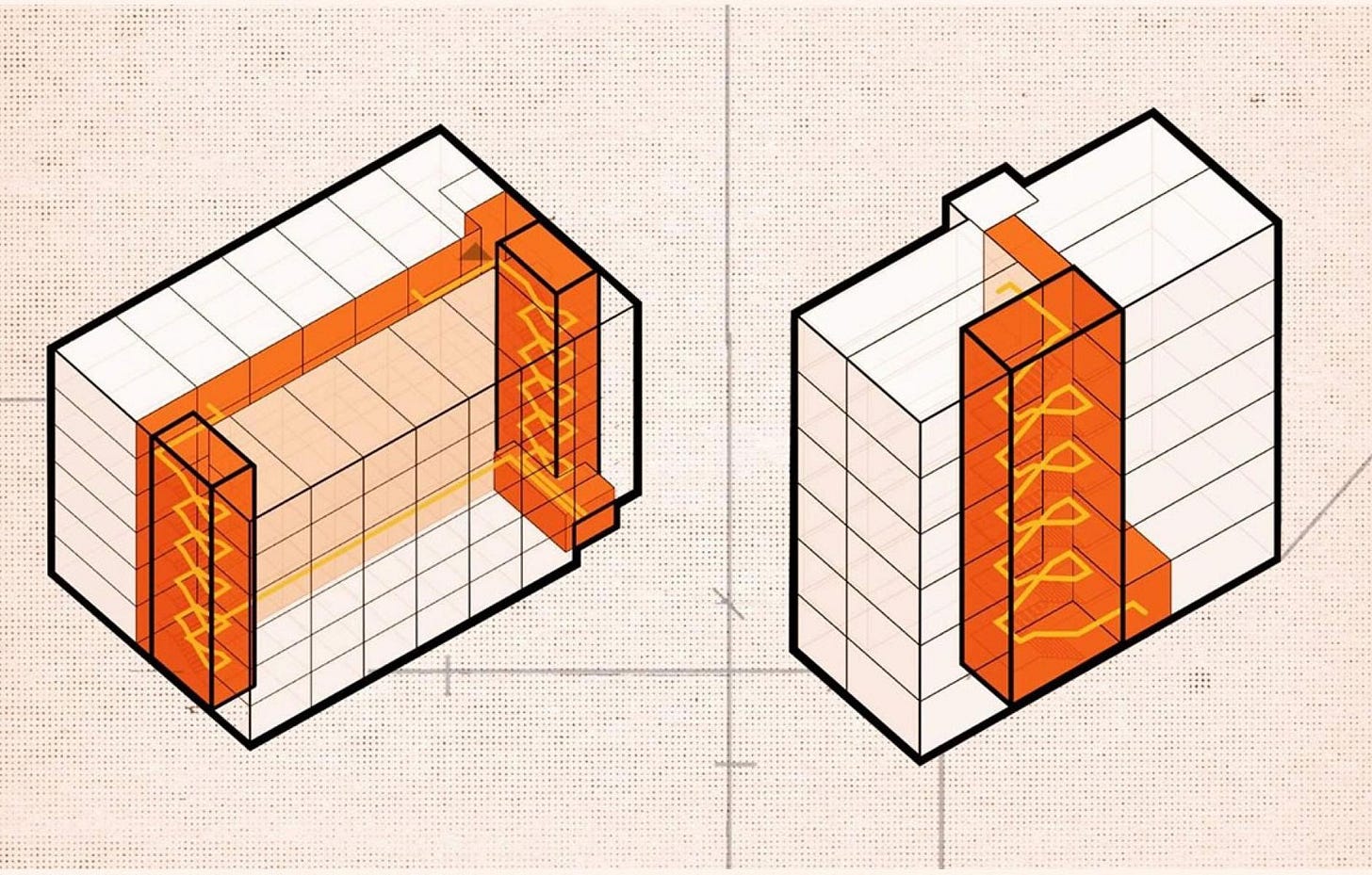

According to this principle, the addition of a redundant staircase is a fairly poor safety feature. First, the staircase only improves safety once there is already a fire. It doesn’t prevent fires from happening or keep them from spreading. One of the reasons other countries do not require a second staircase is because their mid-density residential buildings tend to use masonry framing, while American buildings tend to use wood framing. A single stair building made of non-combustible materials is better than a building with two sets of stairs made of combustible materials.

Double stair buildings are no exception. Having two or more sets of stairs often necessitates a double-loaded corridor design, which actually creates the perfect environment for fire and smoke to spread. In order to get to the egress stairs, residents have to go through a long, open, continuous corridor which is an easy avenue for fire and smoke. The stairs only help if you can safely get to them, and the fire danger of double loaded corridors can make evacuating more dangerous. This is part of why, so often, fire officials instruct the residents of these buildings to stay put in case of a fire and not to evacuate using those extra stairs at all!

Another reason to prefer inherent safety is that active safety systems can add complexity. The way they interact with other systems can create unsafe situations, and when they fail, those systems that were meant to improve safety can actually turn deadly.

The egress stairs themselves can also fail and turn an otherwise minor incident deadly. One of the reasons that fire crews so often advocate for two stair building codes is it enables them to segregate the stairs; they use one set of stairs to attack the fire while residents use the other set of stairs to evacuate. But that is much more difficult to coordinate in practice than it sounds in theory. Once firefighters open the door between the stairs and the source of the fire, smoke fills the stairwell and can contaminate all the floors above. Any residents unaware of which stairs to take can be put in even more danger than if they had stayed in place. In 2014, a Manhattan man evacuating a high rise apartment with two sets of stairs had already begun to descend when firefighters used the same stairs to attack the fire. When they opened the door to the stairs, smoke filled the corridor and the evacuating man above died of smoke inhalation.

So a second set of stairs, it seems, is not necessarily safer unless you add even more active safety systems tacked on! You can’t just add a set of stairs, those stairs need to be pressurized so smoke can’t get in. And, just in case smoke gets in, they also need an emergency venting system so the smoke can escape. And hallways need a fire suppression system to keep them safe so residents can evacuate. And the whole building needs a PA system so that fire crews can coordinate which stairs they use and which ones residents use as an egress. And what if any of these systems fail, or worse, cause the fire? Yes, a PA system might be necessary, but the more electric systems are in a building the more likely someone is to make a mistake and cause an electrical fire. How many backups to the backups do we need to be safer than a single set of metal or concrete stairs outside the building?

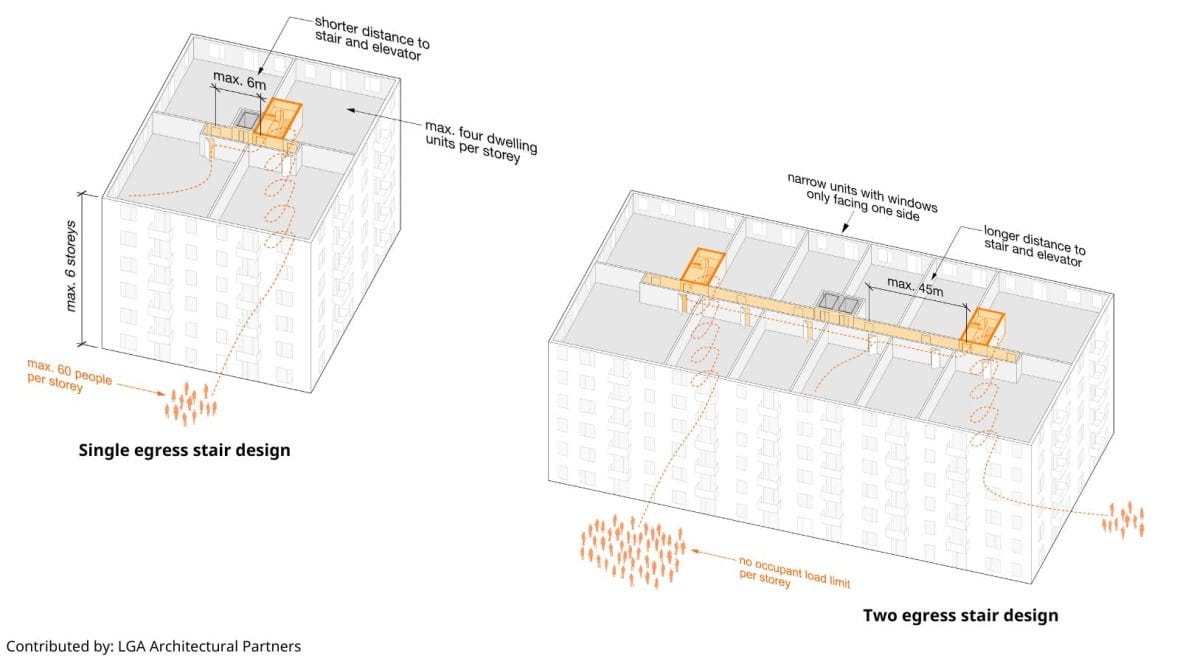

Design limitations of including two sets of stairs also tend to result in very long buildings. The egress path, that is the distance from the furthest point in a unit to the stairs, can be as far as 250 ft. But if one of the two stairs is rendered unusable, either because it was contaminated with smoke or firefighters are using it to attack the fire, that distance can double. Because single stair buildings can be much smaller, egress distances are much shorter, further increasing safety.

Safety In Practice

But do these benefits play out in practice? Places like Switzerland and Japan, where there are no height restrictions on single stair buildings, do not have worse safety outcomes than the United States and Canada, which do. The United States has a relatively high fire fatality rate of 11 deaths per million people. Switzerland has no height restrictions on single stair construction, and they have a fire fatality rate of 2 deaths per million people. Japan also has no height restrictions for single stair buildings, and has the same fire fatality rate as the US. Singapore’s height restriction is 20 stories, and they only had 1 fire fatality in 2020 (not high enough to have a statistically significant rate). Nordic countries all have a fire fatality rate of 9 deaths per million people despite having restrictions that range between 15-18 stories. Overall safety outcomes don’t seem to depend much on height restrictions for single stair buildings.

Unfortunately, these comparisons don’t mean much statistically. There could be a lot of other factors confounding these numbers. Countries that rely on passive safety regulations, such as non-flammable building materials, have fire safety results that vary just as much as among countries with differing height regulations. And Japan is the only country whose outcomes are getting worse despite relatively consistent regulations. In their case, an agining population and unusually high rate of suicide by fire are the likely causes. Fortunately, fire fatalities are generally low enough that it is difficult to suss out the causes of different results between countries. Unfortunately, these comparisons can’t really prove the safety of single stair buildings.

In order to prove that these theories about inherent safety and trials without errors hold true in real life, we would have to control for a lot more variables. We would need to be able to compare single stair buildings to double stair buildings in the same place, so that things like demographics and building material regulations aren’t different. In other words, we need a natural experiment.

Fortunately, we have just that. Honolulu, Seattle, and New York City have all legalized single stair buildings up to 4-6 stories tall. Otherwise, they all use the IBC as the basis for their building regulations. In New York, there were two fatal fires which killed three people in modern 4-6 story single stair buildings over the last 11 years. This yields a similar fire fatality rate in other 4-6 story buildings. Neither fire spread beyond the unit in which they originated, meaning that the number of egress stairs was not a factor. In Seattle, there was only one fire fatality in similar buildings during the same period. Egress stairs were also not a factor in this case.

It is notable that the total number of fire fatalities in these buildings is very small. On the one hand, three fires and four fatalities between two major cities over a decade is not enough to generate statistically significant results. On the other hand, the extremely low number of fire fatalities in these buildings is itself good evidence for their safety.

One important thing to note: safety is, in many ways, attained through our dedication to prioritizing it. It is not always possible to achieve the level of safety we want with only inherent or passive safety systems. A key variable that advocates both for and against single stair buildings often overlook is the inspection and maintenance of safety systems.

Laws legalizing taller single stair buildings, like in Seattle, often do a good job of requiring those buildings to be more inherently safe. They include maximum egress distances, maximum floor occupancy, and require varying degrees of fire resistant or non-combustible materials. But as we’ve seen, fire suppression systems are key to safety as well. As lawmakers in more and more states consider legalizing single stair buildings, they should also consider improving inspection and maintenance requirements for fire alarms and suppression systems.

It makes intuitive sense that the more sets of stairs a building has to evacuate the safer it is, and that the taller the building the more important that becomes. But every safety measure has trade-offs. Inevitably, some of those trade-offs end up reducing safety overall. Double stair regulations are just such safety measures. If all other things are equal, having two sets of stairs is safer than one. But all other things aren’t equal.

Requiring double stair designs in buildings as low as four stories forces small lots to be primarily single family homes, which are dramatically less safe than tall single stair buildings. And single stair buildings can more easily take advantage of inherent and passive safety designs, which are far superior than error prone active safety interventions like double stairs. Single stair building designs improve safety while simultaneously providing other benefits that may help alleviate the housing crisis in many American cities.

More, Inexpensive Housing

One major cause of the housing crisis is a lack of supply. In many places, more people want homes than there are homes to go around. To make housing more affordable, developers will have to build more homes and increase the supply. But that is easier said than done. Upzoning, re-building denser housing on existing lots, can be especially challenging. Requirements for two stairs for buildings higher than three stories makes that denser housing take up a lot more room. As a result, developers often have to buy up multiple parcels of land before they can build. Each unit is more expensive to build and therefore more expensive to buy or rent. No wonder every new development is for luxury apartments!

But single stair designs can fit in lots previously sized for detached housing. And the flexibility in design they can afford also allows developers to build on lots with unusual shapes and dimensions. For example, in Denver’s East Colfax area, zoning for most parcels allows buildings to be five stories. The main problem is that parcels are too small to redevelop with higher buildings largely due to minimum parking requirements and the two-stair requirement. Worse, many buildings go underutilized because the high density zoning over values these properties, discouraging investment. Fortunately, Colorado recently passed HB25-1273 which legalizes single stair buildings up to five stories in cities with a population over 100,000.

Better Housing

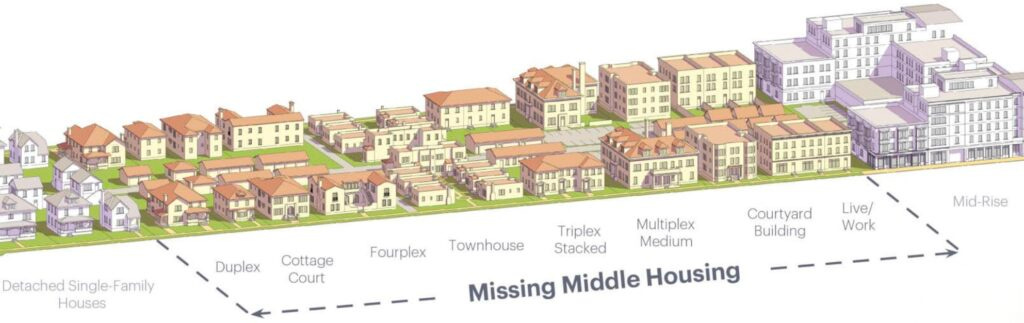

Because single stair buildings can be smaller than those with two sets of stairs, they better enable gentle density. In many cities, like Toronto, much of the new dense housing takes the form of huge high rises. These high rises often line major thoroughfares and transit routes, only to give way immediately to single family neighborhoods. I personally wouldn't mind living in a high rise. But I also wouldn’t want one right next to my single family home. It certainly makes for a sharp juxtaposition.

What I wouldn’t mind are a few low rise, four to six stories, apartments mixed in to my neighborhood. Single stair construction can enable these sorts of buildings which can help maintain the character of neighborhoods while still enabling upzoning. Furthermore, these smaller single stair buildings could provide a buffer between high rise residences and single family homes. Cities will inevitably need to convert some detached housing, especially in those neighborhoods that are close-in to the city core, to denser forms. But we have a choice of how to do that: with double (or more) stair high rises surrounding islands of detached housing, or with the gentle density of single stair buildings.

What's more, designers can make single stair buildings in a myriad of styles that fit with the character of nearly any neighborhood. Even relatively inexpensive projects don’t have to be the big square bricks that double stair buildings tend to be. Vancouver and Denver have both held design competitions to show just how interesting, beautiful, and affordable single stair developments can be, to encourage creative thinking, and attract development now that single stair buildings are legal in both cities.

The diversity of designs also means that single stair buildings can support a greater diversity of units. It is difficult for double loaded corridor buildings to accommodate more than one bedroom because, other than corner units, they only have windows on one wall. It is much easier to build two and three bedroom units in single stair buildings. One bedroom units are fantastic for housing young professionals or new couples! But we need to build new housing for families too, and single stair buildings can help us do it.

Single stair buildings are far from a panacea to the housing crisis. Zoning reform, transit oriented development, NIMBYism, and more are all battles we will have to fight. But single stair designs offer flexibility and incremental development that will make building the housing we need both easier and less painful, even for the NIMBYs. And we might even be able to make the places we live safer in the process.