The NIMBY Problem

Overcoming Albuquerque Rapid Transit's Political Barriers

The NIMBY problem. Anyone who has been to a town hall on new developments, whether that be dense infill housing, new transit, or affordable housing has seen this in action. Inevitably residents come out in droves saying things like “I am in favor of affordable housing, just not here.” Not In My Back Yard, that's what NIMBY stands for and it's pretty descriptive. Whether they want to “maintain the character of the neighborhood” or are “concerned for the safety of neighborhood children” the common pattern is that they oppose local changes. The problem they pose is that NIMBYs can block broadly beneficial and popular new developments.

A vocal minority preventing policies that benefit the community as a whole is clearly a problem for democracy. Authors like Matt Yglesias have pointed out that when angry people start showing up, whether in the streets to protest or to city council meetings, that isn’t what democracy looks like. That's actually what a failure of democracy looks like. Those people are there because all the processes of our democracy prior to that point have failed. This means that public meetings where angry NIMBYs show up to oppose an otherwise broadly beneficial development aren’t actually very democratic in and of themselves.

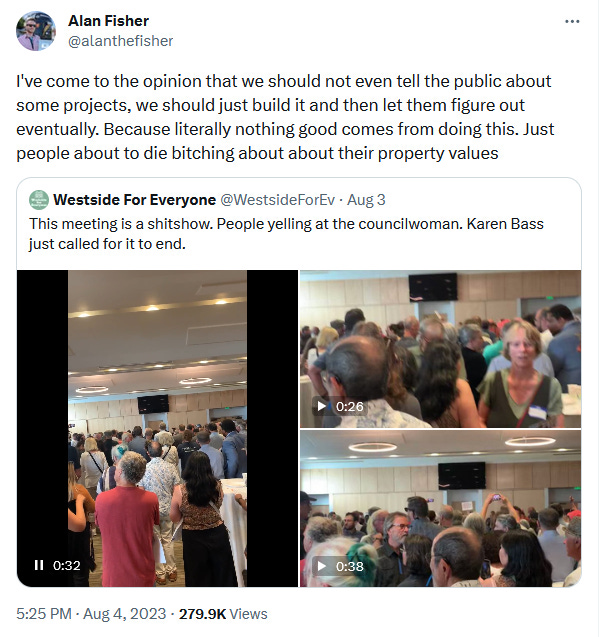

But Yglesias, and many others, get the alternative wrong. Yglesias argues that decisions made by our elected representatives are already democratic. We elected them after all. We don’t need to have yet more meetings to make decisions already decided via elected representatives. Prominent transit and urbanist advocate Alan Fisher, of The Armchair Urbanist, suggested on twitter that we could avoid shit-show public meetings by just not telling people about some projects.

Fisher’s channel is entertaining and informative with excellent content, and he’s right that these sorts of public meetings are very often a shit show. But what both he and Yglesias get wrong is that neither relying on elected representatives or technocratic city officials solves this problem.

Albuquerque Rapid Transit (ART) was approved 7-2 by the city council, and, as I’ve shown earlier in this series, was mostly a success from a technical standpoint. Neither of these facts prevented coordinated campaigns to stop the project, nor did they prevent the project’s massive unpopularity.

That’s right, it's another post about ART! You can read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 4, but if you’re all caught up, you might now be wondering: what, then, do we do about the NIMBY problem?

Building constituencies

Looked at with the benefit of hindsight, ART just doesn’t seem that out of the ordinary as far as transit projects go. Certainly, it was not worthy of the almost exclusively negative press it got, or its vast unpopularity. Opposition started with the small businesses that would be affected by its construction. Their opposition was fierce, including a suit to stop the project altogether. So, as advocates for better transit we have to ask, why was their opposition so fervent, and is there any way around it?

The answer to a lack of democracy is more democracy, not less. Political scientist Edward Woodhouse argues that for democratic deliberations to be effective, they have to be done early, while the technology in question is still malleable enough to change. From the perspective of transit advocates, we’ve likely experienced opposition enough to know that when you’re arguing at city council meetings you’ve already lost. But from the perspective of NIMBYs, it is no doubt frustrating to see a proposal on the table and your only choices seem to be either accept it or reject it. The process must start earlier. Is it any wonder, then, that opposition is the default position over negotiation?

Supporters of better transit, thus, need to do two things. First, they need to marshal positive constituencies to be advocates for new projects. Second, they need to avoid creating negative constituencies who do things like sue to stop the project. Both can be accomplished by reaching out to the relevant groups for deliberation as early in the process as is feasible.

Positive Constituencies

Right before contractors were going to break ground on ART, a collection of property owners and local business owners led by the restaurant association sued the city of Albuquerque to stop the project. This suit led to the impression that local businesses were against ART, but that isn’t true.

While some businesses closed, other new ones opened, such as Frenchish and My Vinyl Offer. Those businesses opened in anticipation of the customers an operational ART would bring. That certainly isn’t opposition. Owner of Blunt Bros. Coffee, Dave Rodriguez, saw an improvement in his business, attributing it to slower traffic allowing people better awareness of the businesses they otherwise just cruised right by. John Gonzales, the owner of 2Gs Bistro downtown, concluded that, even though construction did make business worse, ART makes things better. He supports more BRT routes which he believes will bring even more customers into the mix. Hardly the unified front of local business owners against ART.

We also know that ART brought in a lot of new development. Some of it began even before ART was finished. For instance the $95M project across from Presbyterian Hospital, or the redevelopment of the old Sears building downtown at 5th and Central. Not to mention the hundreds of new housing units built all along central. Certainly the business owners planning on occupying these locations, the construction companies building them, and the developers investing hundreds of millions of dollars in them were in favor of keeping ART.

And why should we focus so much on business owners? An explicit goal of ART was to provide valuable transit connections to underserved communities in the International District, colloquially called “the war zone.” Certainly there must have been some people in that area happy to be getting public resources directed to their needs!

So the question is: where was the opposition from these groups to the lawsuit? Where were the op eds from these people to balance the press given to the restaurant association? Why wasn’t there an advocacy group balancing the opposition from groups like “Make ART Smart”? Despite opposition being far from universal, there didn’t seem to be the same kind of organization among proponents to make sure ART happened, despite some very clearly vested interests! Could this have been avoided if the city had reached out to these groups before starting the project?

I suspect yes. Let's look at another example to see how. Portland is fairly well known for its downtown streetcar network. But streetcars are more expensive than BRT, and not really any better at moving people. So how did they manage to spend more money on a less efficient transit system? By working with developers! The city negotiated a development agreement with landowners in the areas where they wanted to put the streetcars. In exchange for high quality public improvements, like the streetcar, developers would commit to building incrementally increasing densities.

The city also created a local improvement district, through which land owners contributed about $20M of the $103M total cost. We know Albuquerque already identified increased development as a reason for building ART. If the city had directly approached the developers and landowners they were targeting with ART, it's possible they could have negotiated win-win deals that would have also garnered more active support from those groups, or which may have been seen in a more positive light by citizens.

Likewise, we should consider how the city approached the community in the International District. On the one hand, the city worked with the Federal Transportation Administration to try to balance providing services to a historically underserved area with the displacement that often occurs when such areas do get new development. But when we examine the recommended steps it revolves around yet more support for area small businesses and “develop messaging tools that would best support ongoing outreach.”

But outreach and messaging is one-way. It isn’t engagement, and it isn’t any more democratic. Community leaders in the area have already been active in fighting for the safe streets in the area. There are already nonprofits operating in the area that the city can work with, such as the Albuquerque Indian Center or East Central Ministries. Engagement is what builds constituencies, not messaging.

The popularity of a project like ART is often treated like some sort of immutable characteristic. But in reality popularity is not entirely out of the control of local governments. Approaching and engaging with different interested groups can turn those groups into positive constituencies. I have seen urbanists bemoan the most common form of public engagement, open public meetings and city council meetings, as just another opportunity for NIMBYs to veto projects proposed by already democratically elected representatives.

And they’re right. But I also think they’ve struggled to suggest an alternative that is still democratic. But such open meetings, happening long after there is any option aside from approve or outright oppose, are themselves not very democratic. When relevant groups of interested constituents are brought into deliberations early enough to actually influence the final configuration of the project, they can be transformed into positive constituencies. This is how a project like ART, which had so many positive outcomes, could have also been much more popular.

Negative Constituencies

On the other hand, ART succeeded wildly in building no end of negative constituencies. Too bad that wasn’t the city’s intention. The city council proposed two bills that would have required putting the project to a referendum vote. Both failed. Even the responses I’ve gotten to this series have been filled with continued local negativity about ART!

But the most notable example of a negative constituency were the two lawsuits attempting to stop the project. The lawsuits alleged that the city and the Federal Transportation Administration (FTA) violated the Federal Environmental Protection Act as well as federal and state historic preservation laws. The FTA granted Albuquerque an exemption to assessments in both cases, and the lawsuits alleged that these exemptions were unlawful. The lawsuits were brought by a coalition of business and property owners along Central Avenue that were to be affected by the construction.

Both lawsuits were eventually dismissed, but the issue at hand is that such a coalition was able to form in the first place. Why, when the city council voted 7-2 to go ahead with the project, was there such coordinated opposition?

Much like with positive coalitions, negative coalitions are the result of an inability to engage relevant interest groups early enough in the process. Let's take the Central Loan Fund as an example. In the previous installment of this series, I lauded the fund as a creative way to help businesses despite the substantial legal barrier of the Anti-Donation clause in the state constitution. But that isn’t how local businesses saw it. They saw it as too little too late. Many also thought the maximum loan size of $15k wasn’t enough. And not all of the assistance from the program was monetary. Some came in the form of business advising, or things like free web design training. While some businesses took advantage, others felt insulted. They didn’t feel like they needed advice. They needed customers, and the reason customers weren’t coming was pretty clear.

The city did not come up with a solution to the harms the project did to businesses until a year into construction (near when the project was originally scheduled to be completed). Worse, they came to business owners with an already formed policy plan. While members of the non-profits running the fund were reaching out to businesses, outreach isn’t inclusion. How much money did businesses expect to need to weather construction? What non-monetary support did they actually want? Better yet, were there any changes to the construction plan that would have eased the pressure on local businesses without ballooning the costs of ART?

Albuquerque should have approached businesses along Central Ave. prior to breaking ground, when there was still some influence they could exercise over the policy that would aid them. Perhaps that would have at least fomented enough disagreement among them as to prevent a coalition for a lawsuit, and help undercut the refrain that ART is anti-business, which still haunts the story of ART to this day.

Lessons on NIMBYs

ART has a lot to teach us about how more democracy, not less, is the key tool against the seemingly intractable problem of NIMBYs. We already know that NIMBY dominated public meetings aren’t democratic. They are merely opportunities for a minority to effectively veto projects that have a broad benefit. When angry NIMBYs show up to a public meeting, that's a sign that democracy has failed.

But rather than give up on democracy, I think we should make it stronger. ART shows how relying on elected officials or ramming through projects can backfire. Despite the eventual success of the project, it was, and still is in many circles, immensely unpopular. But it didn’t have to be.

Constituency building is the beating heart of democracy. By the time the public meeting comes around, it should be perfunctory. The city should already know who is on board, who is against it, and should already have hashed out a policy that attracts supporters and mitigates opponents by directly working with those very groups to develop it. Public meetings can, indeed, be destructive. But they aren’t democracy. Public meetings are more a check on the adequacy of constituency building. A city that puts in that initial work to build positive constituencies and mitigate negative ones will have smooth public meetings, better transit and more urban investment, and do so more democratically to boot!

Very nice article.

I read Ed Rendells memoir awhile ago, and he pointed out that the reason consideration is preferentially given to select parties is simply because they are more engaged/lobby harder. Like when he was mayor of Philadelphia he had to renegotiate the cities union contracts because they were bleeding it dry with objectively ridiculous compensation and protections. The reason it got that bad was because Unions leaders jobs are to go lobby, and if you full court press the city for decades you will gradually extract more and more.

He had to go out and drum up support from the rest of the population to actually make progress, because they needed to weather garbage collector strikes and whatnot. He gave an anecdote when he was at his kids baseball game, and a union guy came up to him to bust his balls about the renegotiation, but some other guy ended up coming to his aid by complaining that his salary was half the city employees for more work and he was sick of it. That's when things started to change.

The squeaky wheel gets the grease, and politicians are human. So if you scream in their faces you'll get what you want since most people aren't strong enough to push back (ie. to relatively disenfranchise them on behalf of other constituents)

We expect elected officials to act undemocratically for the greater good, but in practice they can't do that so you need to ensure balanced engagement.

The community engagement itself was put in through a democratic process - previously, developers run rough-shod over communities and popular mayor/councils were elected to create the community engagement process.

Consider: If this is taken away, NIMBY mayors/councilors themselves might be elected. It happened in the 80s when these laws were introduced, it can happen again.