I have to be up by 5:30 in the morning, but at 11pm I’m still awake. In six and a half hours I will have to cook breakfast and make my wife her lunch before she leaves for work, but right now I’m staring at a zoom meeting on my laptop. The Albuquerque city council is debating a zoning amendment to allow duplexes in some single family R1 zoning, and I signed up to give public comment in favor of the amendment.

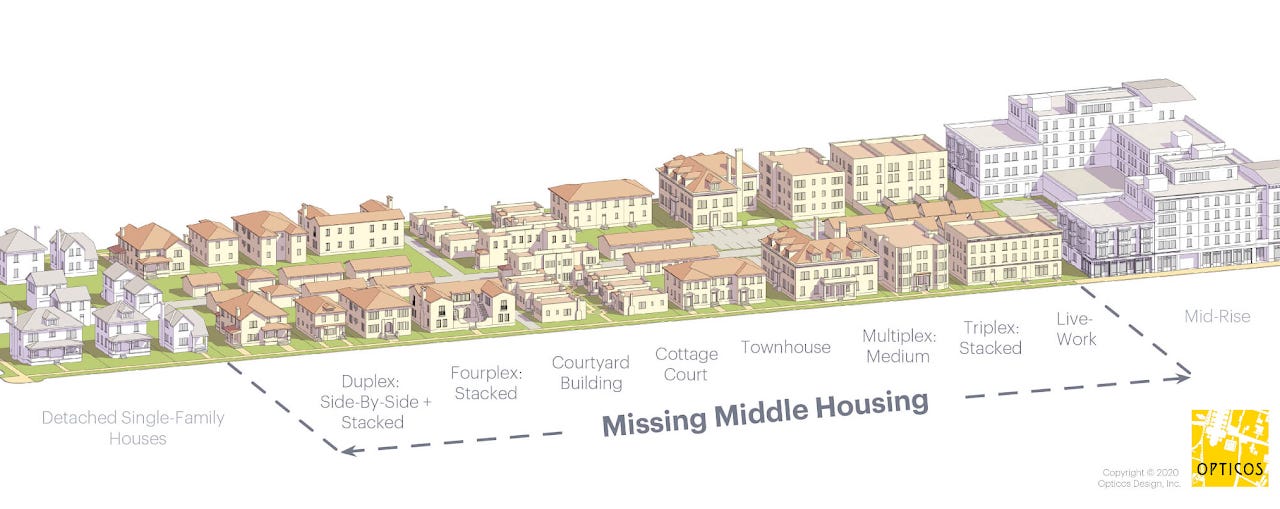

Albuquerque, like many other cities, has a housing shortage. The city is estimated to need nearly an additional 30k units in order to prevent out of control rent and housing price inflation. All this while about 60% of the city’s area is zoned exclusively for single family homes, or R1. Albuquerque’s problem is, really, the same problem that nearly every mid sized American city is experiencing: sky rocketing rents and home prices in response to a housing shortage that is difficult to deal with because zoning prevents the kinds of density increases that allow for homes where people want to live.

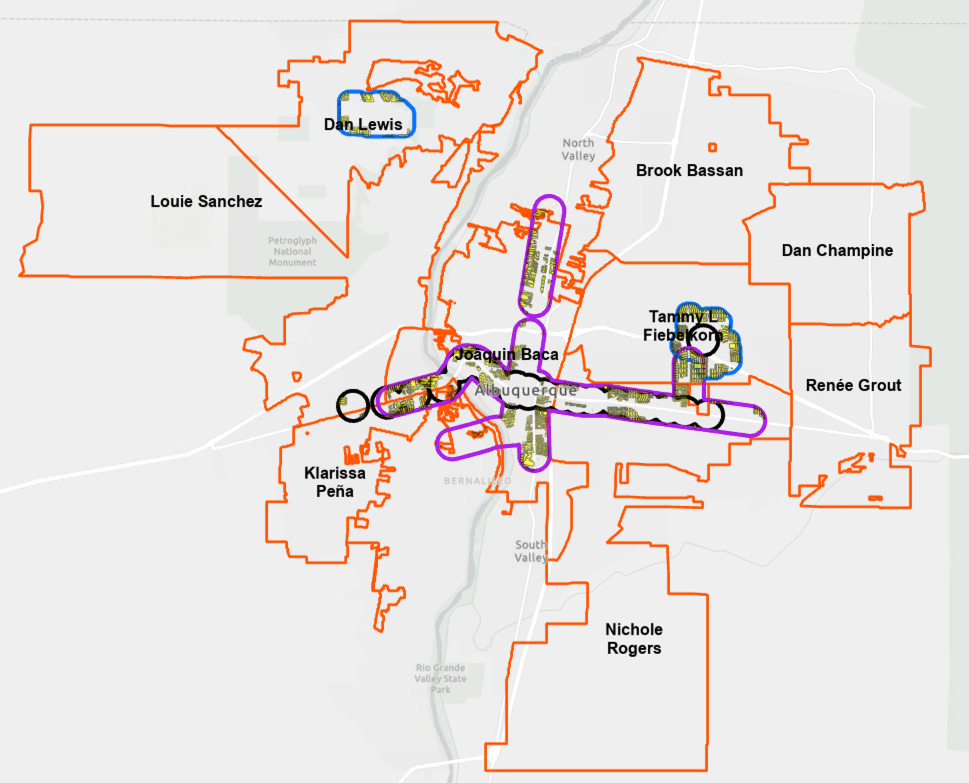

The amendment I was waiting to comment on was designed to be an incremental step towards alleviating just that problem. It would have allowed for duplex conversions by right in areas within ¼ mile of a transit corridor or an urban center. The amendment also only covered conversions, so tearing down an existing home to build a new duplex would have required the normal zoning exemptions.

The amendment did not pass. I sat for hours into the late night waiting for my chance to speak for a single minute in order to have my voice heard. But it didn’t change the outcome. After my initial feelings of frustration subsided from the sense that my voice doesn’t matter at all I was left asking myself: why did it fail?

The amendment was incremental, and designed to be responsive to the concerns of residents. In 2023, Albuquerque’s city council changed the zoning laws in the city to allow casitas (also known as accessory dwelling units or mother-in-law suits) by right in all R1 zones. The proposal originally included duplexes, but the sponsors couldn’t get sufficient agreement within the council to pass the change with duplexes included. So duplexes were removed in order to legalize casitas.

The duplex amendment was drafted in direct response to opponents of duplexes in this initial zoning change. Residents expressed concerns about developers buying up whole blocks of the city to convert single family homes into duplexes, destroying whole swaths of Albuquerque’s historic adobe homes. So the amendment only allowed duplex *conversions* by right. This change from the original proposal favors existing owners over developer. Existing owners are more likely to be able to afford a conversion, while developers have more incentive to build duplexes from the ground up using standardized floor plans and designs.

Concerns about parking and congestion were also common in discussions of the initial zoning change. So the amendment would not have covered the entire city. Instead it would have only taken effect within ¼ mile of transit corridors and urban centers. Thus, the only areas where single family homes could be converted are either: already served by ART and thus have an alternative to driving so new residents might not have to own cars, or in an area that already has nearby density and thus is already designed to either facilitate a car-lite lifestyle or to accommodate the parking needs that may accompany high density.

None of this seems to help explain the amendment’s failure. From the perspective of an urban planner, the duplex amendment was the ideal example of incremental development. It minimized the potential impact on locals while also focusing on the areas that would most benefit from increased density.

Councilwoman Fiebelkorn, who co-sponsored the bill, summed it up, describing how whatever change the council makes to appease opposition, they just come up with some new reason to reject it.

“It’s beginning to seem to me like what we’re really upset about is that we don’t want people living next to use who make less money. That’s really the only thing I can think of at this point, because we’ve addressed every concern over and over and over again.” - Tammy Fiebelkorn

It’s almost like they oppose it out of principle, rather than for some specific reason.

Indeed, NIMBY opposition to even the gentlest density increases, or the most cost effective transit projects, does not usually consist of technocratic objections. Instead they are driven by symbolic and moral factors. They simply see the proposals as ideologically opposed to their vision of the good life. It is a matter of incompatible values that cannot be solved by technical policy revisions.

But that doesn’t mean that NIMBY’s simply have to be defeated or avoided through state or national level policy. If technical changes to the duplex amendment were insufficient to sway them, what other options were there?

First, they might simply be avoided. It isn’t necessary to start densifying in R1 zones. Albuquerque, and other cities, are full consumer facing commercial strip malls that are mostly filled with dying stores and parking craters. Lifting height restrictions and making consumer facing commercial zones mixed-use by right (similar to Japan’s zoning rules where residential is allowed in nearly every zone) could add density in an area where there are no current residents to oppose it. While certainly some business owners would lament any change no matter what as well, many others are likely to see how having potential customers living literally above their shop could be beneficial.

Second, density could be framed more positively by policy itself. Sometimes compromise on a policy measure looks like an olive branch, a token of good faith. Other times it looks like an admission of guilt, that opponents were right about the risks all along and the compromise just acknowledges them. But what if, instead, the city asked neighborhoods to compete for the privilege of having restrictive zoning measures waved? I don’t know exactly what that would look like, but something of that general form would reframe densification not as change whose costs are made worth it by the benefits, but as a boon to be sought after. Such a system would also automatically filter out NIMBY opponents, who simply wouldn’t participate. Although it does risk the potential that no neighborhoods bother.

Another option might be to give them what they want. If they want more housing, just not in their backyard, then let them say no in their backyard. A zoning change could come with a mechanism for a neighborhood or community to vote to exempt themselves or opt out of the change. Certainly, some neighborhood associations might succeed, but others might find that their opposition isn’t actually representative of their communities. It puts the onus on NIMBYs to convince residents to support them, rather than the onus always being on the YIMBYs.

And as more parts of the city densify, some NIMBY residents will simply get used to density. They’ll see exactly what changes are in store, and that can make those changes much less scary. Plus, we might find that more robust inclusion of NIMBY residents reveals more nuanced positions in some than we see at city council meetings.

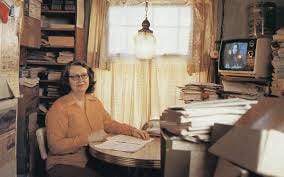

When Comanche Peak nuclear plant was slated for construction in Juanita Ellis’s back yard of Somervell County, Texas, she formed the Citizens Association for Sound Energy (CASE) to intervene. But she wasn’t opposed to nuclear power, she just wanted to make sure that Westinghouse and Texas Utility Electric were being as safe as possible. But nuclear licensing boards don’t give intervenors the opportunity to enter into a negotiations and dialogue with nuclear plants. You either oppose it or you support it. So Ellis and CASE opposed the plant. That is until after nearly a decade of obstruction the plant operator came to Ellis with the offer to have a permanent seat on the safety board for CASE and complete oversight privileges. Ellis accepted.

City council meetings work in much the same way. The council already has the policy written up. They are the only ones who can propose amendments, and the only ones that can have an actual discussion rather than a mere 60 second slot to say your piece. And in that 60 seconds, you either profess your support for the policy, or your opposition. Is it no wonder, then, that everyone who spoke against the duplex amendment sounded like a NIMBY?

Not every NIMBY is a Juanity Ellis. After all, Ellis herself became a pariah among many anti-nuclear advocates, who considered her something of a turncoat. There are, indeed, likely to be a substantial number of opponents to the duplex amendment that will oppose it no matter the nuance of the engagement they are afforded.

But Albuquerque’s experience with trying to allow for duplexes by right teaches us a lot about suburban NIMBYs wherever they show up! NIMBYs, no matter where we find them, are not interested in debating the technical minutia of policy proposals. Their opposition stems from ideological differences. Urbanists like myself often focus on the good in policies like the duplex amendment. We see it as a step towards a more utopian city! But NIMBYs see the risks. They have a more apocalyptic imagination of what such change might do. We shouldn’t dismiss that fear. Fear of change is a legitimate feeling, and in a democracy should not be sufficient grounds to exclude people from participation. But imagined fears are not unassailable. Just like in a horror movie, the rule is to keep the monster obscure in the dark because what your audience can imagine will always be scarier than what you can show them. The thing in the darkness is always worse than the thing in the light. So maybe what we need is a way to shine some light on the changes we think will make for better urban places?