You Can’t Go Home Again

How Markets Can Lock Us Into Worse Technology

We don’t often think about how our society picks new technologies. It doesn’t really seem like a choice, more like a natural phenomenon. Technology seems almost to evolve, like some form of life. But it doesn’t. We don’t pick new technologies the way we pick what we have for dinner, but we do pick them nonetheless. We just pick new technologies through complex systems. Consider some of the technological choices we’ve already discussed at Taming Complexity: choosing what material to build airplanes out of, or what kinds of apples to grow.

Perhaps one reason technological choice doesn’t actually seem like a choice, is because most people don’t really get a say most of the time. Did anyone ever ask you if seemingly every new appliance on the market should connect to the internet? Or if the tactile knobs and buttons in cars should be replaced with touch screens? Did you ever get a chance to say no to LLMs like ChatGPT? We’ve discussed, through the example of Elon Musk, how the way most new technologies get funding leaves most people out of that process and gives us worse results (as well as some ideas for making that better). But this isn’t the only mechanism by which technological decision making can go wrong.

Economist and political scientist Charles Lindblom praised market systems for their decentralized coordination. He pointed out even something as simple as a morning cup of coffee is made possible because of the coordination between growers, wholesalers, shipping companies, roasters, distributors, and retailers. This coordination, which would be nearly impossible to achieve through command (a single coordinator) is routine in a market system. But he also pointed out many ways that markets fail. Sadly, this nuance is often lost with most modern market proponents.

Let the market decide is a mantra that many of us are likely familiar with. We can’t raise the minimum wage because that would distort the market. The laws of supply and demand will give us the optimal outcome (optimal for who?)! When critics point out the many less than optimal outcomes of ostensibly market systems today, market proponents often respond with a myriad of reasons why those outcomes are the result of distortions in the market, not the market itself (obviously the market will determine the fairest wage for child labor, but I digress). But sometimes it is markets *themselves* that lends to bad outcomes. This can be the case for technological choice.

Production of consumer goods generally follows the supply and demand curve that we are all so familiar with. Goods in high demand fetch increased prices, while firms must sell goods in low demand for less. Increasing prices will lead to consumers selecting alternatives (assuming some elasticity in demand, but elasticity isn’t the focus of our discussion here) and lower demand, while decreasing prices might entice consumers and increase demand. These kinds of consumer goods generally reach an equilibrium, where supply and demand balance one another and the price of the good is (relatively) stable. Obviously in the real world there are all sorts of confounding factors. Bird flu can destabilize the price of eggs, but that destabilization is still because of the laws of supply and demand. The sudden reduction of chickens constrains the egg supply, thus increasing the price.

The reason these sorts of goods always reach an equilibrium, and don’t have runaway demand or pricing, is because of diseconomies of scale. Let's stick with chickens as an example. If you’re a chicken farmer, you can farm chickens for eggs or for meat. The choice exists between these two goods. You buy egg chickens. If you have a small number of chickens roaming around, it costs a lot of money to keep the chickens, feed them, and gather their eggs. But if you have a lot of chickens, you can take advantage of economies of scale. You can stuff more of them into your farm, automate the egg collection, buy feed in bulk, and generally pay less money to get more eggs.

But at some point, it no longer gets cheaper to have more chickens, it gets more expensive. When your chicken warehouse is full, you have to buy another one. That doubles the amount of land you have to have, and doubling your land is usually more than double the price. As you drive up demand for the feed, the price of the feed goes up as well. Similarly, at some point you’ll need more workers, which means you might need to increase wages to attract enough people. There is some number of chickens at which, when you buy more chickens, the cost to produce an additional egg actually starts to go up, not down. This is a diseconomy of scale.

Meanwhile, producing more eggs drives down their price. So now if you want to buy more chickens to lay more eggs, you have to pay more per egg and sell them for less. So when the next farmer comes along and is trying to decide what to do with their chicken farm, they see high production costs and prices for eggs, so they’re going to, instead, choose meat chickens. And so not only does this process stabilize the price and supply of eggs, but it also prevents all chicken farmers from selecting egg chickens.

But what if those diseconomies of scale never materialize or materialize at impractically large scales? This is the phenomenon that economist W. Brian Arthur identifies in his studies of the process which he calls “lock-in.” When firms introduce two new competing technologies into the market, sometimes they follow the normal rules of consumer goods. Think smart phones, where Android phones control about 70% of the market worldwide, iphones control about 30%. And it's much closer to 50/50 in the US. But sometimes, as the scale of one technology increases it there are no forces pushing towards equilibrium. Instead the benefits to that technology just accumulate in a process called “increasing returns.” This leads to a runaway effect where one single technology dominates the entire market.

Let's take an example of the competition between Blu-Ray and HD DVD. Between 2005 and 2008 Toshiba and Sony battled to see who’s media format would gain dominance. While HD DVD had an initial lead in 2006, by 2007 Blu-ray had won out. It wasn’t because it was the better format. Both media formats were part of a sociotechncial system. They needed hardware manufacturers to make the electronics to play the media, content producers to film TV and movies in their format, retailers and distributors to carry it, and government regulations to provide legal protections like copyright.

People would only buy media in a particular format if the TV shows and movies they want to watch are available, if they can easily buy a player for that media, and if it is carried in stores. Toshiba had no direct involvement in media production, and so had to rely on studios to agree to exclusive deals with them. Sony, on the other hand, already had their own production studio and owned Columbia pictures. In 2004, they increased their library even further by purchasing MGM Studios. In 2006, Sony launched the PS3 gaming console with an included Blu-ray player. Even though they sold the console at a $200 loss per unit, millions of gamers now had a Blu-ray player by default. The PS3’s competitor, the XBox360 from Microsoft, sided with Toshiba’s HD DVD, but you had to buy the player separately. In 2007 Blockbuster, which was still a power player at the time, agreed to rent exclusively Blu-rays. This was enough to swing the momentum in Sony’s favor. The death knell was in 2008, when Blu-ray’s momentum convinced Warner Bros/New Line Cinema to sell their media exclusively on Blu-ray. Sony paying them $400M didn’t hurt either. Later that year, Toshiba admitted defeat and ceased HD DVD production.

You might notice something peculiar about this process. At no point were any of the increasing returns for Blu Ray based on the performance of the technology itself. In other words, the process of increasing returns and lock-in seem to be independent of the quality of the technology. What matters are early advantages, and those are often fairly random, or the result of business acumen and gamesmanship, not which technology is actually best.

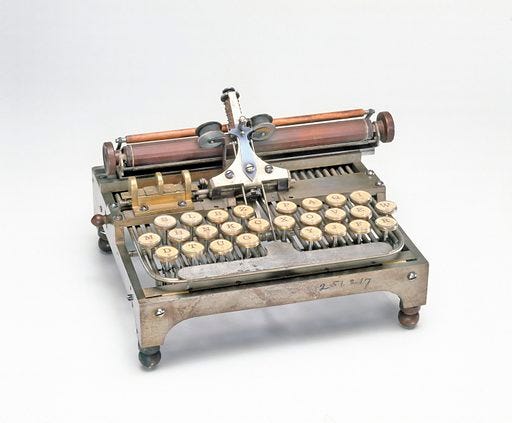

Indeed, when multiple technologies are competing against one another, this process often selects and locks in the inferior technology! One example that Arthur studies is QWERTY keyboard. The QWERTY keyboard has a fairly non intuitive layout. Users must typically gain proficiency through formal training, as experience alone usually leads to a fast version of the hunt-and-peck typing method rather than touch typing. Novice typists can learn an alphabetical keyboard faster, and the Dvorak and Colemak offer more efficient layouts that may improve typing speed (study results are mixed) and reduce finger strain.

The story we most often hear is that QWERTY was the most efficient layout that didn’t jam old mechanical typewriters, but that isn’t actually the case. By the time typewriters were adopted widely enough, and typists generally proficient enough for jamming to become an issue, QWERTY was already the dominant layout. Initially nearly every typewriter company had their own layout. But that meant that hiring a typist who was experienced using one layout didn’t mean they would be experienced on the layout used by the brand your company purchased. So smaller firms just started buying the typewriter brands used by larger firms, since more typists were getting experience at larger firms. Other typewriter brands, now left out in the cold, changed their keyboard layouts to match those of more popular brands, and eventually that process converged on the QWERTY keyboard. Not because of some mechanical efficiency, but because it happened to be purchased by large firms early on.

By the time anyone was paying attention to layout efficiency, it was too late. No one wanted to rehire or re-train all of their typists. Much less replace all of their typewriters. And when computers came around that layout had been locked-in for nearly a hundred years! So it certainly wasn’t going to change then. Even now, as smart phones and tablets still use the QWERTY keyboard. All this despite digital keyboards having completing different typing methods, usually using thumbs or a single finger for the swiping method. A different layout would almost certainly be more efficient!

Other examples abound. The competition between VHS and Betamax in the 1980s resulted in VHS becoming the dominant, and exclusive, video technology despite being technically inferior. The US selected light water reactors over other much safer nuclear reactor designs. Electric cars competed with gas cars from the very beginning of the automobile. Obviously gas cars won out, but we have come to realize now that perhaps that was a very poor choice.

When we choose between multiple new technologies and use market mechanisms to make that choice, we often choose poorly. Those poor choices are not the result of distortions either. Rather, they are the result of those market mechanisms themselves. In situations where gaining a lead yields increasing returns, markets produce a runaway effect rather than an equilibrium. That can in turn lead to one technology dominating at the expense of all the others. And because those early leads are often due to random effects rather than some real, or even perceived, superiority, the worse technology can easily be the winner. It behooves us, then, to be realistic about the strengths and weaknesses of market mechanisms. These cases should also remind us how easy it can be to wind up stuck with a technology we don’t want, or worse, one that actively makes our lives worse. You can’t put the genie back in the bottle, but you don’t have to make a wish. While we can’t undo the development of bad technology, we can try to be more flexible, and give ourselves the opportunity to re-choose when one technological development isn’t working out.