Are the Kids Alright?

Why our focus should be on giving American youth an exit from a smartphone-laden life

“Smartphones have ruined our lives.” That’s at least how a colleague of mine relayed his students’ consensus when he asked them about digital technologies. A classroom of college undergraduates isn’t really a representative sample of America, skewing more white, affluent, left-wing, and (let’s face it) anxious than the average citizen. But it’s a sentiment that we should take seriously.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt last week published The Anxious Generation, a book on a seemingly growing mental health crisis among young people. According to him, the cause of the problem can be found in young people’s pants pockets: their smartphones.

There’s no shortage of supportive, albeit contested evidence. Youth rates of suicide, anxiety, and depression took off only a few years after the introduction of the iPhone. Some argue that increases in mental health disturbances follows lockstep with the expansion of high-speed internet access. Many young people themselves tell researchers they prefer a world where neither they nor their friends use social media.

Like for so many wickedly hard problems that we face, it’s important to avoid simplistic narratives. Increasing depression and anxiety rates might have more to do with normalizing admitting mental health problems. At the same time, might this normalization process, vis-a-vis social media, exaggerate or maybe even worsen people’s struggles? Unfortunately, social problems are not so easily understood. What we need most, then, are ways of partly solving complex and divisive social issues despite the fact that we don’t and probably won’t ever totally comprehend them.

Rage Against the Machine

Haidt is no stranger to eulogizing the apparent decline in the resilience of young people. His previous book with Greg Lukianoff, The Coddling of the American Mind, set its sights on the excesses of prioritizing the emotional safety of US college students over their intellectual development. This is in the first time, however, that Haidt has made technology the focal point of his argument.

That focus is somewhat unfortunate. Having myself spent years with my nose deep in studies exploring the consequences of different technology on our social lives, I’m keenly aware of the tendency to confuse the symptoms of a social problem with its causes.

To be clear, I’m not exactly calling out Haidt here, but rather the online discourse surrounding his book. Haidt is actually quite clear: the impacts of smartphones and social media make sense in relation to the simultaneous loss of play-based, freedom-oriented childhoods. But hearing Internet takes on the Anxious Generation, you’d think Haidt was starting an inane debate over a question no one should be asking, “Smartphones, good or bad?”1

That many of the people looking to score a sick Twitter burns haven’t seemed to have even listened to an interview with Haidt or, much less, read an even-handed review of his book makes their eye-rolling dismissals of his social media criticism ironic, to say the least.

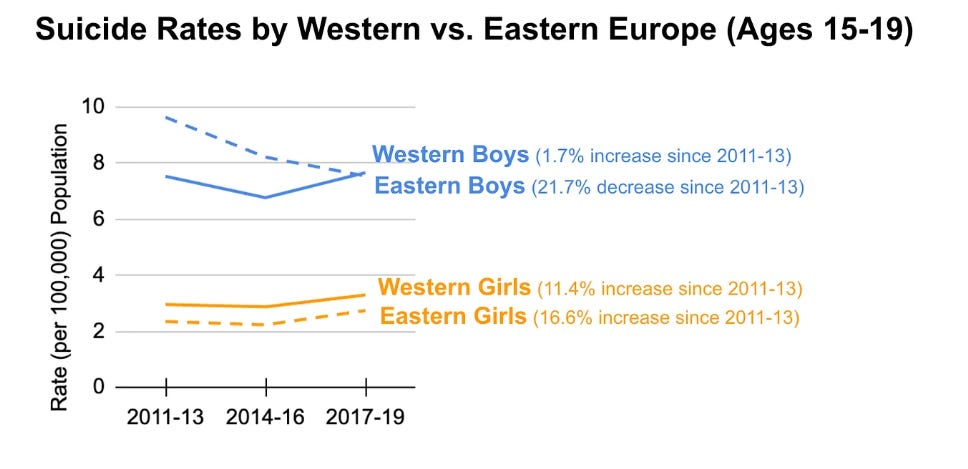

More important, however, is how this strawman version Haidt’s argument prevents a sensible conversation about technological impacts. As parts of broader sociotechnical systems, social media and smartphones’ benefits and harms have as much to do with the human context as their design features. Noticing that youth mental health issues in Europe, especially in its eastern parts, have not increased so dramatically shouldn’t lead us to deny that social media could have deleterious effects but to follow Haidt in thinking about what might make American kids more susceptible.

Does the Technological Tail Wag the Social Dog?

Although Haidt’s book is easily (and unfairly) dismissed as pop psychologizing a moral panic, it isn’t out of line with what people have found in my own field of Science and Technology Studies. Natasha Dow Schull’s Addiction by Design explored how casinos and video gambling machines were explicitly built to put problem gamblers into a flow-like state she called “The Zone.” While we might assume, at first blush, that gambling is about money, what really hooks people is the ability to find a psychological release. The bright lights, sounds, and repetitive button pushing offers a temporary escape from everyday stresses and problems. All that wouldn’t be necessarily a bad thing, except that some people earn their living by enticing people to stay in The Zone as long as possible.

At the same time, the take home lesson isn’t that people are being duped by Big Gambling into betting the farm. Neither is Haidt claiming that young people have been zombified by their phones (at least I’ve never gotten that vibe from him). Schull’s interviewees often got into gambling during moments of personal crisis. As much as their playing quickly led them to unreasonable places, they were acting quite rationally when they started playing slots as a way to unwind from their day. The trouble is that, once they became addicted, exiting the self-destructive cycle was very difficult.

A similar argument about Internet use was articulated by Sherry Turkle back in 2010. Her book, Alone Together, was never about rejecting new technologies or about pining for the good old days. Rather, the point was paying attention to the additional risks posed by novel technological capabilities during our moments of vulnerability. Social media connections can be blessing in hard times, when we are far from loved ones or facing a personal crisis. But the immediacy and ease of contact can be a double-edged sword. Sometime we end up using digital technologies in ways that amplify our anxieties and problems, such as when troubled young women are drawn into pro-anorexia communities or when kids struggling with their self-esteem start measuring their own worth against seemingly “perfect” influencers.

As Haidt also points out, young people center their lives around smartphones and social media in a world that seems to offer them few other options. Stranger danger fears leave them often sequestered at home. Or they end up shuttled from one extracurricular activity to another in the never-ending search for middle-class enrichment (and line items for their eventual college applications). They sometimes use social media as spaces to endlessly find themselves rather than to deepen ties with close friends, family, and local community. As I noted in my first book, “More and more children…experience autonomy as a freedom achievable only…by surfing online spaces.”

From Technical Limits to Technological Exits

When faced with seemingly technological problems, it is easy to reach for technocratic solutions, for policies tinker around the edges. No doubt that firmer limits, such as discouraging or prohibiting smartphones from the classroom or genuinely enforcing age restrictions for social media access, could do a lot of good for some kids. But, similarly for problem gamblers, the longer-term solution is to try to build societies in which pathological patterns of using smartphones and social media can be more easily resisted. Youth (and adults) need ways to exit social media-dominated lives, not simply new restrictions.

Long-time followers of Taming Complexity might already recognize where I’m headed. Just as I don’t think talk of limits and sacrifice are much help in addressing climate change, neither am I very optimistic about using sticks and carrots to keep young people out of one of the last free spaces that they have available to them. Instead, they need alternatives, more offline places where they can be kids, explore the world, and have some control over their own lives.

The advantage of providing “exits” rather than “limits,” is that we don’t need to know beforehand exactly how bad smart phones or social media are per se. It’s possible that Haidt is exaggerating the unique risks posed by these technologies per se, at least a little. They are probably one contributor among many to people’s mental health problems. Or, like problem gambling, they may be a sometimes self-detrimental escape for people who are already struggling in their offline lives.

In any case, creating exits saves us from doing all the highly contestable and often boring work of trying to discern the tradeoffs for punitive or potentially far-reaching policies, and from proving that the problem is bad enough to merit action.2 If people have genuine alternatives, they will do what makes sense for them. All we have to do is watch.

And, given that many people say they want to be less dependent on their smartphones and social media, supporting the development of exits would simply be responsive government. No need to ask technocrats for permission. No need to wait and see if the data on teen depression, anxiety, and suicide gets clear enough to justify action.

That said, getting to that point would require a lot of social science that we’re currently not doing enough of. For instance, what stops people from getting to know their neighbors well enough to trust letting their kids outside unsupervised? How might we de-incentive or free more people from the college application rat-race? In what kinds of physical spaces would young people actually want to hang out, and how can we get them built? What new forms of local community could more often draw citizens in highly individualized nations out of their homes?

By turning the question around from, “Are smartphones and social media making our lives worse and to what extent?” and toward, “How can we help people live more fulfilling lives?”, we can not only make social science far more useful to the average citizen, but also finally start fighting against having our societies almost unilaterally governed by the whims of technology firms.

To be fair, Haidt sometimes doesn’t do enough himself to explicitly distance himself from this interpretation.

I decided against harping too much about the limits of social scientific knowledge, but both Haidt and his critics tend to exaggerate how much limited data either vindicates or disproves different theories, often comparing data that are not just incomplete but probably incomparable, for they measure very different things and make very different assumptions about what makes for reasonable interpretation. Frankly, we’re awash in conflictual data. And everyone has an underlying story about the world shaping their social analysis. We’d be a lot better off if people were more upfront about those stories (and more intellectually humble as a result).