United States Space Doctrine

Where the Only Winning Move May Be Not To Play

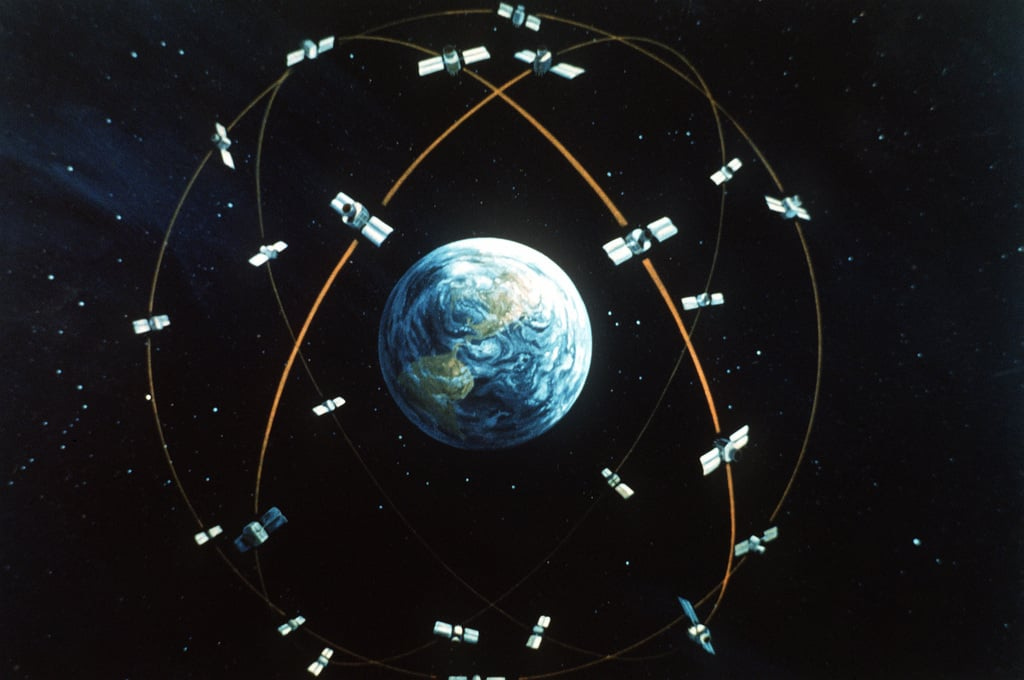

The United States relies on space based assets for a variety of day to day military and commercial functions. The system with which we are likely most familiar is the Global Positioning System, or GPS. Although modern cell phones will usually triangulate your position using nearby cell phone towers (this is much faster) they are capable of connecting to GPS and, in fact, this is how the phones can still navigate even when offline. But beyond personal navigation, GPS is essential to the shipping industry, as locating one’s exact position at sea is otherwise notoriously difficult. Of course this GPS has the same benefits to the U.S. navy and other military personnel.

Satellites also offer essential communication functions. Again the shipping industry must operate away from wireless communication (like cell phone) towers that can transmit information via underground cables. Thus rely heavily on satellite communication. Again, this overlaps with the military’s communication needs. Additionally, the military requires redundant communications systems even when faster and more reliable systems, like cables, are available.

Satellite observations are of obvious strategic use for the military as well. Being able to observe hostile troop movements or keep track of other activities like the construction of military bases and what other assets foreign powers have available is essential intelligence. In other words, the U.S. military makes extensive use of spy satellites. But the commercial sector has found ample uses for these types of satellites as well. Satellite imagery is a notable feature of the now ubiquitous map apps like google maps. But they also play a role in tracking weather events, and scientists use them to gather data on the climate, species migration, and much more.

It can be very easy to take a lot of these systems for granted. Space seems very far away and very disconnected from our lives. But really it isn’t even if people aren’t going to space all the time or settling other planets, satellite systems alone are an essential part of both the American (and global) economy and the American (and most other wealthy nations’) national defense strategy.

Similarly, a lot of people thought that Trump’s establishment of a Space Force was silly. Many people likely had science fiction images of X-wings (or, let's be honest, Tie Fighters) and Gundams flying around above our heads. What could we possibly need a Space Force for when we can barely operate the International Space Station?

But space has become a very real strategic arena due to how essential space assets have become. That doesn’t mean that establishing a Space Force was necessary, or even a good idea, but it does mean that outer space warrants serious strategic consideration on par with something as significant as establishing a Space Force.

Trump’s motivations are unknown, but there were a lot of potential benefits to him. Establishing a new military branch could have scored him political points, so to speak, with his party’s hawks. It could have communicated to the relevant community of policy wonks that Trump, or at least his cabinet, was more competent than they thought. It gave Trump an unprecedented opportunity to fill out an entire branch of the military with Trump loyalists. But what did it do strategically?

First, it signaled a dramatic increase in the priority of outer space as a warfighting domain, probably commensurate with its strategic value. Prior to the Space Force, space assets were managed by the space commands of each branch of the military - Air Force, Army, and Navy. Most prominent was the Air Force Space Command, which played the internationally valuable role of tracking all terrestrial satellites, including orbital debris. This allowed each branch to manage relevant assets commensurate with the strategies of each branch. However, it made the management of mutual assets more difficult to coordinate. It also relegated space to an arena of secondary strategic importance, an environment which was only managed to the extent that it held importance to existing branches rather than having a broad strategic importance in its own right.

But perhaps just as importantly, it signaled an increased militarization of outer space. Even if the creation of the Space Force does not result in an increase in the number of space based assets, it does mean an increase in spending on military uses of space, increasing strategic importance of those assets, and increasing political importance of those assets. Increasing importance also puts those assets at risk.

The increasing importance of space based assets to the day to day operation and tactical functioning of the U.S. military makes them important potential targets for any enemies. Consider just how effective U.S. intelligence has been at tracking Russian troop movements and how key that information has been for the Ukrainian defense. Consider how important satellite communications were for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Any enemy would want to neutralize those capabilities to the best extent they can.

Wealthier nations with more robust space based systems of their own might rely mostly on electronic warfare to neutralize America’s space based assets. Hacking satellites, the computer systems that control them or process the information from them, or interfering with signals from satellites are likely to be the first type of attack. But it isn’t the only option.

In February of 2008, the U.S. government identified that a military satellite, USA 193, had malfunctioned and was going to reenter the atmosphere. But USA 193 also contained enough frozen toxic material that it could present a threat if it re-entered the atmosphere intact. So the U.S. military modified a naval based missile defense interceptor (an anti-missile missile) to destroy the satellite. Most of the debris from this test reentered the atmosphere over the next few months. While some have claimed that the threat of the toxic material given the deteriorating orbit was overblown as an excuse to test and anti-satellite weapon, we can say that at least the debris de-orbited. Other anti-satellite tests haven’t been as careful.

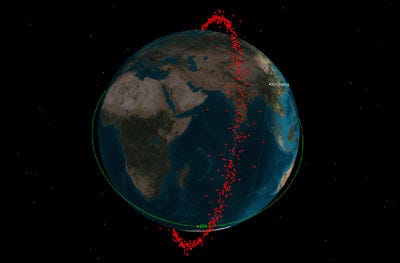

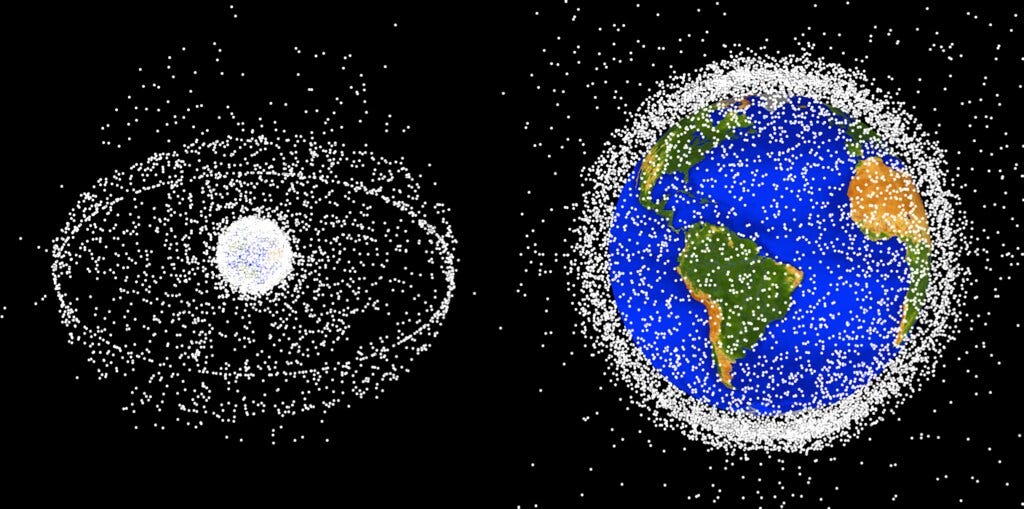

A year earlier, China tested an anti-satellite kinetic weapon (that is, it didn’t explode, it just hit the satellite really really fast), shooting down the defunct weather satellite Fengyun-1C. The impact created over 3000 pieces of debris, which started to spread out a mere 10 minutes after the impact. 10 days after the impact, the debris had spread to cover the entire orbit of the satellite, resulting in a ring of debris around Earth. Three years after the impact the debris had spread even further, essentially interacting all of low Earth orbit. Most of the debris is still in orbit, and may be for decades to come.

The problem with these types of attacks on satellites, is that such debris is not harmless. Each little piece of satellite debris left in orbit after such an attack is traveling at 7 km/sec, or 21 times faster than the speed of sound. Even small pieces of debris, potentially even those less than 1cm in diameter, are enough to cripple any other satellite it impacts.

A year after the American anti-satellite missile impact, an American Iridium commercial communications satellite and a defunct Russian military communications satellite unexpectedly collided. Both satellites were utterly destroyed, and in the process created more than 2000 pieces of debris. Much like with the Chinese anti-satellite test, the debris quickly spread out over the orbits of both satellites. It took nearly 5 years for the smaller pieces of debris to re-enter the atmosphere, but over 1000 pieces greater than 10cm in diameter are still in orbit. The cascade of debris was so bad that the International Space Station had to perform an avoidance maneuver in March of 2011 to avoid collision with some of it.

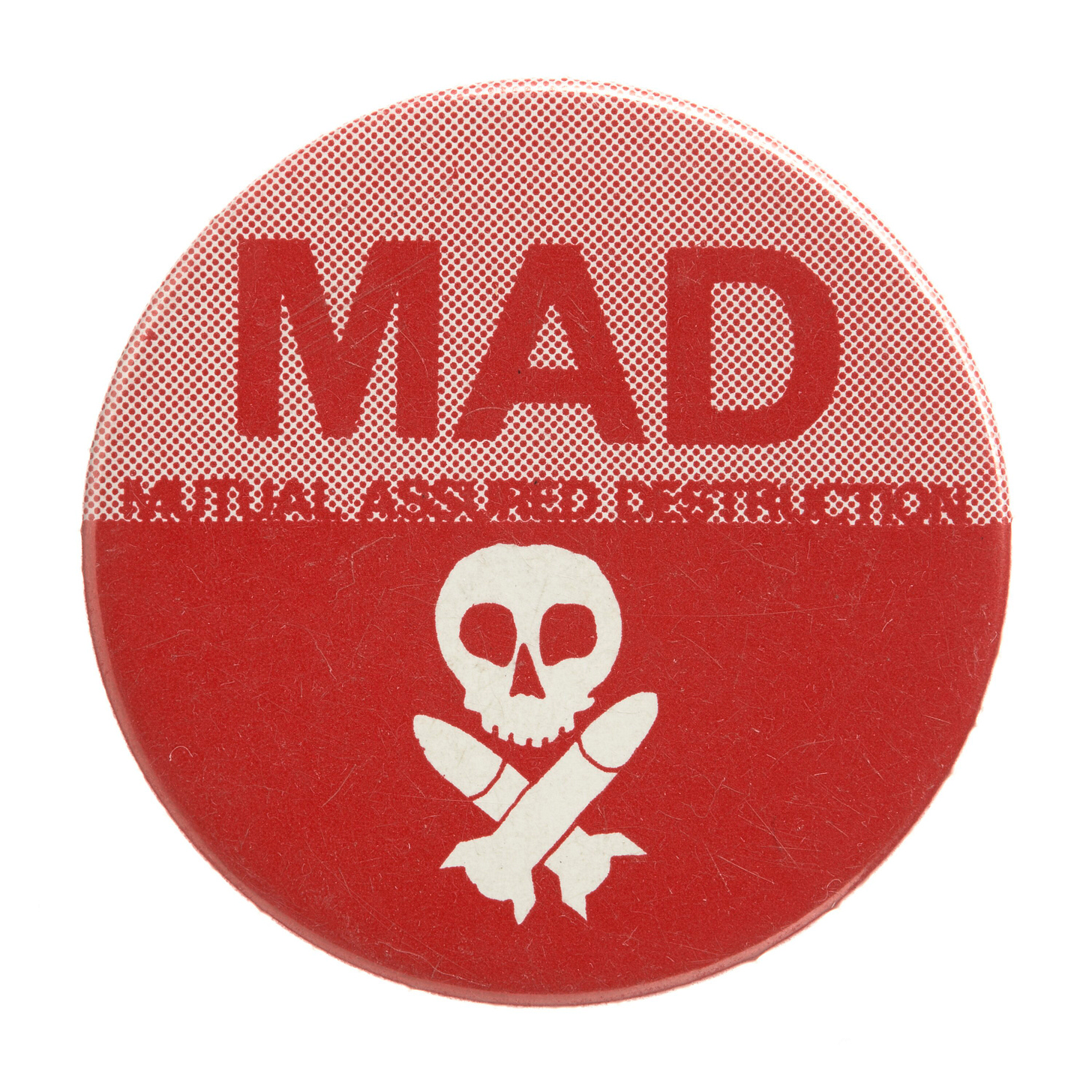

The picture that is starting to come together is a rather horrifying one. The destruction of even a single satellite could create debris that, in turn could destroy other satellites, creating more debris and more destruction and so on and so forth. The potential result is that low Earth orbit becomes so clogged with debris that it is impossible to use it any longer. In other words: the destruction of space based assets could result in the complete annihilation of all space based assets and the denial of space as a site for future assets for the foreseeable future. This wouldn’t just be a setback militarily, it would cripple global commerce as well. A kind of mutually assured destruction.

At least, it's mutually assured for other nations with significant space based assets. Despite the havoc American intelligence has wreaked on Russia in their invasion of Ukraine, they also stand to lose significant assets if they attack an American satellite. Similarly with China, whose space stations have already been put at far more risk than the ISS due to orbital debris.

But what about nation’s without those sorts of assets? In a non-binary situation, where one nation benefits from space based assets and the other doesn’t, then there is nothing deterring an initial attack that might lead to such a cascade of destruction. North Korea, for example, would have little to lose by eliminating the U.S. space based assets. And while North Korea does not as of yet appear to have anti-satellite weapons, their ballistic missile capabilities are sufficient to make them.

Moreover, in the event of substantial escalation of tensions with nations such as Russia or China, United States military success may actually make space based assets more vulnerable. Both Russia and China have invested significant amounts of resources in creating diverse and redundant electronic warfare systems, including communication and intelligence. This means that, while both nations have significant space based assets, they are prepared to operate militarily without them. If the United States is dominating the electronic warfare front and already neutralized space based assets, using kinetic weapons to destroy satellites may be strategically more appealing. In this respect, the mutually assured destruction of attacking space based assets means that the losing side in a war may feel that even the economic fallout of an attack on space based assets might be worth it. Everybody loses in an arms race.

These critiques might look familiar to anyone familiar with nuclear deterrence. In fact, war in space looks a lot like war with nuclear weapons. My use of the term “mutually assured destruction” was not accidental. The term also refers to a nuclear defense doctrine, with the apt acronym of MAD. The theory is that, if any nuclear nation can ensure nuclear retaliation against a nuclear first strike, then the result of any nuclear conflict will result in total annihilation, including for the initiating nation. The theory goes that by making the first strike inherently self destructive, that will deter ANY nuclear strike.

While some have credited MAD for ensuring that the Cold War never turned hot, there are also no shortage of critiques. You’ve already heard two: that power imbalances may diminish the capacity for deterrence, and that deterrence also does not work on parties with nothing to lose from destruction. Deterrence relies on a credible threat. On the one hand, the cascading effect of space debris entombing the planet in a cloud of space scrap is a phenomenon of physics and therefore doesn’t even require the act of a second strike the way nuclear weapons do. On the other hand, the consequences are not equally distributed to the extent nuclear fallout would be. That there would still be winners and losers, rather than all losers, leaves open the possibility of attacking space assets as they become more militarized.

Another critique of MAD is that, while it successfully deters direct conflict between nuclear nations, it may worsen proxy conflicts, as direct intervention risks nuclear annihilation, thus removing intervention as a deterrent. The British sitcom “Yes, Prime Minister” envisioned a scenario where a Soviet invasion of Europe could not prompt nuclear retaliation because even invasion is preferable to nuclear annihilation. Bloody proxy wars were a staple of the Cold War period, and even American involvement in Vietnam and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan could not be directly interceded in or prevented by the opposing power without the risk of more direct conflict resulting in nuclear war. Similarly, the threat of the destruction of space assets might deter intervention and allow conflicts to proceed where they otherwise might not.

MAD also assumes that nuclear weapons work when we want them to, but never work when we don’t want them too. In other words, it precludes the possibility of accidents. And accidents were numerous. On January 23, 1961 a B-52 Air Force bomber broke apart in midair over Goldsboro, North Carolina. It was carrying as its payload two Mark 39 hydrogen bombs. One of them fell harmlessly without arming. The other automatically deployed its parachute and engaged three of its four trigger mechanisms. Had the last switch armed, an area the size of the beltway in Washington D.C. would have been destroyed. In fact, more than 32 similar incidents, so called “broken arrow” incidents, have occurred since the 1950s. These are incidents in which nuclear weapons were accidentally dropped, crashed, or lost. It can be argued that we were closer to being destroyed by our own nuclear arsenal than that of the Soviets.

Tests of anti-satellite kinetic weapons, like China’s 2007 test, are intended to demonstrate a nation’s capability to threaten space based assets. In line with the theory of MAD, it should prevent the escalation of conflict. But in reality, it is only another threat. Without proper care, even a test could start a cascade of destruction in Earth orbit, as China’s test very nearly did.

What I’ve presented so far are, I hope, somewhat far fetched scenarios. But the militarization of outer space and the increasing military importance of space based assets only increases the likelihood of an out of control orbital debris scenario. So how do we make them less likely?

My preference would have been to not have a Space Force at all. Moreover, the United States would benefit from pursuing an information and reconnaissance strategy that is not so obviously and increasingly reliant on space based assets. A strategy of overlapping capabilities, in which every capability supported by space based assets is also supported by several alternative systems, could make targeting space based assets less tempting. For example, supporting communications through satellites is an exceptionally powerful tool, but having backup systems for that communication, like wired communications, airborne radio relays, and tropospheric scatter dishes, would mean that targeting satellites would not disrupt communication and therefore would also be less strategically important.

Relatedly, it would have been better for the United States to create a military branch that reflected a commitment to such a strategy of overlapping systems. For example, rather than a Space Force, an Electronic Warfare Force (OK I admit, I’m not the best at naming things) would better reflect such a commitment. Again, this would embed space as an important, but still incomplete part of military strategy, instead of a potential linchpin of command and control that it is now.

But alas, we have a Space Force. So going forward perhaps the best thing to do is to continue to be generous with our space based assets. The more widespread its usage, the more parties our assets are important to, the less incentive those parties then might have to destroy them. GPS would, perhaps, be the greatest loss of any assets to the world as a whole. This is because its use in global shipping and transportation is so central. Even a Russia or a China on their last leg in a conflict might be reluctant to endanger GPS systems because of how essential they are to the economy of nearly every nation on Earth. We got to this position by opening up GPS to the world. In 1983, in one of the two times a day that the broken clock of Ronald Reagan did the right thing, President Reagan declared that once GPS was completed it would be made open for civilian use. In 1996 President Bill Clinton declared GPS a dual use system, making civilian use an equal priority, legally. Essentially, the United States shared GPS with the world. Devising similar strategies for other space based assets could go a long way in de-militarizing them and therefore defending them.

This drives home the main problem with the militarization of space when thinking about protecting space based assets. Any attack on any space based asset is potentially an attack on ALL space based assets. And such an attack could cascade until the whole planet is entombed in an all encompassing shroud of debris, cutting us off from outer space for decades to come at least. Thus, ironically, the best way to defend these space based assets is to demilitarize outer space. The less temping of a target they are, and the wider their benefits are shared, the less likely they are to be targeted in the first place.