The Geriatric Patriarchy's Guide to Baby-Making in the 21st Century

What City Planning Meetings, Twitter Roasts, and Tone-Deaf Policies Reveal About Japan's Demographic Crisis

The timing was shrewd. The mayor had just delivered his opening remarks outlining his vision of high-end, labor-intensive industries and the future in Japan to the 30 or more of us General City Plan Committee members assembled that night at the restaurant, a low-lit place with traditional wooden finishings, jazz on the speakers, and young waiters weaving between tables.

This was our group’s first informal gathering after three formal meetings at city hall—a chance to finally engage in nomunication with each other. This playful neologism blends “communication” with the Japanese word nomu, to drink. Following custom, the event started at 6pm sharp with youngest/lowest-ranking person pouring out beer from large glass Asahi Super Dry bins into the smallish glasses at each place setting. There it had warmed while the mayor talked. Now only one thing separated us from the much-desired boozy loosening of inhibitions—the toast.

Other important city officials were in attendance, all male. So I was surprised when they called up a female committee member, a senior administrator at one of the local universities, to give the toast. Moving to the head of the room, she commanded our rapt attention, and used it to say something important; something that probably couldn’t have been said at one of our meetings, and even if it was, it wouldn’t be heard in the way she was going to make us hear her now.

This is an important principle of nomunication.

Usually, the toast is nothing more than a check that everyone is holding their glass, an admission of one’s incompetence at giving speeches, followed by a loud Kanpai! and cheers all around. On this occasion, however, after giving thanks to the city for the opportunity and the rest of us for our hard work, she struck right to the heart of our committee’s primary focus: Depopulation—of the city, as well as the country—and what to do about it.

The Crisis Hiding in Plain Sight

We committee members have all agreed to a 3-year term of quarterly meetings to discuss and help generate a 10-year plan for the city as a whole. That timeline means the next mayor has to follow our plan, and its “general” scope covers everything from garbage collection to the availability of child-rearing facilities to tourism initiatives. But from the first meeting the city managers who organized the entire thing made clear that the primary issue, the one affects all others, is depopulation.

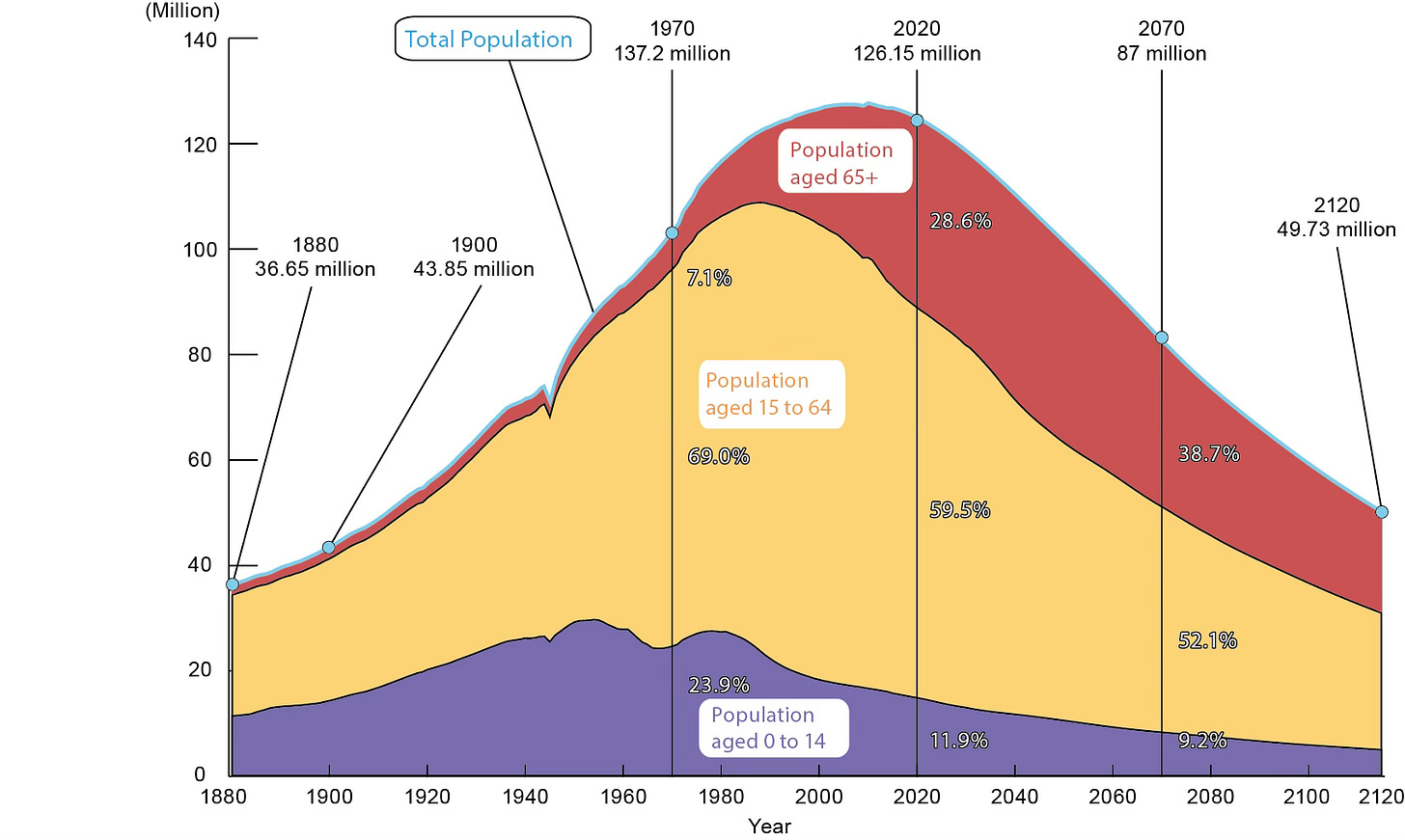

Japan’s depopulation problem at a glance

As for what to do about it, our Committee had discussed the issue at length now three times. Despite a mix of members that I would call “highly diverse for Japan”—including everyone from the locally famous radio host and head of the city hospital to CEOs of prominent regional corporations and, of course, yours truly—it seemed like our proposals were defaulting to more of the same. This boiled down to increasing the existing financial incentives for childbearing (e.g. raising the city contribution to the child tax credit, etc.) and perhaps adding a PSA campaign.

Most concerningly, the more influential members of the committee (chairman of biggest bank in town, for instance) seemed to be successfully convincing city officials that without slapping some KPIs on the problem, it wouldn’t be clear whether the subsidies were really turning into more babies per annum.

So I was stunned and overjoyed when the woman giving the toast used the opportunity voice concerns that we apparently both shared. She grabbed the Japan’s male gerontocracy “by the beers,” let’s say, and pulled in tight to say,

I want to remind everyone that a society people want to bring children into is one in which they feel cared for, respected, treated with dignity—not one in which they are reduced to a number and burdened with the expectation to bear children because the city’s future tax revenues are projected to otherwise plummet. Young people already report feeling overburdened. Adding to their burdens is likely to backfire.

Paraphrasing, allow me to translate the cultural subtext as I heard it:

If the old men (who basically still run most everything in Japan) in that room were planning on placing the blame for depopulation on young women—a standard move in Japanese politics at the national level—then she wouldn’t bother shoving her foot up their asses, because their heads are already up there.

She let the tension hang in the air for a powerful moment, then cut straight through it with a hearty Kanpai!

This is another important principle of nomunication.

Simple in theory, complex because social

It’s not only male Japanese politicians who reduce their country’s depopulation problem to a single, all-too-simple reason: Women aren’t having enough babies. This is, undoubtedly, the proximate cause. But unlike problems in physics or math, reducing social problems to their constituent parts does not always shed light on acceptable solutions.

We might say the proximate cause of “child hunger” is that kids are not getting enough food. Unlike quantum gravity, for instance, the proximate solution here is not too mysterious to understand or difficult to implement: Just fill kids’ bellies. But a policy of telling Moms to cook bigger dinners is an unacceptable solution because it fails to address—or even acknowledge—the deeper causes of why kids are going hungry in the first place.

Most social problems work this way. Yoshitaka Sakurada, a member of the House of Representatives, learned this lesson back in 2019 when he told his supporters: “The number of women who don’t feel a need to get married is rising … I would like to have you all ask your children, or grandchildren, to have at least three children each.”

The throttling on Twitter was swift and to the point:

“Shut your mouth, Sakurada.”

“He doesn’t get it at all. It’s not like people aren’t having kids because they don’t want them. He doesn’t understand that in today’s world, it’s incredibly difficult from a financial, psychological, and energy standpoint to raise three kids.”

“Please make a society in which I can have three kids.”

As the first comment implies, he just doesn’t get it. What, exactly? The second comment lays it out: That having children is a complex decision with many interdependencies across all the facets of one’s life, not a simple matter of fertilizing an embryo. Moreover, in today’s world, where the rational evaluation and optimization of one’s opportunities is prioritized by a tech-obsessed society while uncertainty across economic, political, military, environmental, psychological domains is ceaselessly amplified by rapid technological change, it’s a tough calculation to make.

Moreover, in today’s world, where the rational evaluation and optimization of one’s opportunities is prioritized by a tech-obsessed society while uncertainty across economic, political, military, environmental, psychological domains is ceaselessly amplified by rapid technological change, it’s a tough calculation to make.

Whose fault is that? As the third comment makes plain, Sakurada had forgotten his own role in the complex web of causation surrounding the national birthrate. As a democratic politician with a pro-natalist position, it’s his duty to create the society described in that epic toast.

The Gerontocracy's Tone-Deaf Solutions

Sakurada later apologized, and to be fair, his sentiment isn’t uncommon among older Japanese people. Sakurada was hardly the first or the last politician to put his foot in his mouth that way. My father-in-law has said the exact same thing to me, and I know he meant well.

No one knows what to do, so a lot of spaghetti gets thrown at the wall. My favorite was the government’s short-lived “Sake Viva!” campaign to encourage young people to drink more alcohol during the COVID-19 shutdown.

Hoping to both revitalize the economy and encourage some new pregnancies, this perfectly demonstrated how the Japanese gerontocracy is completely out of touch. Young Japanese people were turned off, with even sake critics condemning the campaign as crass, and Western media outlets had a field day with the story.

Still, I get it. The old guys in my village complain that young people just don’t drink like they used to. It’s basically like, “Hey, you uptight kids, why don’t you have some drinks, chill out, and … maybe *wink, wink* see what happens, you know?” Alright, alright, ojiisan.

I can even give a charitable reading to the conservative MP who, in a fit of hysteria, said women over 25 should be banned from ever marrying, and that women over 30 should be forced to have hysterectomies. A policy guaranteed to backfire, sure. But I think his hysterics were probably just an extreme expression of the current zeitgeist.

Japan is in a Don’t Look Up moment. A recent Prime Minister said in 2023 the depopulation problem is so severe that the nation is “on the brink of not being able to maintain social functions,” adding that the time to act is “now or never.”

What irks us youngsters is the superficiality of their analyses.

Global Trends, in the Japanese Style

Falling birthrates are a part of a complex constellation of modern social problems that include plummeting rates of marriage and sex, as well as rising rates of isolation and depression. The suicide rate has actually been dropping in recent years, but remains high. When these trends were first identified in Japan decades ago, they were thought to be somewhat unique to the island. But now they are global, endemic to most all developed nations. It was by historical accident that the “silver tsunami” hit here first.

Culture still matters in how these demographic trends and social problems play out. And Japan is still Japan. Here, these issues are entangled within the bigger shifts happening as the sinews of traditional Japanese society give way to the acid bath of modern individualism, with its package of (mostly Western) technologies and concepts. This probably gives the dynamics of depopulation here a Japanese flavor, and things will likely unfold differently in nations that have already been thoroughly atomized by neoliberalism, such as the UK.

That said, the general tendencies are now global, and real-world examples of nations with such advanced depopulation remain few. So it seems worthwhile to make some sense of the Japanese case.

Beyond the data: Numbers don’t tell you much

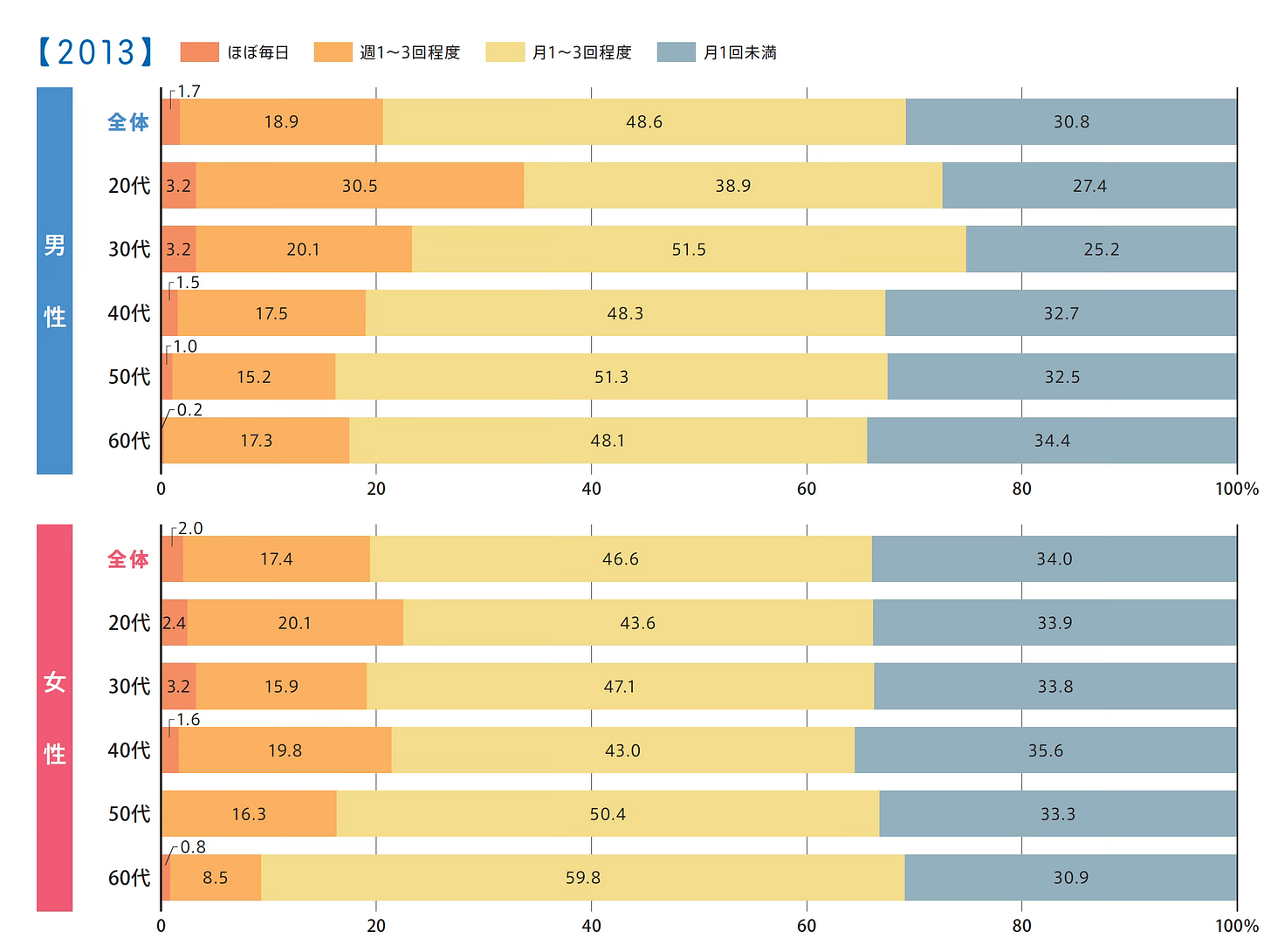

You can find any number of articles on this topic packed with data about Japan’s disconcerting social trends. Japanese institutions remain robust here and the data can be mostly trusted. But after reviewing a fair amount of this material for the City General Plan Committee, my impression is that quantitative studies don’t really tell you much beyond the fact that decline—of birthrates, marriage, sex, of life itself!?—is happening, and here are some numbers to prove it. For example, the JEX Japan Sex Survey 2024 shows that sexlessness among all age cohorts from 30 to 60 year-olds has basically doubled since 2013.

Comparisons of sex rates for 2013 and 2024 by gender and age cohort.

Blue = Men, Pink = Women. 4 point scale from “almost every day” to “less than once a month” (sexless).

This is surely an important finding. As for why, though, your guess is as good as theirs.

Semi-qualitative survey data can help shed some light on these raw numbers, but it suffers from two problems; one specific and one general. First, a cultural emphasis on personal privacy makes Japanese people notoriously difficult to survey. It’s a common joke among clinicians and social scientists that any response on a scale from 1 to 10 will cluster right at 5. The subsequent data is typically so uninformative it undermines the research design, but often gets used anyway.

As the Japanese would say, shoganai—literally, “nothing can be done [about this].”

The second, more general problem with survey data is inherent to all complex social issues, including depopulation. In probing these issues, we run up against the limits of human cognition—our limited ability to know the world, and ourselves.

You can ask someone why they aren’t having kids, and they can give you a reason. Or like Commenter No. 2 in the Twitter roast of Sakurada, they will give you a bunch of reasons. These will almost certainly be other complex social problems, like the poor economy or the impending climate catastrophe.

I think we do this because we don’t really know the reason why. As Nietzsche and more than a few other psychologists have shown, the reasons we give for any particular decision are often post-hoc rationalizations of decisions already made at subconscious—and thus sub- or non-rational—levels of cognition.

Our rational mind doesn’t have access to the “actual” reasoning process that led us not to have any kids, but it can create any number of reasons why having kids is too much to deal with right now. So surveys have to be taken with a grain of salt.

Don’t get me wrong. Quantitative data can of course be helpful. It’s good to know what is happening and how, but if policymakers are going to do something about depopulation, we need a better sense of why it is happening.

Next: The Human Face of Japan's Demographic Crisis

In my next post, I’ll to try to get at the why by taking a qualitative approach to depopulation dynamics. I’ll introduce you to a cast of characters distinctive to late-modern Japanese society. You’re probably familiar with the hard-working “salaryman,” and may have heard of the extremely-introverted hikikomori. I’ll examine these and other less well-known figures—like the ambivalent “careerwoman” and the frustrating “freeter”—as examples of adaptations to the conflicting pressures of collectivism and individualism. This might provide a better lens on the complex problem of depopulation than another quantitative report on falling birthrates.

Headlines about grandparents dying alone, skyrocketing rates of sexless marriages, and adult diaper sales outpacing childrens’ might seem foreign or exotic as maid cafes and square watermelons to us now, but the social dynamics creating these phenomena are at work almost everywhere. The flavor might not be what you’re used to, but it could be a taste of what’s to come in your own neck of the woods.

nomunication this needs to be globalized! Also the Japanese should learn from another island nation : Jamaica 🇯🇲 pass the Dutchie on the left hand side 😎