Why is Government Spaceflight So Expensive?

Inflexibility and Centralization in the Space Shuttle

Government programs are expensive and private enterprise is efficient. Quite a few policies have been passed based on this premise. A history of privatization since Thatcher and Reagan could take a whole book, much less a substack article. Suffice it to say that I am not convinced that just because a project is led by a government it is destined to be more expensive and less efficient. But that conviction bears examination. Especially considering that, in some cases, privatization has seemed to streamline things.

A good example is human spaceflight. The first time SpaceX launched astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) it made the news, but after 11 crewed launches and 42 astronauts sent to space (at time of writing), it’s starting to seem rather routine. And all for a fraction of the cost of the space shuttle. And that doesn’t even account for the performance of the commercial cargo program. In short, the success of spaceflight commercialization, broadly under the purview of the Commercial Crew and Cargo Program Office (C3PO) seems like a case study demonstrating the efficiencies and cost savings of privatization.

But that commercialization seems to have been successful doesn’t automatically mean that a government program has to be more expensive. Why, then, do so many government projects suffer so badly from bloat? Specifically, why have government spaceflight projects fared so poorly in this regard?

Inflexibility and Centralization of the Space Shuttle

After Apollo, NASA developed a follow-on program to replace the expendable Saturn V with a reusable launch vehicle: the space shuttle. But the program was marred by cost overruns, schedule delays, and two tragic disasters. If not because NASA, as a government agency, had ossified into a sluggish and bloated bureaucracy, then why?

Unintuitively, the shuttle suffered from too much agreement. The decisions that characterized the development of the space shuttle were highly centralized. The shuttle program lacked sufficient debate. No authority challenged the shuttle early enough to head off problems.

Disagreement about the space shuttle (1) was limited to the early part of the development process, (2) focused on features rather than fundamentals, and (3) did not include positions that supported shuttle alternatives.

The only early dissent was a report by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and RAND corp in 1970. They supported continued use of expendable launchers rather than an expensive development program for a reusable launcher. The Department of Defense (DoD), and contractors like Lockheed and Aerospace Corporation all supported the space shuttle. The fundamental assumptions they all wanted were reusability, crew capabilities, satisfaction of DoD requirements, and a U.S. launch monopoly. NASA, too, supported these fundamentals despite some designers' safety concerns. Even when early problems arose, like heat tiles falling off during transportation, no one saw fit to question these fundamental assumptions.

The only groups which offered substantial criticism of these fundamentals, satellite companies, satellite manufacturers, and scientists, were ignored. They wanted smaller, cheaper, more predictable launches but the DoD and others didn’t. These detractors didn’t have enough power to challenge the consensus. As a result, they were excluded from influence despite having a legitimate interest in the outcome.

While congress was not a cheerleader for the space shuttle, opposition was tempered by what is referred to as the “Iron Triangle.” We’ve written before about how the Iron Triangle contributes to high defense spending. In the case of the Space Shuttle, Aerospace contractors, NASA bureaucrats, and congressional representatives all mutually benefited by funding the shuttle. Relevant committees were dominated by representatives who already had NASA centers or their contractors operating in their districts and who wanted to maintain those high paying jobs. The same mechanisms later drove opposition to NASA’s commercial program when, in 2010, 16 members of congress who represented districts near NASA centers wrote a letter opposing the new policy. This Iron Triangle further centralized decision making.

The shuttle suffered from too much agreement..no authority challenged the shuttle early enough to head off problems.

Without dissent, no one with political power addressed problems. The space shuttle suffered from substantial inflexibility: it had long development lead times, high capital intensity, large unit size, and high infrastructural dependency. Yet there were no opposed voices to point this inflexibility out before it caused problems.

Despite the shuttle program beginning in 1972, it didn’t fly until 1982 a full decade later. A technology as complex as the space shuttle requires experience to properly understand what could go wrong. And NASA engineers couldn’t even begin to gain that experience until the program was already a decade old, and billions of dollars were already sunk.

By 1984 NASA had already spent $15B in research and development for the shuttle, about $45B in today’s dollars. NASA estimates launch costs at $450M for 53k lbs into orbit. The cost to replace a single shuttle was $6B. With so much money sunk into the initial development and construction of the shuttles, NASA officials had a huge financial incentive to try to recoup these costs through frequent launches and a domestic launch monopoly.

Furthermore, only four shuttles were in the fleet at one time, making each shuttle indispensable. A scrubbed launch meant years of schedule delay. Maintaining launch capacity required as close to perfect operation as possible. Having such a small fleet meant very little leeway for anything to go wrong. Counting on perfection is bound to result in failure, especially in such a technically complex system.

A project as massive as the space shuttle also has substantial dedicated infrastructure. The launch, maintenance, and assembly facilities, manufacturing facilities for unique parts, contractors, and crew training were all dedicated to the shuttle and not applicable even to alternative launch vehicles. Worse, the shuttle was the only vehicle designed to take large DoD payloads. In order to achieve market domination shuttle alternatives for private payloads were deliberately suppressed. The shuttle, therefore, was a necessary technology for access to orbit.

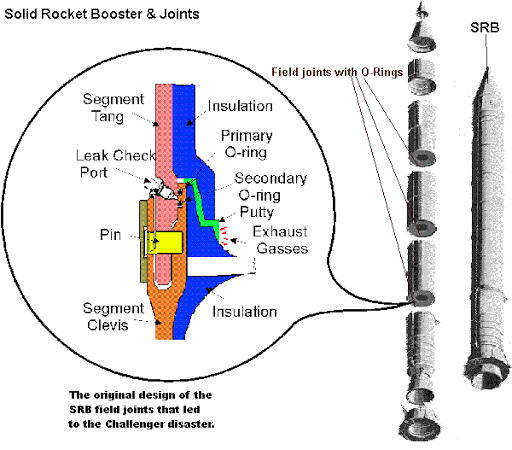

If everything works exactly as intended, inflexibility isn’t a problem. But when is that ever the case? Inflexibility can turn otherwise small errors into devastating setbacks. The disasters in 1986 and 2003 are the most obvious examples, but inflexibility caused a plethora of other problems.

Meeting DoD specifications required the shuttle to be very large. So when launching private payloads, the shuttle would launch several together at once. But with only four shuttles a single missed launch resulted in a perplexing web of problems. They couldn’t just fit them all on the next launch. Each subsequent payload had to be re-evaluated to see whether and when payloads from a scrubbed launch could be squeezed in. A single scrubbed launch could mean disproportionate delays for payloads that were lower priority. Delays were thus more expensive and took longer to recover from.

Unique parts were unnecessarily expensive because NASA had to pay for the upkeep of idle manufacturing facilities just in case they needed more. These costs, along with all the expenses of development, had to be spread over as many launches as possible. A missed launch, or a delayed launch schedule, therefore increased the cost of each subsequent launch! This feature created intense pressure not to delay or cancel a launch, a problem that contributed substantially to the Challenger disaster.

Having a small fleet and long lead times together made learning difficult and slow. Even if NASA officials were clever or astute enough to realize the shuttle’s problems early on, even if they did so after a single launch, it would still have been too late! NASA had already spent billions in unrecoverable costs up front, so canceling the program would not have saved enough resources to pursue a replacement. This, in turn, incentivized NASA (and others like the DoD and even opponents like satellite operators) to plunge ahead with the shuttle, even when its flaws were apparent. As Diane Vaughn noted in her book, “The Challenger Launch Decision”, this normalization of flaws was the primary cause of the Challenger disaster.

The Apollo program was an epic achievement of human engineering. Although it couldn’t have happened if NASA hadn’t essentially had a blank check, the total cost was still only $257B in today's dollars. Less than the aforementioned F-35 program. The program that followed it could have been just as efficient. That the space shuttle was such a lumbering, bureaucratic behemoth wasn’t inevitable. Nor was it an inherent feature of being a government program. The failures and expenses of the space shuttle were brought about by its inflexibility. An inflexibility enabled by centralized decision-making and a lack of pluralism.