The Fog of War

Why chasing certitude in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict only makes things worse

If you’re like me, you’re overwhelmed by the complexity of the situation unfolding in the Middle East. But you’re also bombarded on social media and in conversations by demands to choose a side (namely the side that the other person thinks is the morally “right” one).

Yet I struggle to find the firm moral and factual footing that many people on X.com seem to have. So much strikes me as uncertain and complex. But we’re awash in a stream of images, videos, and claims about Gaza, Israel, and Hamas, offered to us by people that desperately want us to believe a particular story about the Middle East.

But for such an urgent and high-stakes conflict, it’s hard to know who to trust. Forty babies were reported to have been beheaded by Hamas. But then it seemed like that was just a rumor or “fake news.” But then the Israeli government releases photos of babies allegedly killed, but not beheaded, during the conflict. A hospital was supposedly struck by an IDF missile. But by the next morning, it looks like it was really the hospital’s parking lot that was struck, and, according to the IDF, by a misdirected Hamas rocket.

Even what to call the event is unclear. It’s not really a war. But depending on which side you ally yourself with, it’s indisputably a “strike against terrorism,” a heroic rebellion against “occupiers,” or “a siege” committed by an “apartheid state.”

The most committed partisans would like you to know that this immensely complex conflict is really in fact very simple, if only you really knew the data and the on-the-ground history. To some supporters of Palestine, Israel is an illegitimate settler colonial state, a fact that makes their civilians fair game for Hamas fighters. Don’t you know how Israel turned Gaza into an open air prison? How many civilians have died at the hands of the IDF using American supplied weaponry? Isn’t clear how the blockade by Israel (though also by Egypt) keeps Gazans in abject poverty?

To listen to Israel-boosters like Ben Shapiro, Gaza is rife with terrorists who deserve nothing. Have you forgotten the 1967 war and Intifada-era bombings? Did it slip your mind that Hamas’ stated political goal is to drive the Jews into the sea? How can you fail to condemn the barbarism being spurred on by agents of Iran, or Hamas’ use of Gazan civilians as “human shields”?

This endless sparring over Israel reminds me of a paper by Daniel Sarewitz, where he argued that science only made environmental controversies worse. In noticing how expert scientific opinion seemed to do little to settle conflicts over climate change or nuclear waste storage, Sarewitz alerts us to the reality that the facts can’t replace politics.

Each side believes that winning that war of facts will assure their victory. They seem as convinced of that as they are of their own moral righteousness.

Sarewitz reminds us of the contested 2000 presidential election between Al Gore and George W. Bush. The results looked to be too close to call in Florida. But the Supreme Court intervened. Rather than wait weeks or months for a full recount, they decided in Bush’s favor and Gore immediately conceded.

But wait, wouldn’t it have been better to just count the votes? Shouldn’t something as important as the presidency be an evidence-based decision?

It ends up that the simple task of vote counting was in reality very complicated. Some of the mechanical voting machines made mistakes when voters tried to punch in their preferences. Some people got confused by ballot designs and apparently chose the wrong candidate or more than one. Expertise would have been necessary to really do the recount right. Mechanical engineers might have reduced uncertainty for the “hanging chad” problem. Psychologists could have plausibly deduced “voter intent” from ambiguous ballots.

But, given the stakes of the situation, and the fact that all expert assessments are incomplete and fallible, each side would have just promoted their preferred science, and championed only the facts that looked to pave the way to victory.

Sarewitz called this situation “the excess of objectivity.” For highly consequential decisions, we don’t suffer from a lack of scientific opinion but rather drown in it. Different scientific disciplines, divergent research methodologies, and incommensurable theoretical assumptions give us competing answers. And more science just as often raises new questions about what was previously settled fact. The Bush-Gore election showed that previously uncontested election results might have actually been decided by voting error.

Given that amassing ever more facts and expert assessment can’t even settle an election, doing the same for the Israel-Palestine conflict is unlikely to lead to consensus. But that reality won’t stop the informational battle being fought online and in the media. Each side believes that winning that war of facts will assure their victory. They seem as convinced of that as they are of their own moral righteousness.

Truth fanaticism adds an additional layer of tragedy to an already horrific state of affairs. It obscures the more fruitful pathways to reducing conflict. If Sarewitz’s assessment of environmental controversies applies here, and I think it does at least a little bit, then we’ll get nowhere trying to definitively determine who is most morally culpable or the most inhumane. What we need are changes that lessen the stakes of the conflict, that begin to reconcile each sides’ competing interests.

Both Israelis and Palestinians need a pathway toward getting at least some of what they each want: humanitarian aid, economic development, and greater freedoms in Gaza, assurances of security for Israelis. But getting there will probably require decreasing the influence of the extreme voices on either side of the Gazan border fence, those partisans that see anything short of total victory as a moral outrage.

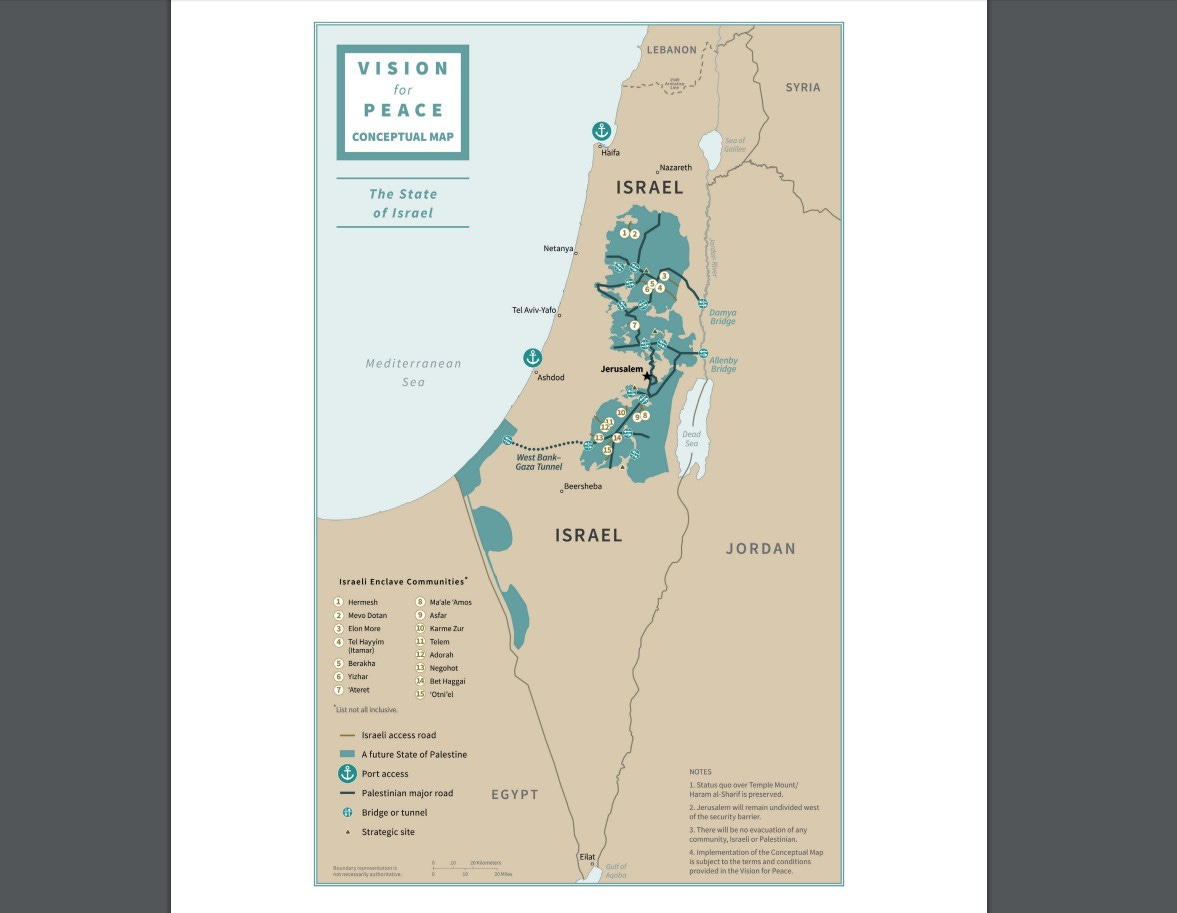

In any case, too much brainpower is wasted in trying to deduce the perfect outcome for Israel-Palestine, an impossible rationalistic adjudication of who deserves what land. Or it is spent attempting an unachievable logical determination of the appropriate proportionate response to either side’s recently demonstrated inhumanity. Who knows if a two-state or binational solution is feasible, much less former president Trump’s proposal for opening up the Negev to Palestinian settlement.

What the region really needs is a next step that works for both sides, not endless retaliation. We can look to cases like post-Apartheid South Africa, Northern Ireland, or post-genocide Rwanda not as models for what post-conflict Israel should look like, but as inspiration for how to break away from a horrific status quo. Could Israelis and Palestinians begin to muddle toward workable partial solutions? We can only hope.