This is part VIII in our now somewhat sprawling series on Elon Musk and what he represents about the way we govern innovation. Part I. Part II. Part III. Part IV. Part V. Part VI. Part VII.

It can be easy to talk about Elon Musk and criticize him for his many poor decisions, or his anti-worker policies, or his recent right-wing conspiracy promotion. Even people I’ve met who admire his companies have disdained the man himself. But is Musk really the problem? Is the issue merely that Elon Musk makes more money than his ideas are worth? Have investment markets simply picked the wrong billionaire? Or does the success of Musk hint at deeper problems in the financial systems which propel much of our society’s technological innovation?

No one is forced to invest in Musk’s endeavors. So it is difficult to see the current state of silicon valley tech investment as anything but irrational for pouring so much money into his companies. The aim of venture capital investment is to support high risk businesses that have high growth potential. This has traditionally meant betting on esoteric inventions that might revolutionize an industry. Instead, VC today is increasingly focused on firms and technologies with the potential for lock-in, that is, monopolization. The distinction is subtle, but the practical outcome is that more and more VCs are divorced from the actual performance of new technologies and the companies that make them.

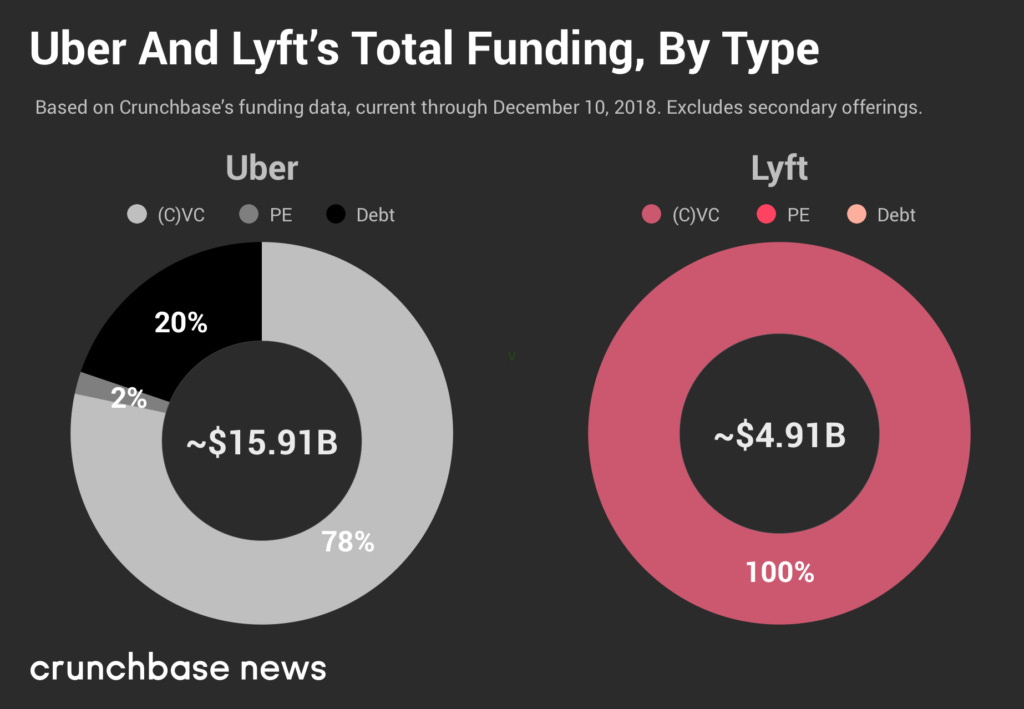

As we’ve pointed out in our discussion of lock-in already, ride share apps like Uber are prime examples of this trend. The cost of a ride is heavily subsidized by VC investment, and actual profits are a recent phenomenon that few firms enjoy. The industry’s struggles stem from their preoccupation with capturing the entire taxi-service industry. More realistic business practices and innovations must be thrown aside when firms also have to convince venture capitalists that they could eventually become “the amazon of transportation.”

Because this monopolistic speculation is, well, speculation, it is largely driven by the innovation myth. Musk’s companies are awash in capital not exactly on the basis of the objective strength of his ideas, but because of the mythos surrounding Musk himself. More generally, VC tends to accrue to innovators who look like venture capitalists (white, male, and wealthy) and focus only on what venture capitalists tend to think are problems. As Elizabeth MacBride asked in the MIT Technology Review, where is the funding for efforts to prevent or weather the next pandemic, better provide medicine to those suffering from drug addiction, or help low-income schools find better substitute teachers? Three quarters of all VC goes to software projects, which often can only promise to make our leisure time or other everyday tasks slightly more convenient, while leaving most of people’s real problems unaddressed.

This is part of why tech startups seem so frequently to just be reinventing a worse wheel. Musk’s idea for the hyperloop was basically a train but worse. Uber and Lyft are taxis, but worse. The company “Bodega” was just vending machines, but worse. Juicero was just a juicer, but worse *and* much more expensive. The vision for each of these was never to improve on existing technologies or ways of doing things. It was to create something that could lock-in, could monopolize, those markets.

At best, the result of investing this way is a colossal waste of money. Juicero wasted $120M in investments that could have gone to something that mattered. Not to mention however many consumers wasted $400 a pop on those things. All of that money could have, instead, been invested in a technology that actually improved people’s lives or met some currently undermet need.

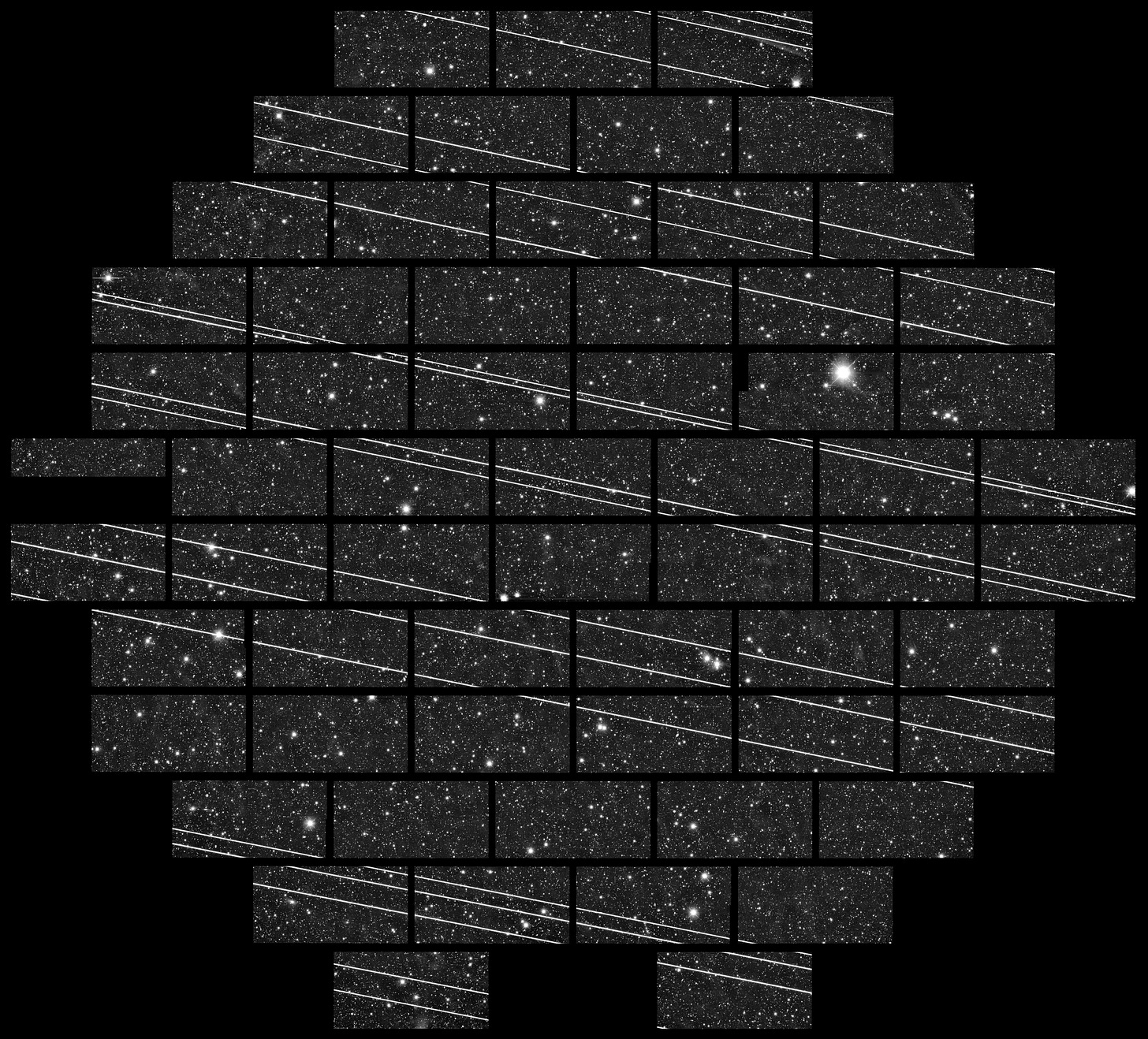

Worse yet, billions of dollars get funneled into projects that are actively harmful to humanity because the dominant personalities that support them convince investors that they may actually succeed at cornering the market. Uber, Lyft, and similar rideshare apps replace decent jobs driving taxis with much more precarious driving jobs, are less safe for passengers than taxis, and make traffic and transit worse. Musk’s hyperloop was never realistic from the start, and he may have proposed it for the sole purpose of hurting rapid transit projects like California High Speed Rail. And the proposed network of 40k new Starlink satellites may enable SpaceX to take over the ISP market (and if we still want to take Musk at his word, also help address digital inequality), but it could also render astronomical observation impossible and create enough space trash and broken satellites to render low Earth orbit completely useless.

The current VC system is one where investors try to figure out which new technologies will be locked-in in their respective markets by looking at the mythos of the people helming the companies. The result is, best case, throwing good money after bad. The worst case, however, may actually be if the investment is successful and the rest of us now have to live with the consequences of whatever men like Musk dream up. And we easily forget about all the other great ideas and talented technologists who aren’t getting invested in as a result. How many potential technological breakthroughs have been left underfunded because another billion dollars went to a Silicon Valley billionaire’s vanity project?

If we want a system of investment in innovation to yield different results, we can’t just get rid of Elon Musk and expect everything to change. While Musk’s wealth, seemingly insatiable desire for popularity, and highly public blunders vis-a-vis twitter (X.com) all make him the perfect poster child for this discussion, we are under no illusions. If Musk gave it all up today, it would just be someone else tomorrow. The question to ask is, what can we do to disincentivize this sort of waste and harm from new innovations? How can we instead incentivize innovations that serve more people more of the time?

The next installments in this series will thus move away from Elon Musk and instead start to examine some of the alternative ways to fund innovation. Sovereign wealth funds, state ownership, worker coops, environmental, social and governance (EGS) based investing, and other mechanisms are all going to be under consideration. We don’t expect that any one alternative should outright replace our current system of investing. What we hope to do instead is to consider the tradeoffs and potential benefits of alternative systems and how they might fit in or incrementally replace certain parts of the VC system. Please let us know if you have any mechanisms you’ve heard of that you want us to think about and discuss! This is going to be a learning experience for us as well!

> The next installments in this series will thus move away from Elon Musk and instead start to examine some of the alternative ways to fund innovation. Sovereign wealth funds, state ownership, worker coops, environmental, social and governance (EGS) based investing, and other mechanisms are all going to be under consideration.

If the SWF installment is any indication, this promises to be a mind blowing series.