Why Does the Government Spend So Much?

The Iron Triangle and the Consequences of Emergent Phenomena

Have you ever wondered why, no matter the fiscal crisis going on in the United States, congress never seems to be willing to cut defense spending? Why, when other programs are being cut, defense spending always seems to be increasing? In 2022 about 47% of the United States’ discretionary spending was on defense. We’ve all heard of the military industrial complex before, and we likely all wonder why it seems to have such a dominant place in American politics.

It might be tempting to look at it like some sort of conspiracy. Or perhaps the result of warmongering elected officials. Who can we vote out to get our spending better balanced with our own values? Unfortunately, it isn’t quite that simple. Rather than result of individual decision-making, the primacy of the military industrial complex is what we call an emergent phenomenon.

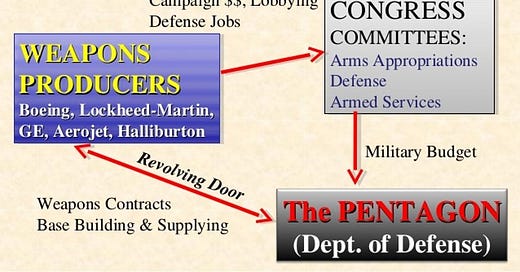

In 1981, Gordon Adams, a professor of Foreign Policy, published a book called “The Iron Triangle,” thus coining the term. What he describes is a web of common interests between three different actors. Congress and their relevant committees determine the military’s budget. The Department of Defense (DoD) has a revolving door with their contractors. DoD officials often end up working for defense contractors when they retire. The DoD gives out weapons contracts, base building contracts, supply contracts, etc. Those defense contractors in turn donate money to the campaigns of congressional representatives, they directly lobby, but even more importantly they provide defense jobs in the districts of those representatives.

The F-35 program is a good example of how this process works. Initial estimates in 2001 showed that each plane would cost $70M, with a total acquisition cost of about $230B. By 2012 the cost per plane had inflated to $140M and the total acquisition cost to $400B. Even four years later in 2016 the Pentagon wasn’t even sure if the F-35 was going to be fit for combat. Still, the first test flight of a fully enabled F-35 didn’t happen until January of 2023, and full rollout slipped to December of the same year at the earliest. Is over 20 years too long of a development time for a program that has doubled in cost? How did such a program continue to get more and more funding despite its obvious failures and setbacks?

The answer is the iron triangle. Elected officials get reelected in part by bringing jobs to their districts. And military contractors get projects funded by having the support of their elected officials. Only three states haven’t gotten some jobs from the F-35 program, and 33 states have more than 100 people employed for work contributing to the program in some capacity. The prime contract went to Lockheed Martin, but suppliers, vendors, and sub-contracts included several companies from Rolls-Royce to General Electric. The F-35 program brought a lot of jobs to a lot of districts. So it makes sense that it would continue to get funding when the political costs of cutting it, or even shrinking it, are unbearably high for many representatives.

What is important to remember is that the iron triangle and its consequences are not inherent properties to systems. They are, instead, emergent properties. It can be hard to distinguish between the two. After all, if overblown federal programs aren’t the result of some master plan by corporations to leech public money, then it must be an inherent problem to government programs. Right?

Just because an outcome is an emergent property of a system doesn’t mean it is inherent to that system. Just as different cities have varying degrees of success in dealing with crime or homelessness, different government (and non-governmental) programs have varying degrees of problems with the iron triangle. I’m sure few of us have heard about Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) pork. In fact, one of the main jobs of the BIA is to streamline the relationship between tribal governments and the federal government by revising and reducing regulations and paperwork.

Instead, emergent phenomena like the iron triangle are the result of how different systems interact with each other and short-term, narrow thinking of the actors involved. This makes the iron triangle and its ilk very resilient. You can’t eliminate it with only reforms to the government. Private contractors are just as culpable. Instead, if we want to fix the problem we have to re-frame it. We cannot see it as just a problem of pork barrel spending. We must see it as a problem of relationships. One way to break it is to include more relationships. Representatives on defense related committees are usually included *because* of their relationship with defense spending. Congressional committees could include some members of congress who have opposing incentives as well. Alternatively, programs as large as the F-35 could have performance target requirements. This might make contractors wary of committing the capital necessary to influence so many Congressional districts at once. Tackling the conditions under which those relationships form the way they do, that is breaking the triangle itself, is the only way to prevent the problems the iron triangle causes.

Theres a logical fallacy (there's probably a name for it) where explanation is misconstrued for approval/complacency, which I hate for sure. Like providing more nuaced reasons Putin's actions result in being attacked as a Russian sympathizer.

However, I get the impulse because such explanations are often followed by weak-sauce proposals. Performance targets? More diverse senators in committee? Really?

In my eyes, showing the behavior as a robust, stable phenomenon from a confluence of different interest suggests more extreme action, like gutting the whole thing.