From Samurai, to Salarymen, to Shut-ins

Depopulation and the Crisis of Masculinity in Collectivist Japan

Among the chattering classes, overpopulation is out and depopulation is in. In a twist on Frederic Jamesons’ classic line, Dotson recently wondered why it is easier for us to imagine the end of the world at the hands of aliens, robots, bacteria, and most recently fungus, than to imagine that civilization ends because … of our choices. Nothing comes to kill us—we just choose to stop having children.

Raised by back-to-the-land hippies, I always thought that overpopulation was the real problem. In fact, I never even considered depopulation to be a “problem”—I saw it as a “solution” to the bigger problem of environmental collapse.

So, as Bouchey encouraged us to ask, I have often wondered: Is a depopulating Japan really such a bad thing?

Consider the numbers. Japan is roughly the size of California, with mountains making much of the country uninhabitable, yet its population is 120 million—three times that of the Golden State. Its economy is also slightly bigger, vying for 4th place worldwide, yet it boasts social metrics that seem impossible for the richest blue state to achieve: near-zero gun violence, homelessness, and drug overdose deaths, with traffic fatalities a tiny fraction of the USA’s rate.

So wouldn’t 80 million people still be plenty?

The 2040 Problem

The problem is that “depopulation” is really a demographic crisis, wrought by an unsustainable ratio of young people to old.

You see, not all population declines are created equal. The different varieties of depopulation each have a different demographic impact on the crucial young/old ratio. In an event like the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 80 years ago, a more-or-less random subset is subtracted from the population. The crucial young/old ratio stays the same. By contrast, an event that disproportionately impacts the elderly, like the COVID-19 pandemic, can increase the ratio of young to old folks.

For Japan, however, the problem is on the supply side. It’s really a debirthing crisis. This is skewing the ratio in a direction that no society has much experience with. Soon, old folks will outnumber the young—for the foreseeable future.

Why is that a problem though? Beyond the obvious pension obligations, elderly populations require intensive care—medical attention, assistance with activities of daily life, and eventually end-of-life services. The Japanese government estimates that soon, 1.5 working-age people will be required to support 1 elderly person. This demographic of working-age people has been shrinking for decades, however, and is projected to shrink at twice the current rate in the 2030s. Barring miracles or catastrophes, when Japan’s elderly population—the longest-lived people on Earth, a testament to the country’s remarkable post-War achievements—peaks in 2040, there simply won’t be enough young people to support them.

If it were only a matter of tax revenue shortfalls and depleted budgets, perhaps the government could borrow money to stave off the worst of it. What makes this a full-blown crisis is that—again, barring a miracle or catastrophe—there will not be enough people to staff nursing homes and hospitals.

This is called “The 2040 Problem.” It isn't Godzilla rising from Tokyo Bay in a cloud of radioactive steam, but it's headed straight for Japan with perhaps greater destructive potential.

And like that fictional beast, born from nuclear hubris, this demographic monster is the unintended consequence of Japan's own post-war transformation. The difference is that after destroying Japan, Geriatric Godzilla won’t stop—it’ll lumber on toward every developed country on the planet.

The Samurai’s Last Stand

To understand how Japan reached the precipice of this demographic crisis, we need to excavate the peculiar transformation of Japanese masculinity after World War II, and sort out how a thousand-year-old warrior culture was dismantled after being defeated.

When General MacArthur's forces arrived in devastated Japan, they launched an ambitious social engineering project: To transform a militaristic society that had terrorized Asia into a peaceful democracy. Though it was a success in important regards—a rare exception to US post-war reconstruction efforts in later decades—the methods were sweeping and, in retrospect, culturally devastating.

After completely disarming the Japanese military, the American occupiers declared the martial arts—and even traditional kabuki theater—to be “bellicose,” and mandated their transformation into harmless “sports.” This bit of cultural surgery explains why you've probably heard of karate and judo, martial arts practiced with bare hands, but not, for example, sojutsu, the traditional art of fighting with spears, or naginatajutsu, the way of the halberd.

The occupation banned swords and firearms entirely in 1958. The way of the sword, which had shaped samurai consciousness for centuries, survived only as kendo, a sport involving bamboo sticks and protective padding. An entire cultural ecosystem that had provided meaning, identity, and pathways to honor, respect, and dignity for Japanese men was systematically dismantled in the name of peace.

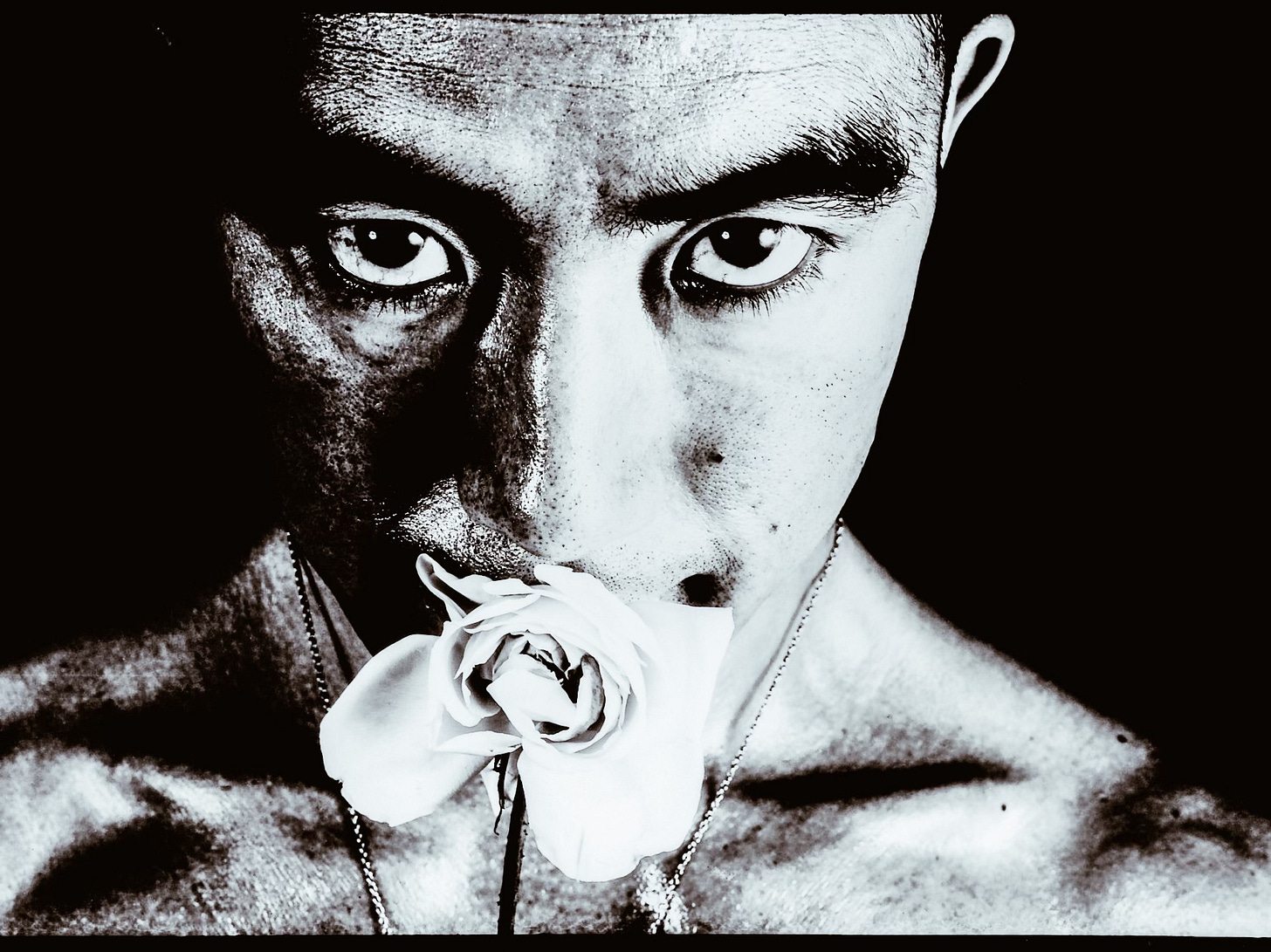

In the following years, the prominent novelist, bodybuilder, and cultural critic Yukio Mishima warned prophetically that the American occupation had “feminized” Japan in ways that would prove catastrophic. His theatrical style, rumored homosexuality (despite being married with children), and eventual ritual suicide in the the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japan Self-Defense Forces made him easy for contemporaries to dismiss as an eccentric provocateur. But his warning proved prescient: The systematic emasculation of his nation would generate unforeseeable consequences that would haunt Japan for generations.

The American occupation thus presented Japanese men with a new existential crisis in the post-War years: How does a man become a man when traditional forms of masculinity have been legislated out of existence?

Birth of the Salaryman

The answer was by training in a new dojo: the office.

Serving in the bureaucracies of government, reworked into a progressive democracy by Roosevelt progressives, and corporations, restructured from transformed from traditional feudal zaibatsu conglomerates into the modern keiretsu networks, became the new route to manhood.

The spirit of the samurai was transmuted, and the “salaryman” was born. He expressed his masculinity not through martial prowess or military valor, but through extreme working hours, unwavering loyalty to his company, and deep dedication to family and community.

The post-War corporation too was transformed in a similar process of cultural alchemy, replacing the han or familial clan as the organizing principle for collective social life. A full-time position with a company was not, therefore, mere employment—it was a sacred calling; a position for life that echoed the feudal bonds between a samurai and his lord.

It was a brilliant cultural adaptation. Where other defeated nations might have languished in resentment and despair, Japanese men found new purpose and dignity in this re-conceptualized masculinity. The salaryman could support his family as the sole breadwinner while simultaneously contributing to the reconstruction of his devastated nation. The way of the sword became the way of the spreadsheet.

But historical sketch of the what and how raises an important question: Why didn't Japanese men, crushed by atomic weapons and stripped of martial pride by foreign occupiers, collapse into bitter resentment? By contrast, all it took for American men to slip from the noble ideals of the “Greatest Generation” into toxic masculinity, deaths of despair, and inchoate fascism was a couple decades of de-industrialization.

The answer lies in how masculine identity is constructed differently in different cultures.

Two Types of Men

The anthropologist Ruth Benedict, recruited by the U.S. government during World War II to decode the psychology of an enemy that baffled American strategists, produced one of the most insightful cross-cultural analyses ever written. Her 1946 masterpiece, The Sword and the Chrysanthemum, was researched entirely from American soil—Benedict never set foot in Japan—yet proved so penetrating that it sparked an entire academic field of Japanese self-examination called nihonjin-ron ("theory of Japanese-ness").

One of her many insights concerned the fundamentally different ways individualistic and collectivistic cultures construct masculine identity. In the individualist USA, she argued, manhood is about personal autonomy and freedom from constraints. American cultural mythology celebrates cowboys and pioneers, men who escape social obligations to pursue individual destiny; men who resent going back to the “ball and chain.” Manly men therefore experience family, children, and the obligations that come with them as a loss of freedom.

This is why American culture developed institutions like the Elks Lodge, Shriners, and even the modern "man cave"—as spaces where “men can be men” outside the confines of hearth and home. While roaming the prairie and sailing the open seas have given way to elaborate video games and fantasies of space travel, expressions of individualist masculinity still involve escaping responsibility, not embracing it.

In collectivist Japan, however, Benedict found a starkly different form of masculinity. Here, manhood was measured in the number and depth of social relationships a man could successfully sustain and honor. Family wasn’t a feminizing constraint—it was the foundation, anchoring a man’s ties to community and company. Each subsequent relationship represented additional layers of responsibility that positioned the man as a more central hub within the collective society.

Social obligations, then, were not a loss of freedom, but a gain of responsibility. They added up to a relational, syncretic masculinity. A man's web of duties to company, community, extended family, and ancestors represented accumulated social capital; proof of his capacity to handle the complex demands of mature manhood. From this perspective, the American cowboy's "freedom" appeared not as admirable independence but as adolescent dereliction of duty (giri), behavior that invites social shame (haji) rather than respect.

Japanese Masculinity and its Discontents

Of course, not all Japanese men bought into this ideal. Even century ago, Japanese writers recognized that the collectivist expectations of their traditional culture conflicted with the new expectations of modern/Western individualism.

For instance, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, author of the stories that inspired Kurosawa's Rashomon, parodied the collectivist ideal of masculinity in his 1927 novella, Kappa, a dystopic critique of Japanese society thinly-disguised as a fictional account of the turtle-like river creatures of folklore. In kappa society, men have to carry their entire family—everyone from wiggling infants, and demanding children, to aging parents and infirm grandparents—on their back whenever they venture outside their homes.

Silent with strain, Akutagawa’s kappa-men stagger through their world as human pack animals, reduced to stumbling support-vehicles for their dependents. The physical burden serves as metaphor for the psychological weight of collectivist masculinity—something Akutagawa must have felt, and rejected, when he committed suicide the same year the book was published.

Two decades later, Dazai Osamu’s 1948 novel No Longer Human took the opposite approach, rejecting collectivist masculinity entirely in favor a profligate individualism that proved indistinguishable from narcissistic nihilism. His protagonist pursues absolute personal freedom through alcohol, women, and artistic pretension, only to discover that individualism without social bonds leads to spiritual death.

Dazai also killed himself upon his book's publication, suggesting that neither extreme collectivism nor extreme individualism offered sustainable models for Japanese masculinity.

The Miracle Economy

Despite these artistic warnings about the psychological costs of Japanese social expectations, most men of the post-war generation channeled their energies into national reconstruction. The results were nothing short of miraculous.

Rising from radioactive ashes, Japan became the world's second-largest economy within a single generation. In 1964, just under two decades since B-29s had reduced Japanese cities to rubble, the country launched high-speed rail service and hosted the Olympics. By the 1980s, it was threatening to overtake the US as the global economic hegemon. Japanese products conquered international markets through superior quality and innovative design. Cheap, reliable Honda and Toyota automobiles humiliated Detroit's Big Three. Sony's Walkman revolutionized personal electronics. Casio democratized digital technology with affordable calculators and watches. Nintendo systems invaded American homes. Japanese interests bought up iconic American properties like Rockefeller Center.

Industrial policy and American Cold War support certainly played important roles, the driving force behind this "Miracle Economy" was undoubtedly human: the tireless army of salarymen and their distinctive form of collectivistic masculinity.

For decades, this system delivered both spectacular material prosperity and psychological satisfaction. Japanese men had found a way to honor traditional masculine ideals while building a peaceful, prosperous society that avoided the militaristic disasters of the past. It seemed like the perfect synthesis of ancient values and modern realities.

Then, with a pop, all that was solid melted into air.

The Bubble Bursts

For reasons too complicated to get into here, in 1992, Japan’s miracle economy collapsed.

The shockwave knocked down a generation of kappa-men, and with them, their families. The 1990s were called the “Lost Decade”—though the economic and psychological fallout persists in various forms to this day.

The optimism of the miracle years—now remembered as the “Bubble years”—evaporated almost overnight. The collective mission that had sustained Japanese masculinity for nearly half a century—reconstruction, development, building a peaceful and prosperous society—had been mostly achieved. But for what? What was the point of decades of sacrifice if everything could vanish when the Tokyo real estate markets had an asset bubble?

The psychological devastation paralleled the economic destruction. Beyond the unemployment statistics, layoffs left proud salarymen too embarrassed to tell their families they had lost their jobs. A cottage industry even emerged offering fake receptionists who would take calls from confused wives, explaining that their husbands were too busy to come to the phone.

As the economic stagnation persisted, the obligatory bond between salaryman and company—the sacred relationship that had replaced the feudal tie between samurai and lord—began to erode. If companies could discard loyal employees for financial reasons, then what did the masculine ideal built around corporate devotion mean?

As salarymen lost faith in the companies, the companies responded by abandoning the social contract that had defined post-war Japan. They stopped hiring full-time employees with lifetime job security, and instead relied on temporary workers without benefits or long-term prospects. For the first time since the 1950s, college graduates couldn't find stable employment—a crisis that persisted well into the new millennium. Then in the late 1990s and 2000s, neoliberal economic reforms justified these changes and cemented them as permanent features of Japanese capitalism.

An entire generation of men raised on their fathers’ real-world success stories were suddenly thrown into socioeconomic uncertainty. The “job for life” that had been achievable by the everyman, if he just stayed loyal and worked hard enough, could no longer be counted on.

The old collective solidarity that had powered the miracle economy gave way to a new flavor of individualism: Every man for himself.

Discontent and Japanese Masculinity

Though some still managed to succeed on the traditional pathway to salaryman status, a massive segment of the male population was left eking out a precarious living by bouncing between part-time jobs without security, benefits, or most importantly, social respect. Hence, the “permanent part-timer” (furita) was born.

Now, in America, with our individualist masculinity, personal fulfillment through creative pursuits can justify economic precarity. As long as a guy has a cool hobby, he can pretty much work part-time his whole life and nobody thinks too much of it. We say something like, “Sure, he works at the gas station, but he’s really into his music.”

But for collectivistic Japanese masculinity, hobbies can't substitute for institutional belonging. Employment is perhaps the most crucial of a man’s obligatory relations, tied tightly to his identity. Part-timers don’t just earn less, they are excluded from building the long-term, reciprocal “trust relationships” (shinrai-kankei) with a company that demonstrate social recognition of full manhood. Even worse, it’s the kind of thing your relatives typically won’t let you hear the end of: Practically no one celebrates a man’s artistic pursuits if he can't fulfill his primary social obligations.

As the link between lifetime employment and masculine identity broke down, many of this “Lost Generation,” whether in their own eyes or those of others, were left unable to become men.

Withdrawal Syndromes and the 8050 Problem

Faced with impossible standards and limited opportunities, different segments of the male population developed different coping strategies—most involving some form of withdrawal from social expectations.

Some simply chose not to even try to “be a man” in the traditional, collectivist sense. Instead, they disappeared, a practice called johatsu.

A few became creative “hobby guys,” whose joyous rejection of social norms would be well-accepted in a personal freedom-loving country like America. Not in Japan, though, where abdication of adult responsibility is regarded as prolonged adolescence.

A larger group became NEETs: “Not in Education, Employment, or Training.” They don’t subject themselves to the indignity of working part-time jobs, or even seek them out. As to how they spend their time, your guess is as good as mine.

NEETs blend into another more extreme group that emerged in the post-Bubble era: the hikkikomori, the shut-ins. These men have withdrawn so completely from social participation that they rarely leave their homes, sometimes for years at a time.

I find it curious that the concept is fairly well-known in the West. As its rise corresponds with personal computing and the extremely-online otaku culture now popular worldwide, I wonder if the hikikomori hasn’t been romanticized as a kind of modern-day recluse; a figure of spartan minimalism amidst a chaotic world.

From what I have seen and heard, however, it’s a serious psychosocial pathology that manifests as a form of parasitism. No hikkikomori lives entirely alone. There is almost always someone in the background, usually an aging mother, feeding and ultimately enabling their lifestyle.

The fallout of all this resulted in what is called the “8050 problem” today: Men in their 50s still dependent on parents in their 80s. The elderly parents require care, but their dependent sons not only can’t afford it—they lack even the basic skills needed to interface with medical systems, insurance bureaucracies, and funeral homes.

It’s been said that Japan has entered the “Age of 1,000,000 Recluses,” but this is probably an undercount. To be sure, a significant percentage of adult men are essentially opting out of social and economic participation, but to varying degrees. Even in national surveys, what we might call “reclusivity” is increasingly understood as a spectrum disorder, measured by questions like, “Can you walk to the convenience store alone?”

With the statistics showing annual increases in all types of recluses, media outlets are already talking about the looming “9060 problem.”

Fertility Gap, or Fertility Trap

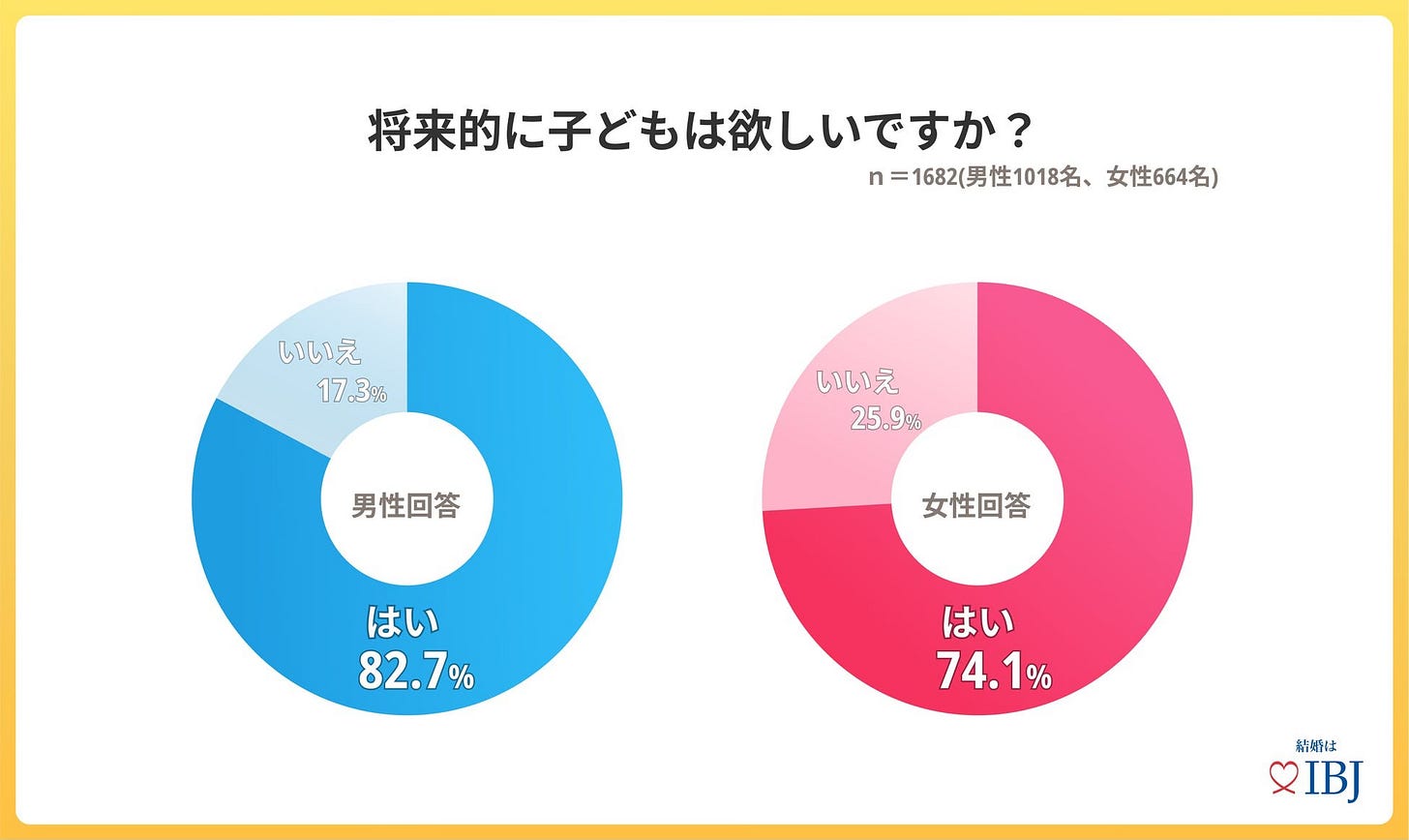

This brings us to the cruel irony at the heart of Japan's demographic crisis. When surveyed about their desires, a 2021 national survey found 81.4% of men “intend to get married someday,” and other surveys show majorities of young Japanese men express interest in having children—sometimes at higher rates than their female counterparts. The problem, then, isn't lack of desire for family formation.

The problem is perceived capacity for it. This comes into view if we shift from “Do you want children?” (individual desire) to “Can you have children?” (collectivist obligation). That is, "Can you uphold all the complex relationships and obligations that children entail?"

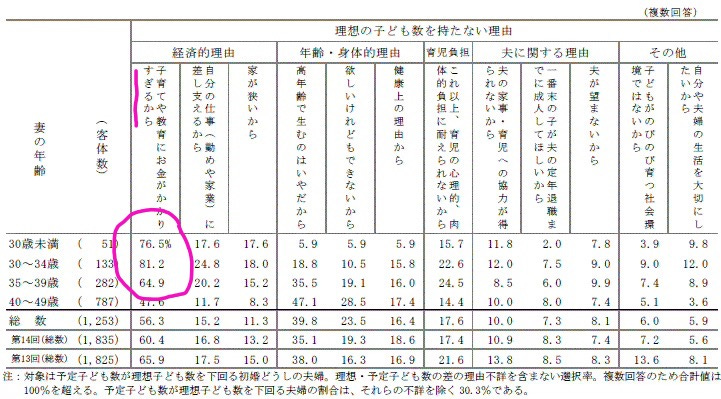

Can you secure stable, well-paying employment that signals your reliability as a provider? Can you afford to support a wife who will be expected—sometimes by law and almost certainly by social pressure—to leave her career after marriage/childbirth? Can you pay for the private tutoring and cram schools that every middle-class child needs to navigate Japan's intensely competitive educational system?

In other words: Can you be the kind of man who can have kids?

No survey asks all these questions, but judging from the birthrate, a growing segment of Japanese males are answering, “I don’t think so.” Having children remains anchored at the top of the hierarchy of relationships that define collectivist masculinity, but the economic foundation for that identity has been systematically eroded.

This creates a psychological trap with no clear escape. Young men find themselves caught between two incompatible systems: an increasingly individualistic economy that has destroyed traditional employment security, and collectivist family expectations that still demand fulfillment of the old masculine ideal.

Unless childbearing somehow becomes a decision that can be made on the basis of individualistic personal fulfillment rather than collectivist obligation and social duty, birthrates will probably continue falling. Should individualism penetrate that deeply into Japanese society, however, other unintended consequences are likely to emerge.

Geriatric Godzilla: Coming to a Country Near You

Japan's demographic crisis offers a preview of coming attractions for the entire developed world. Birthrates are declining precipitously across advanced economies as variations of the same dynamic play out in different cultural contexts. South Korea now holds the record for the world's lowest fertility rate. European nations struggle with aging populations and inadequate replacement rates. Even China, despite abandoning its one-child policy, faces looming demographic decline.

A so-called "Silver Tsunami" of aging populations will sweep across the modern world over the coming decades; Japan simply happens to be at the gnarly edge of it. And though Japanese culture may appear idiosyncratic to Western observers, the underlying forces—economic instability undermining traditional masculine roles and family formation—are universal features of post-industrial society.

In my last post, I said depopulation represents a Don't Look Up! moment for Japan. But the shadow of demographic crisis is looming over the entire globe. Unlike the comet in that film, however, this isn't hurtling toward us from outer space. It’s emerging from our own choices; from our collective inability to reconcile modern economic systems with ancient human needs for purpose, identity, and family.

The Japanese case is unique in its details, and aging developed nations are likely to differ in how they experience their respective demographic crises. The common challenge all will face is whether they can prove more capable than Japan in adapting their cultures to support family formation under post-industrial economic conditions, or succumb to Geriatric Godzilla.

Geriatric Godzilla is coming to a country near you. Will you be ready, or just keep scrolling?

I’m in a situation similar to the hikikkomori myself, so I have enough time on my hands to make some offbeat observations: the whole piece is a neat companion to John Ganz’ recent piece about the American fascination with Japanese industry and craftsmanship in the 1980s.

Also, the whole theme of the balance between individualism and social obligations was somehow in tune with stuff I’ve read lately: a lecture contrasting America’s constitution (emphasizing liberty) with Germany’s basic law (dignity); Abraham Lincoln’s invocation of individual self-sacrifice in service of the nation in the Gettysburg Address (a very American parallel to Japanese masculinity, no?); Martin Luther King’s address comparing communism and capitalism and what each forgets…