Let’s dive more into the question of commercialization of government functions. I’ve argued that we are wrong to say that commercialization is somehow inherently more efficient than governments. To do this, I’ve shown that bloated government programs are the victim of inflexibility and centralization through the example of the Space Shuttle. In theory, there is no reason a government program couldn’t be flexible and decentralized instead. I’ve also shown that the success of commercial programs like NASA’s come from pluralist competition and an incremental approach to development. It isn’t the magic of the market.

But wait. This is still the story of the government program being bloated and slow while the commercial program is nimble and efficient. I may have identified the underlying mechanisms causing this trend, but the trend still remains. Aren’t I just explaining why commercial programs are better than government ones rather than providing an alternative explanation, as I claim?

In fact, no. The story isn’t quite complete. We have yet to analyze the forgotten history of NASA’s last failed attempt at commercialization.

The Reusable Launch Vehicle Program

Pluralism and incrementalism are key to the success of large scale technological development programs like those at NASA. When commercial programs lack these factors, so-called market efficiencies don’t prevent them from being just as prone to failure and cost overruns as government programs.

In 1994 NASA initiated the Reusable Launch Vehicle (RLV) Program. The idea was basically the same as the commercial crew and cargo program (C3PO). NASA partnered with private industry to develop reusable launch vehicles that were expected to dramatically reduce the cost of spaceflight. NASA hoped that reusability and “finding new ways of doing business,” through industry partnerships and cost sharing would result in an inexpensive launch vehicle. Much like C3PO, the RLV program was designed to reduce costs and improve efficiency through commercial innovation. Rather than traditional cost-plus contracts, the RLV program implemented cost sharing. Industry partners would have to foot some of the development bill. Also, like the Space Act Agreements (SAAs) of C3PO, industry partners would own the launch vehicle at the end of development. NASA would then purchase the use of these vehicles as a service.

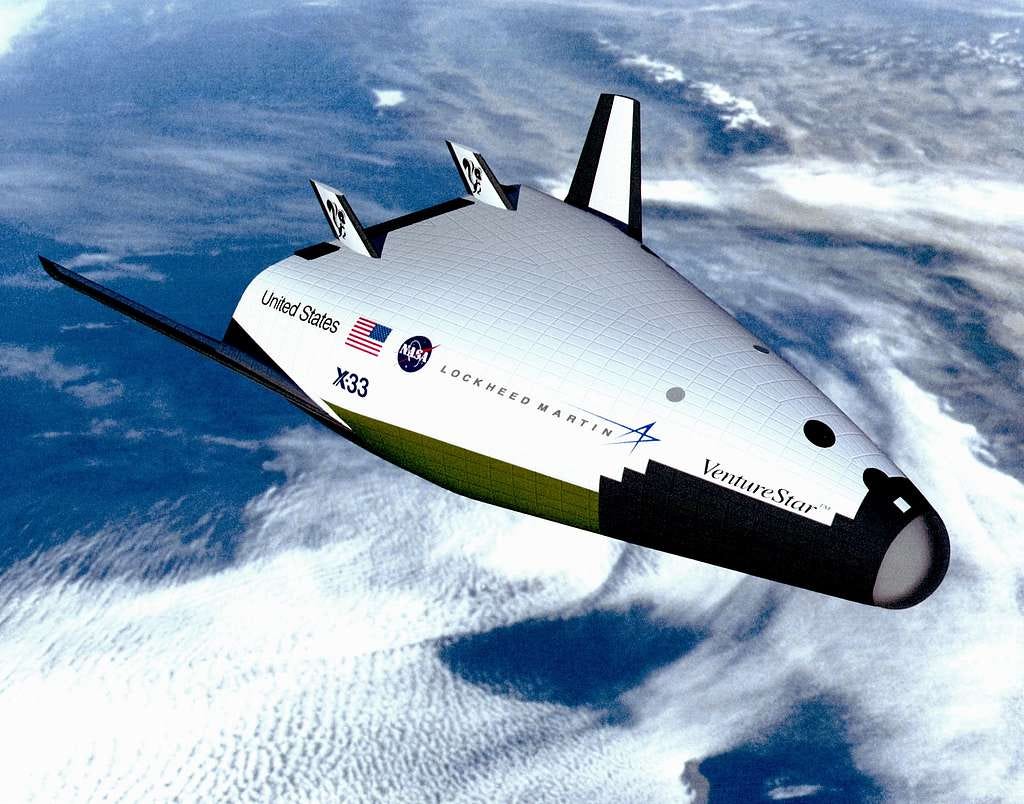

By 1996 NASA had contracted two vehicles for the RLV program: the X-33, with Lockheed Martin as the partner, and the X-34, with Orbital Science (a name you might be familiar with due to their participation in the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services Program). While the program to develop these two launch vehicles had the same commercialization strategies of C3PO, they lacked the incrementalism. The program lacked annual performance targets or a plan of action for schedule delays or cost overruns. The initial cost estimate simply assumed that needed technologies would be completed on schedule. They were not subdivided into many phases like C3PO was. There were no performance targets upon which continued funding depended, and no alternatives if either of the launch vehicles failed. And fail they did.

In 2001 the X-33 was canceled after a failure of the composite fuel tank during testing. The project was five years into development and only 40% completed. The total cost had ballooned to $1.5 billion, of which NASA had contributed $922M. That same year saw X-34 canceled as well. After NASA spent $102M on the project over the five years of development it had only achieved an unpowered prototype, flying only if towed by an airplane.

Both projects were over budget and behind schedule, with no real prospects for leading to commercial launch vehicles even if NASA had continued the program. NASA and their industry partners implemented the RLV program by blindly plunging ahead, with a predictable outcome.

Because of the inflexible approach, test flights were expected to be delayed by an additional five years and costs were estimated to increase by another 45% for the X-33 and 307% for the X-34. NASA did not know whether even those additional funds would be sufficient to complete the program. In fact, it was precisely because of budget concerns that both programs were canceled. The one thing commercialization was supposed to help with the most. Commercial cost sharing and plans for industry partners to own the vehicles after development were not sufficient to save the RLV program. It takes more than just commercialization to avoid inflexibility.