We’ve Got Japanese Urbanism Wrong

National level control is as much a bane as it is a boon

It is a bit of a trope within urbanist communities to ask whether someone was “radicalized” by Amsterdam or Tokyo. Of course people find their way to urbanism in a variety of ways, but these two cities are sort of canonical representations of cycling urbanism and transit urbanism respectively. Though it may be cliche, for me, it’s kind of true. The first time I went to Tokyo, I fell in love with it. I’ve been trying ever since to figure out why I love Tokyo so much more than any other city I’ve ever been to. And my discovery of urbanism in graduate school, and subsequent research into it, has helped me to understand.

I’ve written on this in more detail before, but the summary argument is that the Japanese have just made better decisions about how to build their cities. Their zoning laws are more flexible. They don’t prioritize cars. And the result is a cityscape that is far more amenable to close communities than what we in North America might be used to.

Japan has also been an inspiration to many urbanists for how to solve the NIMBY problem. You see, in Japan zoning laws are determined at the national level. In the US and Canada, zoning laws are determined at the municipal or state/province level at the highest. Many urbanists have suggested that this national level zoning is the key to Japan’s success. It is much harder for a very vocal minority to say no to dense infill development when they have to convince politicians at the national level rather than just their local city council members. But is there more to the story? What is unique about Japanese urbanism that makes it great beyond just affordable housing? And does it really demonstrate the utility of centralized control?

Tokyo is the biggest city in the world. What makes it my favorite city in the world is that it is simultaneously exactly what you would expect the biggest city in the world to be, and also remarkably calm and intimate. In Tokyo you can go to places like Shibuya and see a cityscape of neon lights that makes Times Square seem quaint. But, within walking distance, you can also find quiet alleyways and side streets. You can find the billboards and towers of Akihabara alongside the area’s back-street electronics vendors. You can be awash in the hustle and bustle of city life and the constant noise and activity that comes with it. Or, perhaps merely a five minute walk away, it could be so quiet and still that you could pick out the odd squeaky wheel of a single salaryman biking to work on their mamachari while you enjoy a small alleyway garden before sitting down for breakfast at a bakery with only two tables.

This kind of city is what architect Jorge Almazan calls “emergent” in his book, “Emergent Tokyo.” In it, he discusses how Japanese urban form comes from the bottom up, from citizens responding to zoning laws in varied and interesting ways. And it is this very bottom-up and incremental style of development that makes Tokyo so great.

One such urban form is the Yokocho, narrow alleyways packed with small bars and restaurants. If you’ve ever even planned a trip to Tokyo, you’ve certainly come across the most famous Yokocho in the city: Golden Gai. But the city is awash with them. The legality of live-work arrangements in all zones makes it extremely cheap and easy for a family to convert the bottom floor of their house into a business. But zoning laws tend to prevent the addition of new floors. So instead of taller and taller buildings to accommodate bottom floor businesses, business owners have had to adapt in new ways. The freedom owners have to retrofit or otherwise renovate their properties has led them to transform their businesses into much more open and public or street oriented spaces. In the older commercial areas, these shops slowly encroached on the streets until they became no more than alleyways where no car could ever go. This gives the kind of welcoming and intimate atmosphere that make Yokocho so attractive to tourists and locals alike. The low costs of entry also lends itself to huge varieties of shops, bars, and restaurants. Most of them are owned by individuals, providing a huge diversity in both aesthetics and types of shops.

Another point Almazan makes is countering the criticism of Tokyo for its lack of public green spaces. What Almazan points out is that, while public parks and other formal green spaces are scarce, the city is awash in what he calls “informal greenery.” The compact building and close environment limits individuals privacy. But it also helps to create stronger community bonds between neighbors. These combine to proliferate the solution of greenery. Potted plants and small gardens both provide a sense of privacy without violating the bonds of community in a way a privacy fence or wall might. And so plant life still flourishes in Tokyo neighborhoods, though they lack the kinds of parks and similar green spaces we might be used to in North America.

Of course, what could be more iconic than the glitzy neon lights of Tokyo’s tech district, Akihabara “electric town”? Akihabara isn’t the only place that gives Tokyo one of its signature aesthetics of the contemporary cyberpunk future-city. Called Zakkyo buildings, Almazan describes how these parts of Tokyo developed up in much the same way Yokocho developed out, eating up street space and turning into intimate alleyways. Where land was more valuable near train stations, plots were small and narrow, but building heights were less limited. So buildings were able to add floors in order to accommodate more tenants. Each building supports a huge variety of spaces within, sometimes with a different use on each floor. These could be restaurants, shops, office spaces, and sometimes even residences. These buildings, which rely on the activity on the streets below, present stairways and elevators at the ground level, while enticing walkers with the plethora of neon signs for each of the various tenants. They draw people up and in while looking unique and exciting from the street below.

This bottom up, spontaneous, or as Almazan puts it, “emergent” development is what makes Japanese cities, Tokyo especially, unique and identifiable. Tokyo has a real sense of place and a distinct character as a city. It is also what makes Japanese urbanism great. I want to acknowledge that I understand there are flaws. Not only are the copious jumble of above ground power lines ugly to many eyes (not to mine but I admit when I’m outnumbered), but they dramatically decrease the resilience of Japanese power distribution networks. Underground wires, like in much of Europe, would be better in many ways but would have required curtailing some of the emergent properties of Tokyo. I’m also very well aware that Tokyo, and most Japanese cities in general, are not great places for mobility impaired people. Fortunately, accessibility policies, much like sunlighting policies, are not hindrances to emergent urbanism, but rather the kinds of constraints that are important to the individual creativity that makes it work. And emergent development is why Tokyo feels simultaneously large and human scale, restless and intimate, bustling and peaceful. But this kind of Tokyo, the Tokyo of secret alleyways and mom-and-pop shops, is also in danger.

The very centralization that prevented NIMBYs from stopping the zoning rules that have done Japan so much good are now threatening to change the very soul of Tokyo.

When he died in 1993, Taikichiro Mori was the richest man in the world. He made that wealth building one of the most influential development companies on the planet, and certainly in Japan: the Mori Building Company. Mori was also a fan of Le Corbusier. The company is still in the family, and their buildings are still Le Crobusier inspired. Perhaps the most notable such development is Roppongi Hills. In one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Tokyo, Roppongi Hills boasts anchor tenants like Goldman Sachs and the TV Asahi headquarters. It is also widely disliked by the surrounding residents, who especially resent the noise of the on site concert venue.

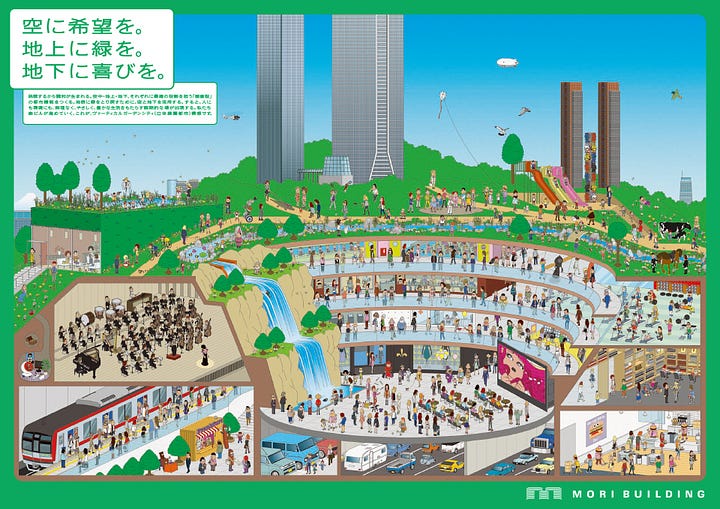

Roppongi Hills looks much like nearly all of the Mori Building Company’s developments. The development is dominated by a single very tall building, surrounded by mostly green space and low rise buildings, with a variety of venues underground. It reflects what the company calls an “urban garden city.” Work and live in the massive tower at the center of the development, enjoy the green space on the ground, shop and play in the underground shopping arcade. Mori is not shy about their dream of turning Tokyo into such a city and, as long as they can afford it, they have no obstacles to just building it.

And Japanese bureaucrats, the ones, you will recall, who have all of the control because all the rules are at the national level, are equally happy to incentivize the Mori dream. I’ve talked before about Japan’s sunlight laws. Well a small-scale owner can’t violate those laws, but a developer like Mori can. If they build the sorts of green spaces they champion in their “garden cities”, called “privately owned public spaces,” they get an increased floor area ratio. That is, they can build a taller building. It should be no surprise that massively wealthy and economically important developers have an easier time influencing national level regulations than regular citizens.

And so it is in Tokyo, not Paris, that developers are implementing something resembling Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin.

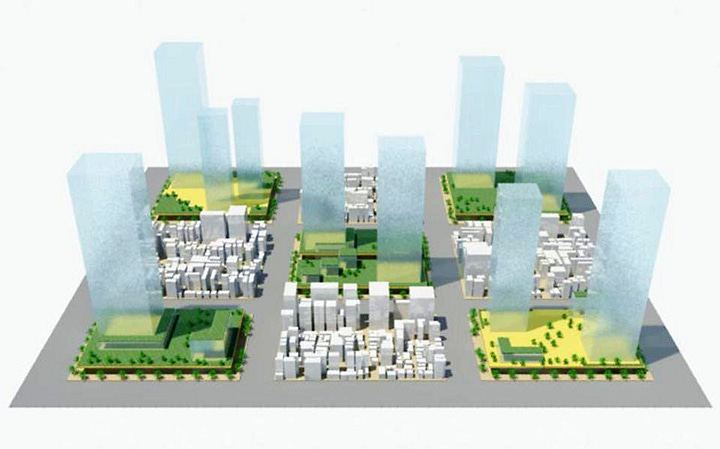

Like with Roppongi hills, developers are buying up smaller plots of land, land developed in the unique and wonderful style we’ve come to associate with Tokyo, and then building these massive “urban garden city” developments in their stead. Almazan presents a map in his book of just such developments as they ramped up beginning in the year 2000. Another data set, from the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat’s Skyscraper Center shows the same trend. Ten new skyscraper developments were completed last year in 2023, and dozens more are slated for completion in the next ten years.

These changes are not bad simply because they are a change. Nor is it bad that such developments exist in general. The Sunshine 60 building, finished in 1978, is an early example of such a development. If nothing else, it is interesting and fun to visit what is essentially a city inside a single building, and the aquarium is fun!

But this is not merely a few new developments. It is a trend. Each new development replaces the kind of emergent development that is so wonderful. The garden city is a city incompatible with the emergent city which it seeks to replace. While the loss of Tokyo’s emergent urbanism is bad on its own, there are problems aplenty with the garden city.

First, we should consider just how public the “privately owned public spaces” actually are. According to Almazan, most of these are very impermeable. They are typically either raised from the street level or otherwise behind a barrier. So while they are technically accessible to anyone, they are intentionally removed from the activity of the street. You can watch documentaries from the 70s that show how long we’ve known that this prevents people from using a space. Many of these spaces also prohibit the most basic of urban activities, such as eating and drinking. Who would actually linger in such a space? So while the artist renderings show these spaces filled with people and activity, in reality they tend to be empty and lifeless.

In general, these designs are meant to be rational. But rational isn’t human. They fail to attend to the human scale. And so, in practice, they tend to be absent of people. Henry Hilton, writing for CrissCross News Japan wrote of Roppongi Hills

“the crowds are unlikely to return once they have been exhausted by the charade of inconvenient walkways that appear almost intentionally to confuse all but those with perfect map navigational skills. The whole maze is far from being user friendly…It dehumanizes what previously had been a largely residential fringe of Roppongi by arrogantly flouting its vast size and by insisting on its boring design…Property czars seem free to spread their tentacles at will in order to swell their rental portfolios.”

All in all, these garden cities are worse than the emergent urbanism that they seek to replace. Yet for Japanese developers and bureaucrats, these highly centralized planned vertical cities are more rational. So they build more and more of them. And, because zoning and all the other relevant laws are at the national level, nobody can do anything about them.

Like much that we’ve talked about here on Taming Complexity, the success of Japanese urbanism has not, in fact, stemmed from the centralized control over zoning laws. Instead, it has stemmed from the incrementalism of Japanese development. Small plots of land, developed by small time owners, adding density over time in accordance with flexible zoning laws and regulations. It was the hands-off attitude that permeated post war development that has kept the consequences of national level control at bay for so long. First because the federal government had more important things to worry about with post war reconstruction, then because of the neo-liberal philosophy that accompanied the Japanese boom economy. But all that has changed in the past 20 years. Now the developers and development officials can collude to create the Tokyo they want. The consequences, and the wants and desires of the residents who built the emergent city, be damned.