Part III of the series “Innovation’s Elon Musk Problem”, see Part I and Part II.

Asked to imagine an innovator, many people would envision something like Iron Man’s Tony Stark. Various Marvel films depict Stark as having near superhuman intelligence, able to single-handedly master arcane fields of knowledge and produce new technologies at lightning speed. But these are unreal intellectual qualities that, even more so than the fictitious technologies, make the films works of fantasy. Our tendency to see innovation as a product of individuals blinds us to the important realities of technological change. And, as we’ll see later in this series, that tendency lies beneath many of the pathologies of our current system of innovation.

When looking back on the history of technology, there is a tendency to imagine advancements as happening in leaps and bounds, the result of pioneering work by “great men.” Long before Elon Musk graced the cover of magazines such as Wired, Time, and Rollingstone, newspapers were touting Thomas Alva Edison as the “Wizard of Menlo Park. Journalists strove to cover his inventions long before they actually worked.

It was the start of a cultural pattern that was only fully realized with later inventors such as Buckminister Fuller, whose fame came more from the alluring futurism conveyed by their designs than the practicality of their actual inventions. Fuller presented his 1933 Dymaxion car prototype as a step toward a flying car. While it could turn on a dime and boasted a high top speed and impressive fuel efficiency, it handled poorly and became dangerously unstable in windy conditions.

The “great man” trope is deceptive, obscuring a reality that is far more messy, diverse, and incremental. Even though Thomas Edison gets credit today for “inventing” the light bulb, similar technologies existed at least 40 years before his invention. What Edison really accomplished is the creation of a relatively inexpensive, reliable, and commercially viable bulb, and only with the help of a large team of technologists that worked in his laboratory. One of the biggest advances to “Edison’s” technology came from Lewis Latimer, an African American renaissance man who invented a carbon filament that was more durable than Edison’s. Only a few years earlier, he had helped Alexander Graham Bell patent the telephone.

Serbian-born inventor Nikola Tesla, despite the common belief to the contrary, was actually not much different from Edison in this regard. Although he popularly receives credit for inventing everything from AC motors to radio, most of Tesla’s creations either built upon previous innovations or were cases of simultaneous discovery. And it is important to note that Tesla’s patented inventions had to be made commercially practical by still other engineers funded by people such as George Westinghouse.

Despite prevailing tales of deceit, Thomas Edison’s genius wasn’t really about “stolen” ideas from talented engineers. The same logic would implicate Tesla in “stealing” from Edison, by taking out a patent on a lighting system derived from work he did at Menlo Park. Rather, Edison understood that innovation is not a singular event, not the fruit born of the labor of the lone genius, and that it was a collective slog. One of his best remembered quips was that “genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.”

More importantly, Edison grasped that successful entrepreneurship meant building systems. He made money because he paired his inventions with several others: electrical generators, plants that house them, power lines, a system of distribution, and other creations that use the same electricity. And it took an entire research park, filled with teams of skilled engineers and financiers, to work out how to solve the problems necessary to get his electrification system to work.

Real-life innovators are much more like Harry Potter than Tony Stark, someone who is probably moderately above average in most of their personal qualities, apart from sheer determination. At seemingly every turn in J.K. Rowling’s books, it is help from Harry Potter's friends and happy accidents, rather than his genius or talent per se, that enables Potter’s success. Yet it is Harry who we remember as the hero.

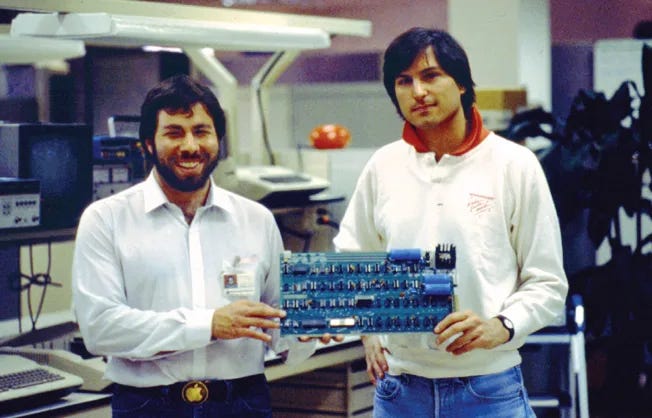

Innovation history is Potter-esque: good luck and fortuitous connections have often made the difference. Microsoft came to dominate the operating system market because IBM’s then-chairman John Opel knew Gates’s mother and decided to do business with “Mary Gates’s boy’s company.” Jeff Bezos started Amazon only after serving as senior vice-president of a hedge fund, which no doubt helped with securing investment. Steve Wozniak admits that Apple’s founding in a garage is mythical, as drafting, soldering, and putting together Apple Computers happened in his Hewlett-Packard cubicle. And their success was aided by Mike Markkula, a 33 year veteran of the semiconductor industry, who brought much needed credibility to their start up, similar to the role Greg Kouri later played for Elon Musk.

Individuals alone don’t cause technological change. It takes networks of expertise, infrastructure, and finance all working together. Innovation is far more complicated than hero-worshiping tales of long nights in labs and underappreciated technological mavericks.

But why does it matter if innovation doesn’t happen like we tend to think it does? Why should we care if the story of Elon Musk that suffuses the media or draws venture capital to his start-up businesses is more myth than reality?

From driving the development of electric cars to SpaceX becoming the company to send the next Americans to the moon, Elon Musk hasn’t actually revolutionized the technological landscape, even if he has been a catalyst for change. We need to understand how technological advancement really happens, if we are to imagine how innovation could be even better.

I liked the brevity of your info and the giving credit where credit is due.

Im not sure what you expect to gain from correcting the narrative on this. People who actually innovate understand the process is messy and contingent. There is place for individuals. There is a place for teams. There are generalists and specialists. Someone needs to look at the bank accounts and resolve conflict. And the whole process is predicated on a billion things you'll never understand, much less take credit for.

The public is going to believe whatever they want about technical progress, and the "great man" narrative sells. Resaerch isn't free, so I just live with it.

My pet theory is all this is monkey-brain. We instinctually expect the top of a heirarchy to "master" everything below it. The problem is that someone needs to be at the top, but modern organizations are so complicated that its impossible to master any of it, much less the whole thing.

This is obvious with Musk because he has top-spot in an impossibly broad array of very complex companies. Moreover, he's hard to cirticise on all the normal capitalist stuff, since he provides real benefit and isn't obviously optimizing for short term capitgal gains at the expense of labor, the enviroment, etc. So all we got is "he doesnt deserve it" lol