Gas stoves have recently become the center of the latest culture war. Since a Consumer Product Safety Commission commissioner carelessly mentioned banning them in light of their potential hazards, Republicans have sounded the alarm that the feds were coming for people’s kitchen appliances. Democrats have moved to deny that a gas stove ban was in the works, but nonetheless concluded that eliminating gas stoves would be in everyone’s best interests. A group of city and state attorney generals have since called for federal action.

The trouble with the risks of gas stoves is the same as it is for a whole host of modern dangers, like microplastics or climate change. The hazards are uncertain. It is hard to really know how much risk we actually face. Scientific studies can be helpful but not totally determinative. And the unknown unknowns are anyone’s guess.

As others have pointed out, the studies connecting gas stoves to childhood asthma are fairly weak. They suffer from small samples, confusing conclusions, among other problems. Are the stoves really the cause or are we see some other factor at work that happens to correlate with owning a gas appliance? How much does the typical stove emit and what kind of dose do residents get? Roger Pielke Jr. points out that studies find that the emissions from cooking oil are a magnitude higher than from the stove itself. So, it is possible that attention on how our stoves are powered distracts us from a much bigger cause of indoor air pollution.

Banning gas stoves is high stakes politics.

Still, the case against gas stoves seems commonsensical. They leak NO2, which can exacerbate asthma, and methane, which is a greenhouse gas. Combined with the drive to reduce fossil fuel usage more broadly, there’s a reasonable case that eliminating gas stoves would be prudent in the absence of clear evidence.

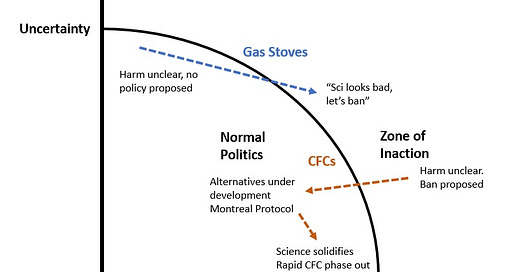

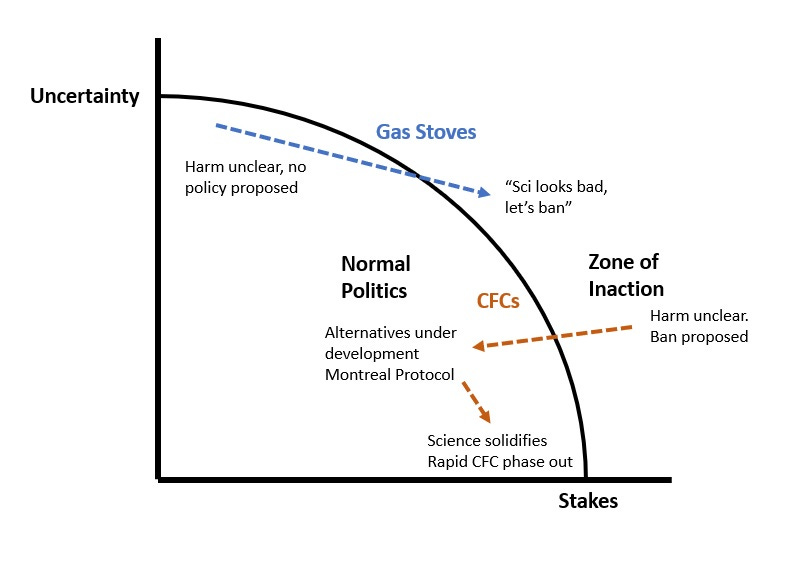

But the move to ban isn’t actually all that reasonable if we take a broader view of how we have tackled similar issues in the past. When faced with a complex problem involving human or environmental hazards, we have been most successful where we have lowered the stakes of action, not raised them.

One example is the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to reduce and eliminate the use of CFCs thought to be harming the planet’s ozone layer. What few people remember about the Montreal Protocol is that the science was still very unclear. Agreement was possible because alternatives to CFCs were already in development and could be had at comparable expense (appliances use a tiny amount of refrigerant). In other words, what looked to be a costly solution (i.e., a ban) really had fairly low stakes. Even chemical companies soon recognized that moving quickly on alternatives was in their own interests.[i]

This is why banning gas stoves is sure to be a political debacle. Sure, there are alternatives to gas stoves. But regular electric ranges are slow to warm up and cool down in comparison to gas, and induction stoves are generally much more expensive. Even then, if your house doesn’t have an unused 40-amp circuit available with thick wires running to the kitchen, you will spend a lot on an electrician. And, while nobody really cares whether their AC runs on CFC-based refrigerants or not, many people have a strong attachment to cooking with gas. Banning gas stoves is high stakes politics.

So, what to do? Ongoing scientific study may reduce the certainties considerably. But, in light of our experience with similar controversies, reducing them enough to make bans politically straightforward seems unlikely. Induction stoves might become cheaper, but the electrical work required will still make the switch expensive. That said, home developers don’t care and will probably ditch gas stoves in their builds.

Overlooked in all the cultural waring is the option of simply increasing code requirements for kitchen ventilation. By taking a technology neutral approach, we can improve indoor air quality without evoking the same high stakes. And it might actually be more beneficial, given the evidence that cooking itself is the source of a lot of emissions. Home builders and consumers can choose how to react to the standards. If a gas stove ends up needing a more onerous investment, people will be forced to decide for themselves whether gas cooking is really worth it.

But this runs contrary to a long-standing pattern in environmental politics. So long as we think complex problems and thorny political disagreements can be resolved by scientific study rather than smarter policy, we will continue to struggle against political gridlock.

[i] The size of roll played by technological alternatives is disputed, with some arguing against the “myth of technological breakthrough.” DuPont had actually ceased research on alternatives when Reagan was elected, anticipating less regulatory pressure. They eventually switched gears in response to declining consumer demand for CFC products and recognizing the obvious profitability of being a supplier of CFC-alternatives should the then-proposed Montreal Protocol be ratified. Nevertheless, previous work on alternatives nevertheless changed the character of the conflict, as Dan Sarewitz put, “made it possible to meet the goals of multiple constituencies with conflicting values and worldview.” See Daniel Sarewitz, “Political effectiveness in science and technology,” in Science in the Context of Application (New York, Springer: 2011), 301-316; Maxwell and Briscoe, “There’s money in the air,” Business Strategy and the Environment 6, no. 5 (1998): 276-286; Whitesides, “Learning from Success: Lessons in science and diplomacy from the Montreal Protocol,” Science & Diplomacy, August 10, 2020, https://www.sciencediplomacy.org/article/2020/learning-success-lessons-in-science-and-diplomacy-montreal-protocol.

Great Article,

Gas stoves could be phased out in new home builds by simply not routing gas. The major concern from my POV would be the sudden switch to electric and the strain it puts on the grid.