I do my best not to ruin each morning by perusing the news from home, so these days my main insight into American life is through the health of its servicemembers overseas. You see, I moonlight as a translator of Japanese. My main gig is medical charts for US soldiers stationed in Japan, and their families. I say “moonlight” because I end up doing it mostly at night, after my “real job” of being a Zen Buddhist priest in the mountains of Snow Country, Japan.

The only translation gigs that survived the Disaster of 2023, when OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT tanked the already-dwindling freelance market, are those protected by law. Medical and military documents are relatively safe, for now. I use these as layers of security against AI-powered job loss. The on-base clinic can handle minor things, but serious problems have to be treated off-base at Japanese hospitals, by Japanese physicians, who write Japanese medical charts that need to be read, later, by the military doctors back on base. Laws around access to soldier/patient data mean the work has to be done by human hands and eyes, with old-fashioned dictionary look-ups and web searches into the minutiae of medicine, so it’s one of the few that still pays well enough to be worth it. Most other gigs have devolved into “MTPE”—machine translation post-editing, which is basically fixing the mistakes in AI translations. This is as maddening as it sounds for half the fee or less.

They can be long, lonely, moonlit nights though. Sometimes weepy. Some charts are real emotional rollercoasters: My heart goes out to parents of any child born premature—what a heart-wrenching ordeal. Others charts are all too ordinary. In addition to their chief complaint, a surprising number of soldiers present to hospital with a BMI above 30. I am here reminded me that in today’s fighting force, soldiers not only serve their country by wielding weapons on a battlefield, but also while seated in front of a computer in an office somewhere. To be sure, each chart must be translated with care. Unlike purely academic translations (my bread and butter until the Disaster of ’23), errors in a medical chart can put lives at risk. So in giving these descriptions of my compatriots and their predicaments as much patient attention as I can muster, I open up and try to let the charts serve me as “test results” for the American experience abroad and in the world.

One moonlit night a few months back, a long chart on a single patient (always a sign of serious trouble) came through just as Elon Musk was chainsawing through the US government bureaucracy in the name of efficiency.

The patient was a 23 year-old private, by all measures a physically-fit young man, who, while on vacation in the Japanese Alps, had failed to land a jump while skiing and broken his femur in 2 places. This is called a “segmental fracture,” because it leaves a segment of bone unconnected to the rest of the skeleton. Lining it back up correctly usually requires open surgery, fixation with plates, and extensive rehabilitation. So a segmental fracture of the femur, the biggest load-bearing bone in the body, was no laughing matter. Our private was inpatient for about 6 months, with another 6 of outpatient treatment, racking up a chart in excess of 500 pages, about 200 or so of which were my responsibility. (It’s another conversation, but long hospital stays are common in Japan, as are inpatient stays just for observation and testing. Or they just seem that way to Americans, whose expectations and experiences of marketized hospitalization are quite different than those in a country with nationalized healthcare).

A medical chart is a document with many authors, built over a period of interaction with a facility, whether outpatient clinic or national treatment center, that describes the patient’s clinical course as a progression of treatments and outcomes over time. There’s a lot of repetition with a difference, as drugs are administered at regular times, patients are periodically monitored and evaluated, and new results come in to updates the old. Medical charts are always additive. Nothing is erased. When mistakes are made, they are crossed out; not deleted.

Hopefully this series of updates on the patient’s condition ends in recovery and good health, but each chart always begins with illness or injury. To start, the circumstances leading up to admission to the hospital will be recorded as soon as they can be determined. Sometimes unconscious patients make this difficult. The sergeant with the “facial crush” injury wasn’t able to explain why he fell off the 2nd story of the parking garage even after he regained consciousness and had his jaw and maxillary sinuses reconstructed—it was only midway through that epic chart, about hundreds of pages in, that his superior officers came for a visit and told the doctor they’d been drinking heavily that night. But whatever the circumstances, they are recorded in as much detail as possible the first time. Then an interesting thing happens that the translator must pay close attention to: As the attending physician enters periodic updates on the patient’s overall status, everything that lacks clinical significance fades away, and the account gradually resolves into a streamlined version of events that we might call, “Just the facts, ma’am.”

But in the case of our young private, one seemingly insignificant fact survived this process. Reappearing again and again in its original form throughout the chart was a bit of detail: The private broke his leg when he failed to land a ski jump while on vacation in the Japanese Alps. One would assume this might resolve into a terse “patient sustained fall/tumble,” to be followed by smooth descriptors: “transported by emergency services, presented to hospital with chief complaint of pain and suspected segmental fracture of left femur.” But the attending physician, anesthesiologist, and surgeon all consistently reiterated the fact that this guy broke his leg by failing to land a ski jump while on vacation in the Japanese Alps.

I expected to discover something, some medical finding or clinical factotum, that would explain it. Maybe that segmental fractures from the vertical impact trauma of a failed landing are different than those sustained horizontally, as in a car crash, or…something. Yet my searches proved fruitless, and as the chart progressed, none of the physicians ever made reference to any such distinction as they diligently planned executed the private’s successful surgery and subsequent rehabilitation. Why, then, did they keep bringing it up?

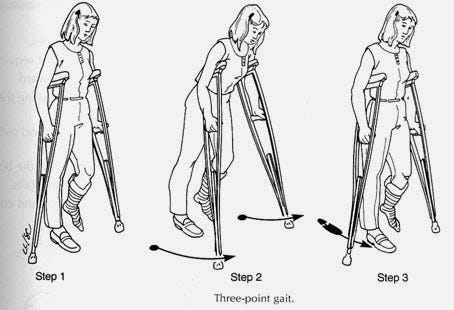

All doubts were dispelled when I got into our private’s rehabilitation records. After doing a few weeks of mobilization on a walker, he told the therapist he’s scared to try crutches. Two weeks later, that he’s scared to try the stairs on crutches. Later, he’s scared to go down to one crutch and try the “three point gait” with the healthy leg. I lose my patient attention and privately, but openly, condemn him, joining the clique of Japanese doctors I’ve assembled in my head: “This fucking guy… If all that’s scary, what business did you have attempting a ski jump? How drunk were you on this vacation?…”

Having a few chuckles to myself while taking a break to recoup my fading energy, I open up a browser tab to catch some headlines and almost have an awakening. The glint off the mirrored shades above that shit-eating grin catches my eye, and I think, “Maybe Elon fucking Musk is right.” My imaginary Japanese doctor-friends were condemning this wasteful expenditure! Months of effort by an entire medical team to heal a soldier who was not injured by an enemy in war, but by his own stupidity while on vacation. Just think of the cost! Sure—it probably wasn’t as high at would be back home in America, where a hospital stay of 6 months could have easily bankrupted his entire family—but it was significant nonetheless, and for what!?

Here, my thoughts turn to my own role in this outrageous boondoggle. Though a pittance by comparison, to have the private’s massive medical chart translated at high speed by a global team of highly skilled linguists isn’t cheap. A three-step process at minimum, with a transcription team, translation team, and editing team, not to mention all the project managers and quality control specialists… All told, a 500-page chart like his could end up costing the US taxpayer $10,000!

Indeed, as my mind flowed over the ramifying events this young man set in motion with his innocent blunder—everything from emergency ambulance services being deployed to a mountainside for helicopter evacuation, to the increased workload on his colleagues at the Air Force base, who periodically visited the hospital to check when he could, you know, get back to fucking work—I could hear the roar and breathe the smoke of Elon’s chainsaw. Here was inefficiency, staring me full in the face, just begging for the teeth of that saw.

Throwing some cold water on the face as I try to settle down and, you know, get back to fucking work, I pondered: What kind of conclusion did I just come to? Is this really the dreaded “inefficiency”? Our young serviceman’s medical debacle certainly seemed like a big waste of resources for a pretty stupid accident, but as I borrowed the MAGA-saw and took some swings at it, the target kept eluding my reach. Inefficient—compared to what? Efficient—to what end? As the reverberation of MAGA-fied rage dissipated, I began to see that my conclusion depended on a lot of assumptions. The first was that all this could have been avoided if he wasn’t stationed overseas as extension of American Empire in the first place. That certainly seemed cheaper and more efficient, but was it? To what end?

*

In Administrative Behavior, published shortly after WWII, Herbert Simon, a Nobel prize-winning economist, founder of AI, and major force in 20th century thought, argued that facts and values are intertwined within endless chains of causation. The values used to evaluate the facts are themselves determined by another set of facts and values, and that set by another set, and so on. Further, these causal chains have to be accounted for in evaluating any facts according to any given values, though our capacity to do so is limited (hence Simon’s famous term, “bounded rationality”). This is a fancy way of saying that everything has a context, and that taking context into account makes for better evaluations. Put differently, failure to do so makes for inadequate evaluations, and unintended consequences.

So the question of whether it is efficient or not for me to be translating our poor private’s medical charts has to be evaluated in the context of the US military presence in Japan. But here the question slides up the chains of causation, and new ones pop out: Why are US soldiers stationed across that island nation? At what cost? And is that “efficient”?

This process could go on ad infinitum (and that is kind of the point) so to cut a long story short, the reason US Armed Forces are in Japan is that they never left after WWII. Okinawa was only given back in 1972. As for the price tag, according to the GAO, from 2016 to 2019, USAF presence costs US taxpayers >$5 billion and Japanese taxpayers >$3 billion annually. Recent changes in the leadership of both countries haven’t altered these numbers too significantly. So, is this expenditure (fact) efficient (value)?

It’s a complicated calculation for at least two reasons. First, we have to ask, “efficient to what end?” And in formulating those ends, hard-to-quantify values, such as stability, security, and even the sanctity of life itself, come into play, making “disagreement” the name of the game. For instance, favoring “security” over other possible values in the formulation of ends might lead one to the somewhat counterintuitive conclusion that it is the very continued presence of the US military in Japan that enabled the country to perform the modern miracle of avoiding active conflicts with other nations for the last 80 years. Of course, the “Speak softly, and stay allied with a Big Stick” hypothesis can never be tested, so there is no way to know whether Japan, if left to its own devices, would have gone back to war. But it’s certainly possible—and if that is the case, then the value of the lives saved by avoiding war for nearly a century surely exceeds by far the cost of a few billion dollars per annum.

Others, valuing “stability,” might argue that maintaining a massive troop presence on China’s doorstep is well worth the price as a deterrent to the territorial ambitions of that would-be hegemon, especially as regards Taiwan. Still others have found no shortage of ways to make persuasive arguments that, while supporting a mid-sized city’s worth of troops and facilities in Japan is certainly not cheap, in light of the cost of the alternatives (e.g. destabilization resulting from pulling out of the region entirely) it is a good investment. Indeed, by any of these routes, one can come to the conclusion that the presence of US Armed Forces in Japan is, in fact, efficient.

And if this is the case, then providing high-quality medical care (and medical translation) to overseas servicemembers is only what we should expect from the world’s most powerful (and expensive) military. Further, on cost alone, US taxpayers should be happy to have their soldiers treated in Japan’s nationalized healthcare system, which, with its collective bargaining for drugs, modest physician salaries, and plentiful small- to mid-sized medical facilities (same-day walk-ins are common even at specialists), is almost certainly more efficient than the bloated nightmare most Americans contend with. The grand total of the cost to taxpayers incurred by our poor private—including the translation fees—is surely fraction of what would have to be spent on him back home in the USA.

At this point in the night, the fumes from the MAGA chainsaw had cleared, and sobering up, my trusty self-interest kicked back in.

Never mind: Fuck Elon Musk and his hatchet-job cost-cutting endeavor. For a moment, to my shame, I may have reveled in how sweet it would be to let that sweet saw rip through that huge pork pie—tens of thousands of US soldiers stationed across more than a dozen bases throughout the only country to remain peaceful since WWII, all sent home overnight! Yet it wasn’t long before I remembered that such a move would open onto an unprecedented geostrategic situation, the consequences of which are not guaranteed to align with any cost-cutting “efficiency” exercise. Recall President Obama’s fateful decision to shift Afghanistan from “boots on the ground” to a drone-based counter-insurgency operation in the mid 2010s—all the talk of streamlined warfare, fewer civilian casualties, and the plaudits handed around for more efficiency in the US fighting force—and how that house of cards came tumbling down onto horrific scenes of former allies hanging onto the landing gear of military transport jets scrambling to hustle VIPs out of country in an admonishment of defeat, not quite a decade later. Given the law of unintended consequences in operations of such vast complexity, cutting costs for short-term gains can result in outcomes so disastrous the very concept of “efficiency” loses all meaning, as when the world’s most advanced military, after two decades, nearly 2 trillion dollars, and who knows how many efficiency exercises, suffered defeat at the hands of a band of regional warlords called the Taliban.

And besides, kicking US troops out of Japan with a swing of Musk’s magic chainsaw would be cutting my own throat. As much as I hate to see anyone get injured and fall ill, when it’s US soldiers in Japanese hospitals, well, that means food on my family’s plate.

Most everyone agrees efficiency is desirable in any number of contexts. But I would wage that when pressed, few can specify what they really mean, especially when it comes to complex endeavors, such as “national security.” Just consider: Is the military itself an efficient means to national security? It’s funny thing. At the local level, sure: servicemembers are often ruthlessly efficient, operation-oriented types, devoted to their tasks. And yet, as the 2022 US pullout of Afghanistan demonstrated, at the level of the organization itself, a human institution with directives, goals, missions, strategies, and tactics, the military is often one of the most inefficient, bungling organizations on Earth.

Probably everyone agrees there is undesirable inefficiency in government, but as the story of the ski-jumping private suggests, it can be hard to specify what exactly that is. And calculating that supposed in/efficiency is no easier. Take the simple case of competing vendors for the same item; say, translation of servicemember’s medical charts. Cut costs by choosing the lower price, right? Fine. Suppose you decide to cut my throat and hire a different translation team that offers a cheaper rate (because they’re using AI?)—I am telling you right now that any the savings obtained by purchasing at a lower price would have to be offset by parallel considerations of the potential losses in product quality and the subsequent ramifications, yet I know you will probably not perform such calculations because they are so costly and time-consuming. That is, you may fire me, but you may also live to regret your efficiency exercise when your servicemembers start coming back with double-amputations instead of the scheduled single limb removal and a host of costly problems arising from medical translation errors.

It may just be late, but I have a feeling similar scenarios are playing out across the American government at this very moment.

The most pressing problems of government overreach and excessive expenditure are rarely so straightforward. Yet discussing them with the chainsaw of “efficiency” impairs our ability to think clearly. Efficiency carries a quantitative gloss not found in “security,” “stability,” and other values values that occur with some frequency in political discussion. Efficiency seems calculable by comparison. But this is an illusion brought on by its avid use by business executives in the parallel, but very different domain of the market. There, efficiency simply means “greater profits,” and its calculation is made possible by a system of money and prices that simplifies the entire world down to red and black ink. In government, by contrast, calculations of efficiency inevitably lead back to those less-quantifiable values, about which political judgements have to be made. No matter who makes them, these decisions are always made on the margin: How much security, at what cost? How much stability can be sacrificed in the name of efficiency in the Pacific? How many lives put at stake by a pullout?

Fans of DOGE, both corporate executives and government officials alike, seem to imagine there are obvious, objective answers to these kinds of questions. That they could be calculated by a sufficiently resourced mastermind. I have my doubts about the possibility of such mastery, but am certain about its undesirability for democracy.