I wrote a few weeks ago about how the increasing size of personal vehicles acts like an arms race. Individuals all act rationally, buying the vehicles that will best protect their loved ones riding inside. But the outcome is irrational: everyone, including the purchaser and their loved ones, are actually less safe. And of course the consequences are disproportionately large for those outside of cars: pedestrians and cyclists. But I didn’t write this to be some kind of SUV doomer. So what can we do to end an arms race?

The knee-jerk reaction might be to coerce people into making different decisions. I see no shortage of attempts to shame people into compliance on social media spaces. Those of us who are a little more forgiving might instead suggest some sort of educational campaign. Perhaps, if we can just show people the error of their ways we can interrupt this vicious cycle.

Unfortunately, neither of these solutions are likely to work, and for the same reason. Direct intervention in an arms race is an unlikely proposition. In a traditional arms race, it is very risky to try to be the one to stop it. Although the arms race between Germany and Britain directly contributed to the outbreak of WWI, could either side have simply stopped? Britain, as an island nation, relied on their navy to defend themselves. Could they really have afforded to allow Germany to surpass them and leave themselves vulnerable to invasion? And one of Germany’s primary strategies against Britain was to use their navy to disrupt supply lines while maintaining their own access to the Atlantic ocean. Could they have afforded to abandon their strategy?

The same is true with SUVs and trucks. We can scold people all we want about how they are putting others in danger. We can throw tables and charts and pictures about the dangers of SUVs and trucks around, but for most people that isn’t going to be enough to make them accept the risk of being the one outside of the SUV. No, we cannot tackle this problem head on. So how do we tackle such problems then?

Glasgow, Scotland was once considered the murder capital of Europe. A dubious distinction that played a major role in Scotland’s position as the most violent country in the developed world. The city had tried to ramp up policing to solve its problem. But it ran into the same vicious cycle that we might be familiar with in the US. Young men convicted of violent crimes, stemming mostly from gang activity and their role in the illegal drug trade, get arrested and sent to prison. But when they get out, there is little work or opportunity, and so the only way they can make ends meet is back in the gangs that got them locked up in the first place. The more stringently Glasgow policed, the worse the problem became.

But in 2005, the city started the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU). The goal was to address the problem from an entirely different angle. What if, instead of punishing people after the fact for violence, the city treated violence like a disease and focused on prevention? The VRU took a multifaceted approach. They brought in people whose lives had been destroyed by violence, men who had been permanently disabled in the prime of their lives and mothers who had to bear the unspeakable pain of having to bury their child, to schools with at-risk young people to make clear the consequences of violent gangs. The VRU also includes an employment program, where people convicted of violent crimes can have guaranteed employment for 12 months, along with psychological and career counseling to help them get back on their feet. Researchers also identified symptoms, or precursors, to violent crime, which they then worked to address. For example, childhood abuse makes one much more likely to wind up in a violent gang. So the VRU started a mentor program at schools with students at the highest risk of abuse. These mentors are often also former gang members and victims of abuse themselves and can help students deal with what has been done to them and assist them in accessing state resources.

The VRU has been highly effective. By 2018 violent crime in Scotland went down by more than half since they began the program. Violent crimes in Glasgow itself went down by 37%. By trying to address the underlying issues that lead to violence rather than attack violence head on with traditional policing, Glasgow, and Scotland as a whole, have now become less violent than either England or Wales.

Breaking the vicious cycle of the vehicular arms race will also require us to address the problem from a different angle. We’re going to have to get at the root causes of traffic violence just as Glasgow got to the root causes of gang violence.

One way of looking at the problem is through the lens of inherently safe design. Pioneered by the chemical engineer Trevor Kletz, he suggested for chemical plants that “what you don’t have can’t leak.” That is, if something is unsafe you design to minimize its use. We might ask ourselves, what kind of transportation system could we design for our cities that would make people not want to use cars in the first place?

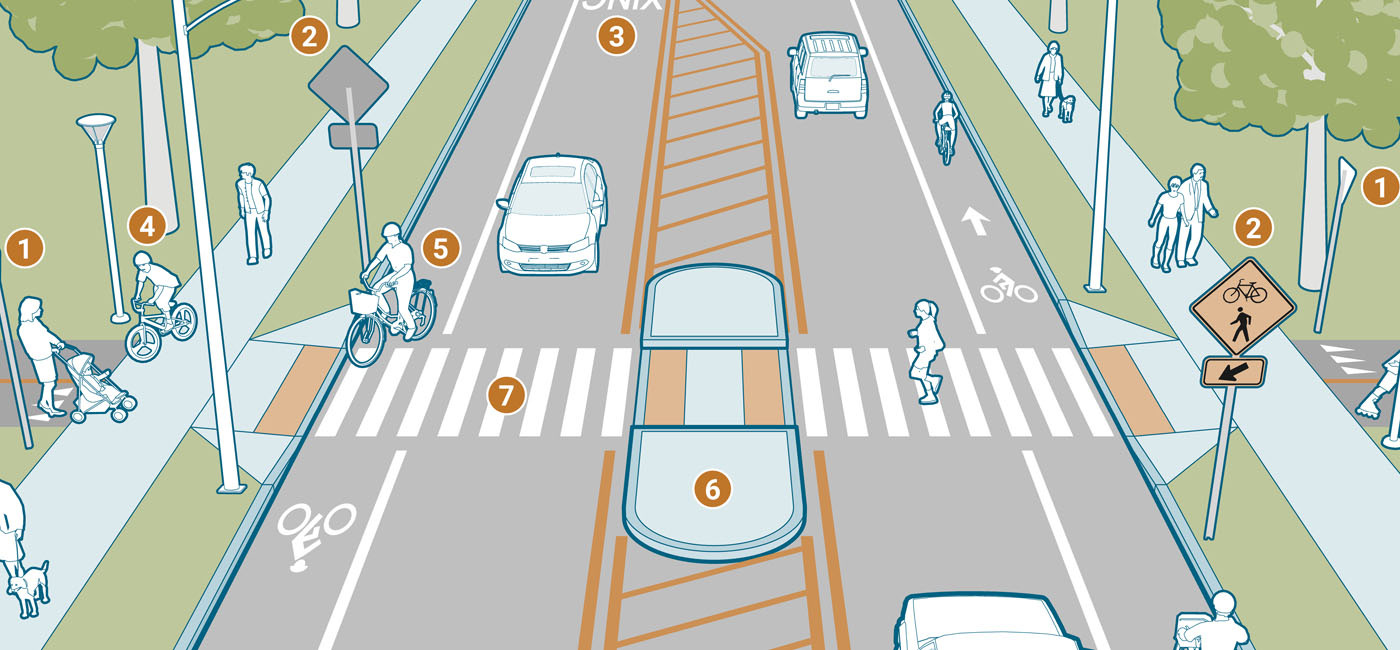

What if our cities prioritized public transportation instead of personal vehicles? We know what makes people want to use public transit. If it connects the places where people live to the places where people want to go, to destinations, and frequently enough that it isn’t necessary to check time tables for most trips, then people will use it. And even relatively inexpensive transit can dramatically increase street safety. Albuquerque Rapid Transit dramatically reduced traffic violence along Albuquerque’s busiest transportation corridor. It also reduced the total number of car trips. And thats just Bus Rapid Transit. Wealthier cities which can afford various forms of rail may be able to do even more.

The same could be done with bicycling infrastructure. Building a complete network of protected bike infrastructure, like multi-use paths, hardened bike lanes, or slow mixed use streets will make it easier for people to choose to bike to nearby locations rather than take a car. Just like safety concerns lead people to buy bigger SUVs and trucks, they are also the main reason people avoid cycling. Building protected bicycle infrastructure can be as easy as switching existing bike lanes and on-street parking. But even using bollards, concrete separators, or raised cycling paths are relatively inexpensive compared to other transportation infrastructure. Plus, people who cycle to their work actually enjoy their commute. A nice little extra bonus.

Walking is equally as important. Zoning cities so that they are more dense and destinations are closer to housing means that walking becomes increasingly convenient. Even folks like me who live in the suburbs don’t drive to visit their neighbor down the street. So if more stuff was just down the street, people would just choose to walk instead of drive all on their own. Cities could allow higher densities of residential by default, or they could allow more mixed use commercial and residential zoning. Cities could also change parking minimum mandates so that business owners and housing developers can decide for themselves how much parking they need and avoid over-building for automobiles.

All of these things done together are referred to as multi-modal transportation. When combined with the zoning reforms that facilitate walkability, it can lead to greatly reduced traffic violence. In Japan, these sorts of policies contribute to places so easy to get around that even children can do it easily and safely without adult supervision. Applying these sorts of changes incrementally can reduce both the perceived and actual risks of traffic violence and therefore reduce the incentives to buy bigger and bigger SUVs and trucks. No one in Japan is buying a Yukon to keep their kids safe because they are already safe.

But Japan wasn’t successful just by implementing multi-modal transportation and better zoning. While such a city would be far more convenient than a car-centric one, it is probably also necessary to reduce the convenience of cars. For example, in Japan, parking is neither free nor abundant. Buying a car requires the owner to prove they have a place to park it, and parking spots are expensive. The owner pays the cost of parking whereas in the US those costs are borne publicly. Taxing cars based on weight, rather than or in addition to a gas tax, would also add an extra consideration to buying larger vehicles.

Yet it seems both unlikely and undesirable to completely eliminate driving. So we will also have to make the auto-infrastructure we have much safer. Speed is a factor in 29% of crash fatalities. Faster cars are both less likely to avoid a collision and more likely to be more dangerous if a collision occurs. So to some extent we can counteract the harms of larger vehicles by reducing the speed that they can go.

The importance of speed to safety is good news for those of us who might want to intervene in the SUV arms race. The speed people drive isn’t based on the speed limit as much as it is based on the design of the street. Most of what we drive on in American cities are “stroads”: wide, high speed, multi-lane drives that still have frequent conflict points like business driveways and intersections with residential streets. Redesigning these stroads could dramatically reduce speed and increase safety.

Road redesigns to reduce speed are often referred to as traffic calming and there are a variety of relatively small interventions that can have dramatic improvements. Something as simple as narrowing lanes could induce drivers to drive more cautiously. Paired with strategic widening of sidewalks, this strategy can be very effective at calming traffic and improving safety. Widening sidewalks in strategic locations, like on alternating sides of the road to give the appearance of a winding street rather than a long, straight, speedway, can further increase the effectiveness of these improvements.

Intersections play a large role in street safety as well. Stop sign violations are a substantial source of vehicular collisions, so intersections are a prime target for improvements. One alternative is to convert some intersections to roundabouts or traffic circles. Carmel, Indiana implemented this change with some success. Smaller alterations can also have some success. Bump outs that reduce the curve radius at intersections both narrow the road to reduce speeds while also forcing cars to slow down more before turning. Raised crosswalks also slow down vehicles while directly improving pedestrian safety.

Traffic calming alterations also have the benefit of being relatively inexpensive and being more amenable to incremental implementation. Places now famous for their human scale urbanism, like the Netherlands, got that way in part by changing road design standards and just waiting for roads to be updated during regular maintenance.

The escalating size of vehicles on our roads, especially in the U.S. and Canada, is a real danger. It puts everyone in danger, especially those outside of cars. But even those who think they are making themselves safer by driving bigger vehicles are less safe than they would be otherwise. It is in everyone’s best interest to stop this arms race. Yet we can’t do it by attacking large vehicles head on. We cannot shame or convince people to just give up what they perceive is making them safer. Instead, we have to fundamentally change the calculus. We have to change the conditions that make it safer to drive giant vehicles by making the alternatives to driving that much more attractive and by making driving safer overall.