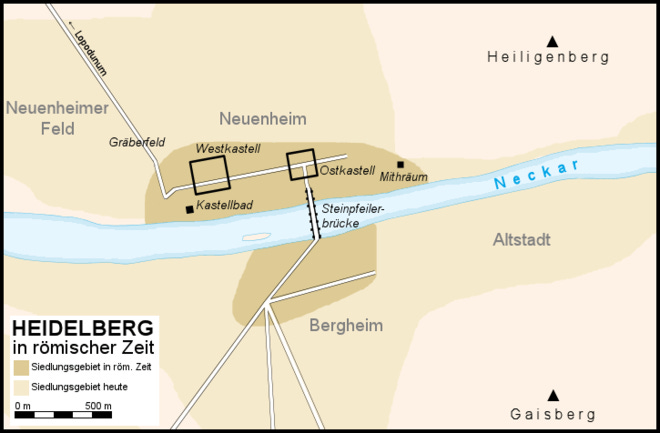

Heidelberg, Germany has often found itself at the crossroads of history. Two thousand some years ago, it was a far outpost of the Roman Empire. Although it was overshadowed by nearby Lopodunum (today Ladenburg), the town on the Neckar River eventually boasted a stone bridge spanning around 260 meters (850 feet), which fell into disrepair when Romans retreat in the face of Alemanni and Gothic attacks.

Germany’s oldest university was also founded there. In 1386, Elector Ruprecht I of the Pfalz worked to establish a theological center of learning after the Western Schism. Graduates from the French Sorbonne could no longer give Catholic services, because they pledged their allegiance to Pope Clemens VII in Avignon rather than Urban VI in Rome.

After World War II, the city became the headquarters of the American occupation force, and eventually a NATO command center. The story has it that the city was too beautiful to be bombed by the Allies, but it probably had more to do with the lack of industry. In any case, some 20 thousand American soldiers made their presence known in a region with only 150 thousand residents.

As interesting as these historical asides are, what I find most fascinating about the area around Heidelberg is its demonstration of an array of land use compromises. We often talk, especially in the United States, about having to make difficult tradeoffs when deciding where to live. “Downtown is great and all, but can you imagine trying to raise kids there? How do you get them to after school activities? Where can you find time away from all the hustle and bustle?” Such a conversation has probably playing out millions of times around water coolers or over barbeque grills.

But these are conversations that probably don’t need to be having. We could have it all, or most of what we want, if city planning more productively reconciled people’s seemingly conflictual desires over urban space.

Living in the Missing Middle

For now, I live in a suburb of Heidelberg called Neuenheim. With a population density of about 5,800 people per square mile, it’s not spectacularly dense. It roughly lines up with St. Paul, Minnesota or the urban core of Honolulu. But it’s roughly ten times the density of my hometown in New Mexico and twice as much as Albuquerque.

Despite being nowhere nearly as dense as city like New York but nevertheless far denser than the American norm, I enjoy no shortage of easy access to both amenities and nature. I can walk a few blocks to the local market square on a Saturday morning, letting my kids run in the nearby playground while I enjoy a cappuccino and buy freshly baked bread. My commute is a five-minute bike ride. If I need to go to a grocery store or pharmacy, or even see a doctor or a dentist, I have several within an easy walking or riding distance. And getting out of town is straightforward (the light rail is within a couple of blocks).

But that doesn’t mean that I don’t also the enjoy pretty much all of the advantages of suburbia. My own street is quiet and lined with beautiful trees. The narrowness of it means that nearly all car traffic is local. Almost every house is multifamily, but the ingenious design of these homes gives nearly everyone space to repose. My first floor apartment has access to the front yard, which is shielded from the street by bushes, trees, and a fence, while my upstairs neighbor gets the back. Nearly everyone has at least one spacious balcony on which they can enjoy dinner or their morning coffee.

This, of course, isn’t universally true. Germany does have its share of drab apartment buildings. And people living in a traditional Wohn- or Häuserblock would typically have to settle for shared access to an interior yard.

A person who wanted more privacy, however, could lease a Kleingarten from a nearby Schrebergarten club. These average about four thousand square feet, or one tenth of an acre. Leases typically cost less than a hundred euros per year, though you might spend several thousand to purchase the buildings on it. In addition to planting flowers, trees, and vegetable and fruit gardens, Germans erect tiny houses on their Kleingarten plots, turning them into pleasant places to watch soccer on the weekend or simply enjoy nature.

When my kids want more space to run, we have our pick of several playgrounds in the area. Each usually spitting distance from a café or ice cream parlor. If we want a stronger contrast, a couple kilometers to the East or West takes us to forested foothill trails or farmland. The farm roads are especially narrow, barely wider than a medium tractor. On weekends they are full of people walking, biking, and rollerblading. And there are no shortage of sporting clubs in the area, providing classes and teams to join for all ages.

After only a few short months here, the tired old debates that I heard incessantly in the US no longer make sense to me. There’s certainly a rough relationship between urban density and the kind of life that can be lived, but how cities are put together is far more important. More neighborhoods could offer nearly all of what most people could want from them.

Recreating Neuenheim

In places like Neuenheim, the complexity of the urban fabric developed incrementally, perhaps not too dissimilar to the emergent urbanism of Japan. No doubt that there are some rigid policies, such as those that development doesn’t encroach farmland or forests. And many of qualities of the town are a result of pre-auto age development. Yet even my hometown of Socorro, NM once looked a lot more like Neuenheim. The difference was that there was little opposition to transforming main street into a chain of build big box grocery stories, gas stations, and roadside motels.

I’m not motivated by a wistful nostalgia in making this point. A place that refused to adapt to changing transportation and economic realities over the 20th century would have sown the seeds of its own economic demise, like the cities and villages that became ghost towns when they were bypassed by the interstate. The issue is that progress was seen as an unstoppable juggernaut. Urban planning in the United States was largely the one-sided appeasement of fanatical automobility, when the demand to find space for cars could have spurred a more creative destruction and synthesis.

In Neuenheim and other German cities, the urban fabric is the outcome of decades of disagreement and compromise, of the ongoing tussling between conservativism and visions of progress. New constructions of glass and steel stand next to extremely old buildings. Gas stations and supermarkets can be found a few blocks from historic churches and town halls. Room for cars were made in the narrow European streets and then later reduced to once again make way for pedestrians and bikes.

The result was something that one could hardly imagine a professional urban planner being able to dream up. It’s too messy, too clumsy. Yet it seems to work far better than any rationalistic model in giving citizens what they need.1

The challenge before us in the United States is not to recreate the outcome of European urban evolution but the process behind it. How do we artificially set the preconditions that spur on an organic process of constantly renegotiating the urban fabric? How do we move from a static status quo, one characterized by extreme divisions between urbanists and NIMBYists, toward a place where urban compromises are possible?

The trap that we tend to fall into when discussing cities is to take a god’s eye view. That that is what maps seem to provide us is no doubt an instigating factor. Taking that perspective leads us to think in terms of setting city or neighborhood-wide zoning and building codes to try to enforce desired changes in the land. James C. Scott called this move “seeing like a state.” While rationalizing maps and models help decision makers grasp what they are trying to govern, relying on causes them leads states to fail to consider both local politics and citizens’ on-the-ground knowledge.

In this case, a rationalistic perspective can fool us into pining for idealistic redesigns of then cityscape when what we actually need is a deep understanding of exactly where and how urban changes can be made possible. Where can compromises be most easily elicited?

Take, for example, the politically fraught effort in many cities to simply allow duplexes and multifamily homes. The insistence on attempting that policy change across the entire city or in within a certain distance of transit can provoke polarized NIMBY. If even that policy seems incremental when looking at a city map, it may not feel that way at street level.

As a result, my recommendation would be for cities to start even smaller. Which units, blocks, or neighborhoods have the right mix of advocates, few outright enemies, and infrastructural malleability to create demonstration or pilot projects? Too often we fool ourselves into thinking that NIMBYism is something solved by rational debate, when proposed futures cannot be made less frighteningly uncertain by mere talk (or graphs and studies).

People reasonably want to see and experience a taste of what change will be like. And policymakers and advocates of change should more often see their primary task as offering skeptics exactly that.

A great example of this is the Passagen of the city of Leipzig. What they brilliantly demonstrate is that much of the value of urban spaces is in the perimeter of buildings, not their volume. By inviting pedestrians into the insides of city blocks and filling them with stores and cafes, Leipzig’s downtown core feels much larger than it is. Different city blocks become miniature malls and great pathways for escaping winter weather. Moreover, they boast an array of differently sized retail spaces.