Population Collapse!

What collapsology can tell us about declining fertility, and what it can't

In science fiction depictions of worlds without children, the cause human infertility is almost always external. Children of Men envisions a society where an unknown agent has prevented the birth of babies for 18 years. The culprit in Kurt Vonnegut’s dismal novel Galapagos is a mysterious microorganism. It is telling that science fiction authors are able to dream up the end of the world but can’t fathom that societies’ populations would shrivel because people simply decided to stop having so many children.

For decades, we have been told that the world is imperiled because of too many people, not too few. Malthusians, such as Paul Ehrlich have foretold population bombs, waves of mass starvation caused by people getting too busy, too often. As a result, many people find it difficult to imagine why fewer human beings could be problem. Won’t depopulation usher in human civilizations that treat far more lightly on the Earth, finally restoring the ecological balance disrupted by human overbreeding?

For those who take the issue to be a serious problem, things take on an existential tone. Elon Musk argues, "population collapse due to low birth rates is a much bigger risk to civilization than global warming." In this view, we face far more than a simple demographic changes or decline but rather a potential catastrophe, a civilization-level threat to the structures that holds societies together.

To make sense of the risks that depopulation poses and why it is happening, we should learn from collapsologists who have wrestled with the question of civilizational resilience. Although we can get a lot of insight from applying the lessons learned from Imperil Rome and overexploited pastures, we will have to confront the reality that we increasingly live a fundamentally different kind of human civilization, and that increased fertility isn’t something we can simply legislate into existence.

Babies and the Costs of Civilizational Complexity

Civilizational collapse has long been an object of fascination. Jared Diamond’s 2005 Collapse was a New York Times bestseller and can be found in the living rooms and libraries of most everyone who still reads books. Diamond’s argument, however, that societies fail because they don’t to adapt in the face environmental degradation, external threats, and a changing climate really isn’t an explanation of collapses, but merely a description of them. A civilization that falls apart failed to make the necessary changes for survival almost by definition. How is it exactly that societies veer on a path toward self-destruction and fail to get off of it?

Anthopologist Joseph Tainter had recognized this same failing with theories of civilizational disintegration decades earlier. Blaming the demise of the Roman Empire or Mayan Civilization on catastrophe, intruders, political mismanagement, or other factors, Tainter argued, merely describes collapse rather than explains it. Complex societies have often weathered such disruptions without falling apart, or have even come out of a crisis or conflict stronger than before. If a theory of collapse can’t simultaneously explain societal resilience and growth, then it may be a “just-so” story, an unverifiable narrative how the past came to be.

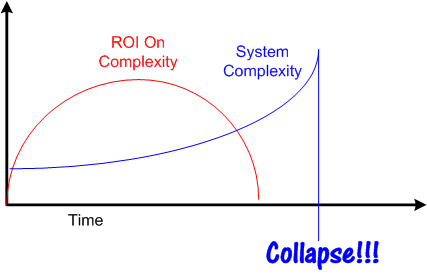

Tainter’s alternative, developed in his 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies, was to view civilizations as complex systems “maintained by a continuous flow of energy…sufficient [in amount] for the complexity of that system.” Tainter argued that societies grow more organizationally complex as they go about solving their problems, and that complexity can be expensive. Agriculture solves a number of the limitations of hunting and gathering, but introduces new demanding tasks: animal domestication and husbandry, seed and food storage, and the collective organization of planting, irrigation, and harvest. The fact that the transition to agricultural societies brought with it new classes of bureaucrats, artisans, and other elites is a result of not only the newfound energy surplus that could support them but also of the fact that these new specialized workers were often necessary to manage the society’s new and higher level of complexity.

Civilizations falter when a mismatch emerges between the costs of complexity and the available energy. Ancient Rome essentially ran on solar energy, which is to say agricultural goods, largely acquired by conquest. When the complexity costs of military expansion exceeded the gains in plunder, Imperial leaders found themselves trapped. They had a burgeoning military and tax bureaucracy, along with far too many Roman citizens living on the imperial dole. When plagues decimated the peasant population, the empire’s fate was sealed.

Faced with a shrinking treasury, elites responded by debasing the currency and raising taxes on the rural population. Those who couldn’t pay ended up being jailed, selling their children into slavery, or abandoning their fields, which only made the underlying energy deficit worse. Many citizens during the empire’s twilight actually welcomed barbarian invaders, because they wanted desperately to be relieved of the burdens of a Roman state that had lost all legitimacy. By then the costs of citizenship far outstripped its benefits.

Modern societies have been able to achieve spectacularly high levels of complexity for two reasons: fossil fuels and computerization. The former provided unprecedented energy surpluses, most fossil fuel extraction returns 10 to 40 times the energy invested, while computerization has made greater levels of complexity far less costly to manage. But focusing on energy and complexity can lead us to overlook the reality that labor is still necessity to make the society run, a factor that collapsologists underemphasize because most historical societies struggled with the challenges of complexity amidst rapidly growing populations, not shrinking ones.

Many developed societies may eventually find themselves a similar position as the ancient Romans, except the issue may not be a bloated military and tax bureaucracy but rather simply an imbalance in numbers between those who work to those who can’t. According to the latest UN projections, declining fertility in South Korea will lead to half the population being over 65 by 2083. Instead of a little over two workers supporting every dependent, measured as people under 14 or over 65 years old, each working age South Korean will have to support almost one and half dependents on their own.

An abundant 21st-century depends on maintaining surpluses of, hopefully low carbon, energy. It also relies on an economy supplied with sufficient labor to both make things and manage the complexity of the overall system. In order to counter the weight of a growing population of dependents, technological advancements in the ensuing decades would have to ensure that future workers are several times more productive than they are today just to maintain current living standards. But a shrinking consumer base undermines the both economies of scale and the growth potential necessary to attract capital investments to artificial intelligence and automation. As a result, future technology-driven productivity gains are far from guaranteed.

Later this century, workers around the world could end up like Roman citizens in the dying days of the empire: Hoping for an escape from the growing burdens of supporting a sclerotic society.

The Fertility Freerider Problem

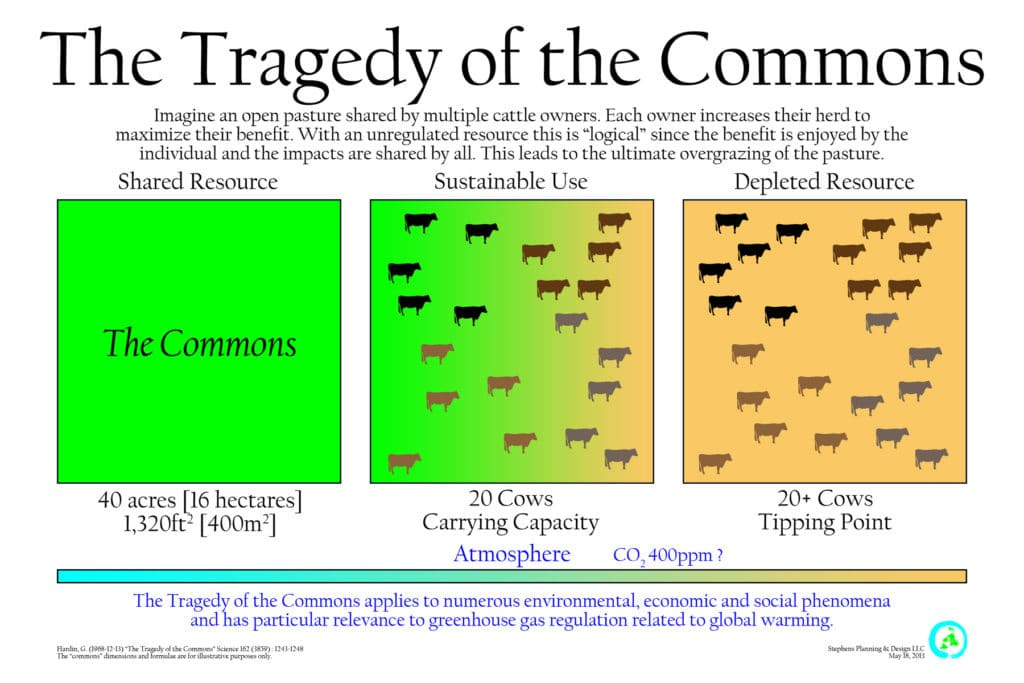

Imagine a luscious, green pasture. And imagine that you’re a cattle farmer in a peasant village. Normally you graze a dozen animals each year, enough to provide milk and meat to your family and to sell a few at market. Rains were good this year, so it seems silly to let it go to waste. You buy an extra calf from a nearby village to graze on the pasture, hoping to earn enough to really get ahead this year. Surely one measly cow couldn’t hurt. The trouble: Your neighbors all did the same thing. The grassland gets overgrazed a month early and the village’s cattle are now too emaciated to sell at market. Everyone has a hard winter.

This is an example of the “Tragedy of the Commons,” described by ecologist Garrett Hardin as a process by which individual choice perversely leads to collective ruin. Hardin was not really concerned with the overuse of pasture. He used it as a metaphor to warn of the dangers of overpopulation, a worry that now seems quaint.

Like other ecological catastrophists of the era, Hardin saw Malthusian disaster as almost inevitable, embracing fairly regressive ideas about immigration and the right to procreate. In his view, the welfare state was ill positioned to “deal with the family, the religion, the race, or the class (or indeed any distinguishable and cohesive group) that adopts overbreeding as a policy to secure its own aggrandizement.”

In any case, Hardin’s story is meant to illustrate the situation that arises when individual incentives lead people overuse a collective resource, depleting it in the process. In essence, the herdsmen believe they can freeride on the responsible, conservation-minded behavior of their neighbors, not realizing that others are following the same attractive, but ultimately misguided, logic.

Modern pension systems were developed to solve a freerider problem. Prior to their existence, old age care depended on a person’s and luck in having children, ensuring that they survived into adulthood, and persuading them to return the favor later. There’s no doubt that today’s retirement arrangements help prevent the previously widespread moral travesty of senior poverty.

But those systems ended up inadvertently creating a new kind of freeriding. Most pension programs are “pay-as-you-go” (PAYG) systems, which means that today’s beneficiaries are being supported by the current crop of workers. These systems’ foundational assumption is that future generations will exist in sufficient numbers to support each new cohort of retirees.

Even private retirement plans, though not exactly PAYG systems, are likely to eventually stagnate in the face of shrinking societies. A 401k produces a healthy return only so long as the economy experiences dynamic growth. Although the effect of population aging on economic growth remains a matter of debate, one Deutschemark analysis anticipates more static economies, with fewer new firms entering markets and experiencing lower levels of profitability.

In light of these dynamics, retirement systems start to look like a pasture suffering a freerider problem. At some level, they rely on some portion of workers having children in sufficient numbers. But the increasing number of “childfree” citizens, at least among the middle and upper classes, do not bear the burdens of bringing a new generation of workers into existence, instead being enabled to save for a more comfortable retirement. Unlike in centuries past, modern childrearing is a pure cost. No longer do kids bring income into the household.

The economic benefits of new generations, moreover, accrue diffusely to society at large. In one study’s estimate, European parents effectively pay an additional metaphorical tax (paid in time and money) to raise the children necessary for societies to function, one several times larger than their country’s value-added taxes. In effect, modern societies transfer wealth from parents to non-parents and future generations. No doubt the people who forgo children have not consciously decided to free-ride on others, but it’s the invariable result.

The authors of a 2015 NBER working paper blamed the majority of the United States’ fertility reductions since 1920 on pension programs and private retirement savings accounts. A study on Brazil’s 1991 decision to expand its pension system to the rural sector found that by 2010 the pension wealth among these workers had tripled, but at a cost of an average of 1.3 fewer children born to each rural woman.

The ironic thing about Hardin’s thought experiment about grazing cattle is that commons threats seem to be mainly modern creations. For instance, space-faring nations’ collective mismanagement of debris threatens to make near earth orbit useless and rocket launches evermore dicey. Traditional societies weren’t actually so short sighted. Or, at perhaps more likely, they recognized and corrected mistakes before tragedy struck. As 2009 Nobel Laureate Elionor Ostrom found in her research, people faced with managing a commons, whether it be a desert irrigation system, fishery, or forest, typically developed collective rules and institutions that prevented overuse tragedies.

The traditional irrigation systems, or acequias, that remain is some parts of New Mexico, for instance, inherited from the Spanish a democratically run system for managing ditches and allocating water both in good times and during droughts. In Valencia, Spain there’s even a weekly “water court”, a thousand-year old tradition in which eight farmers dressed in black adjudicate infractions and conflicts that can’t be dealt with at the local-level. These institutions have held stable for hundreds of years on both sides of the Atlantic.

It should go without saying, however, that fisheries, forests, and irrigation systems strike most people as not at all analogous to wombs. Even if future generations are a common resource that we all depend upon, governing fertility as if it were a commons is probably politically infeasible and questionably desirable. Maine lobstermen safeguard their common fishery through the implicit threat of social sanction, and attacks on defectors’ traps or even outright violence, when shaming doesn’t work. Institutions to protect a commons need to be built upon a vision of common future, a social community, that in turn legitimizes rule-making and the use of shaming and other punishments for violations. In today’s individualistic societies there is no social glue that would justify such an extreme incursion into people’s personal choices.

The best we could hope for is to turn childrearing into what is called a “club good.” Essentially this involves putting fences around a common. Costco or Sam’s Club stores are an example of this. People pay for a membership and enjoy special deals on electronics and exorbitantly large quantities of kitchen staples. In this case, however, people would be joining “club parent” by having kids, and their governments would offer them a higher-tiered pension, give them access to additional public services (beyond just free children care), or award significant tax breaks to those currently raising children. They would go further than the current child tax deduction, significantly reducing the costs of having kids.

Even this less punitive approach may strike some citizens as unfair, given that many people don’t have children for reasons outside of their control. We might worry about the unintended consequences of overamplifying extrinsic motivators for having children. Demographer Nikolai Betov worries that tying parental benefits to the number of children born “are likely to be seen as controlling and thus might undermine the intrinsic motivation for childbearing.”

Elite Overdemand

While seeing fertility as a commons uncovers a failure of governance, doing so doesn’t help us understand why birth rates have dropped so precipitously around the world. It is doubtful that freeriding on pension systems is the main motivator. For many people debating having kids, the question is more about whether they can adequately provide for them. Childrearing can be seen as beset with a different kind of collective action problem, one created by inequality and increased competition over economic opportunities.

This is the area where the debate about population collapse is often at its most confused. “Children are simply too expensive,” says a middle-class person who is far richer and enjoys more luxuries than all of their ancestors put together. Even though some of us experience increased job precarity, and there seems to be a shortage of starter homes, the portion of American households making over $100k (inflation adjusted) has roughly doubled in the last decades to over 40 percent.

My point in recognizing that irony is not to dismiss such sentiments are misinformed, but, instead, that they need to be understood within their broader context. The problem is not that children have become too expensive per se, rather incomes increasingly seem insufficient to pay for the kind of lifestyle and preparation for adulthood that parents believe they must now provide.

Again, we can return to South Korea. A study by economists Seongeun Kim, Michele Terlilt, and Michul Yum finds that poorer families have fewer children and more likely childless, because of the country’s cutthroat educational culture. To be a successful student in South Korea demands attending hagwon cram schools on evenings and weekends. The children of the most affluent will attend classes until as late as midnight. Poorer families’ lower fertility, argue the researchers, is simply them responding to economic realities. They cannot afford to have a big family and ensure that their children can keep up with their richer classmates.

It is here that we run into another theory of societal instability. Russian zoologist Peter Turchin has argued that “overproduction of elites” partly drives many societies into decline. Whether it be Occupy Wall Street, Arab Spring, or political revolution, the most fervent agitators have often been would-be elites suffering from frustrated ambitions.

In the case of Occupy and Arab Spring, it was college graduates facing bleak employment prospects. Many of the French revolution leaders came from the growing merchant class that was being shut out of political power. Societies are destabilized by an overproduction of elites, the idea that when upwardly mobile citizens face frustrated aspirations, they man the barricades and leverage opportunities to bring down their more successful colleagues.

As Turchin argues in his book End Times, as college degrees no longer confer elite status by default, a kind of academic arms race as emerged, one justifying getting ahead by any means necessary. Increased competition, in turn, makes childrearing increasingly costly for everyone.

But this doesn’t really seem like too many elites but rather an increasing demand for elite spots. People living in a world of abundance that would have astounded their grandparents can say, “Children are too expensive,” because they seem to have come to believe that a life that doesn’t feature a solid chance at the upper quintiles of society is no longer worth living.

We don’t have hagwon’s in the United States. Instead, parents strive to buy more expensive homes in better school districts, save for college tuition, and invest time and money in extra-curricular activities to give their kids an edge in university applications and a better shot at scholarships. Youth sports, in turn, have been transformed from sandlot baseball and recreation league soccer into a private equity-run “travel teams” that extract countless hours and thousands and dollars from parents. The fact that American couples are having children later and later, which restricts childrearing window available to them, is likely a partly due to worries about the costs of giving their children a running start in the meritocracy.

The Domestic Arms Race

Another oft-cited cause for fertility decline is the failure of husbands to do their fair share, leaving mothers stretched too thin to want more children. This is probably the case in countries like South Korea, where the gendered division of household labor remains a gaping chasm despite women’s entry into the workforce. Many people point to gender-equalizing social policies within Scandinavian countries as an answer to America’s demographic aging, neglecting the fact that their fertility rates are even lower than ours. In any case, many data sources suggest that American women still do about an hour more, on average, per day than men.

Such numbers come from time-use studies, which ask people to track their daily activities for a randomly selected day. There are limits to the amount of confidence that we should put in them, because they vary in terms of how well they capture traditionally male forms of housework, which tends to be more episodic. A random call from a Bureau of Labor Statistics worker asking me what I did on Tuesday wouldn’t capture how I spent three weekends in a row designing and hanging cabinets for my wife.

There are also tricky complexities regarding how survey designers and respondents define different categories of activity. Does watching Netflix while (more slowly) folding laundry count as leisure or housework? Is a father periodically dozing while his toddler plays nearby doing childcare or just being inattentive? Under what conditions does bringing your kids to a backyard birthday party count as socializing rather than childcare? All we can really say is that current metrics show men lagging behind women in terms of time spent doing routine domestic chores and parenting.

The irony, however, is that husbands are doing more than ever. The first big jump in men’s’ time spent doing childcare happened in the mid-90s (at least in the United States). Gen X fathers roughly doubled their involvement with their kids’ lives in comparison to their Boomer dads. The trope of man-baby husband who can’t lift a finger at home to help seems to be far more difficult to budge than men’s actual sharing in the burdens of domestic life.

Men’s increasing involvement, however, has failed to result in domestic equality, though not for lack of trying. The problem is that fathers have had to deal with a moving target. Mid-90s mothers in the United States didn’t see their more involved husbands and decide to “lean back.” They responded by spending an additional 60% more time parenting. And this patterns looks to have been the rule around the world: increasingly engaged fathers have come along with mothers doing ever more household labor. But there remains the question of why women haven’t been able to reduce their own burden. Why has increased gender equality over the last decades only resulted in more work for mother?

In Optimal Motherhood and Other Lies Facebook Told Us English professors Jessica Clements and Kari Nixon argue that modern mothers are trapped in a kind of cult. A barrage of articles, memes, inforgraphics, and social media posts (see below) constantly reinforces the idea that there is a perfect form of motherhood, that domesticity and childrearing is something that, with the right information, women can optimize. But ever growing expectations, such as to exclusively breastfeed or to create completely hazardless spaces for their baby’s slumber, have been paired with the loss of community support. Such support, in any event, wouldn’t be welcome anyway. “The Optimal Mother,” contend Clements and Nixon, “must perfect her family, and she must do so in a vacuum, because perfect women shouldn’t need help.”

A study reported on in Psychology Today appears to corroborate the thesis of Optimal Motherhood. They found that single mothers do less housework than married ones. No doubt it’s possible that some husbands create more work for their wives, but the researchers contend that the difference is better explained by mothers trying to meet an impossibly high standard of domesticity. Removing the husbands from the equation eliminates part of the pressure to “perform” as a wife and mother.

But the persistence of the cult of the optimal mother can’t be simply blamed on fathers’ demanding too much, either explicitly or simply serving as an unintended symbolic foil for motherhood. Unrealistic guidelines that women get from organizations like the American Academy of Pediatric or La Leche League don’t help. But the fact that motherhood has become an increasingly exacting and individual responsibility is largely because of other women.

Online discourse in mom’s groups dealing with issues like post-partum depression, breast feeding, and safe sleep often shames women for failing to achieve perfection. To take medicines for depression, to be unsuccessful in breastfeeding, to breastfeed too long, to co-sleep with your baby, or to let your children “cry it out”, nearly all parenting approaches provoke online judgement, the message that mothers are failing their sacred duty.

Whether driven by a hyper-meritocratic culture or the cult of optimal motherhood, the domestic sphere has increasingly taken on the qualities of an arms race. International arms races are usually ended by treaty. While South Korean economists contend that child curfews and employing a 22 percent tax on private educational spending could take the edge off of their meritocratic culture, it is difficult to imagine politically feasible policies that could push parents to lower their aspirations for their children or for themselves as mothers.

The Limits of Technocratic Fertilization

Writing about Emperor Augustus’ efforts to increase fertility in ancient Rome, historian James Field argued that “the central error…was his assumption that childlessness is a legislatable phenomenon.” And he had a point. In ancient Rome, a large class of professional spies eventually emerged to detect citizens trying to evade laws that punished the childfree. And tax laws that essentially exempted the poor from taxation, if they had children, proved insufficient.

While no doubt tied up with economic incentives and various practical considerations (i.e., good schools, proximity to family support), the decision to start a family is really a matter of vibes. As the Japanese committee member that Colin quoted in his post put it, “A society people want to bring children into is one in which they feel cared for, respected, treated with dignity—not one in which they are reduced to a number.”

We’ve already seen some of the ways in which modern society, while increasingly materially abundant, has robbed parenthood of its good vibrations. Its joys are drained by anxieties about meritocratic achievement. Lazy days hanging out with kids in the backyard have been replaced by long highway commutes to enrichment activities. Social media sends us into spirals of doubt, while also making it seem as if we’re always destined for failure. Occasional feelings of online connection are undermined by the overbearing presence of judgement.

It is no wonder that the prospect of collapsing retirement systems, stagnant economies, and the potential return of widespread senior poverty isn’t enough to make us make more babies. What would it take for modern parenting to seem a bit more dignified, for modern people to believe that we are rearing offspring not for an uncaring world that reduces us to a number but rather for one that feels a little more like a community? Where our civilization has gone wrong and how it might be great (for parents) again will be the focus of the second part of this article series.