Because we live in the most ridiculous timeline, Elon Musk wants to deorbit the International Space Station (ISS) because an astronaut hurt his feelings. It all started when Musk appeared on John Hannity the night of Tuesday, February 18th. Hannity asked Musk about the two astronauts, Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, who were stuck on the ISS for nine months. The astronauts lost their ride when the Boeing Starliner they rode up on was deemed unsafe for their return trip due to thruster malfunctions. They will be riding back on a SpaceX Dragon capsule later this month.

Musk's response was that the astronauts were stranded for political reasons. He claimed that Biden actively prevented their return until after the election because he didn’t want to make SpaceX, and by extension Musk, look good out of retaliation for Musk’s support of Trump. Musk’s claim is demonstrably false. NASA has many contingency plans every time it launches astronauts, and one of them is for the event that astronauts cannot return in the capsule they arrived in. The two astronauts would be added to ISS expedition 72. Only 2 astronauts flew up with the SpaceX Crew-9 mission in September of last year so that they could take the stuck astronauts back with them, originally scheduled for February this year. It is NASA’s policy that expeditions overlap so that the previous crew can train the incoming crew. So when the SpaceX Crew-10 mission was delayed due to manufacturing delays on the part of SpaceX, the return of the astronauts on the Crew-9 mission was also delayed. The only difference between the Biden and Trump administrations is that the Trump administration approved the use of a flight-proven refurbished Dragon capsule, which will push the whole process forward by a few weeks.

In response to a clip of the show posted on twitter, ESA astronaut and Expedition 70 commander Andreas Mogensen retweeted “What a lie. And from someone who complains about lack of honesty from the mainstream media.” Musk’s mature and even-handed response was to call Mogensen “fully retarded,” going on a diatribe against the astronaut. Six minutes after which he tweeted, “It is time to begin preparations for deorbiting the space station. It has served its purpose. There is very little incremental utility. Let’s go to Mars.”

I would love to outright dismiss Musk because his claims are, in fact, wrong, divisive, undermine political cooperation, and are, quite frankly, childish. But he also happens to be extremely powerful, especially when it comes to space policy. So let's take his final statement, about deorbiting the ISS, seriously and actually ask: should we?

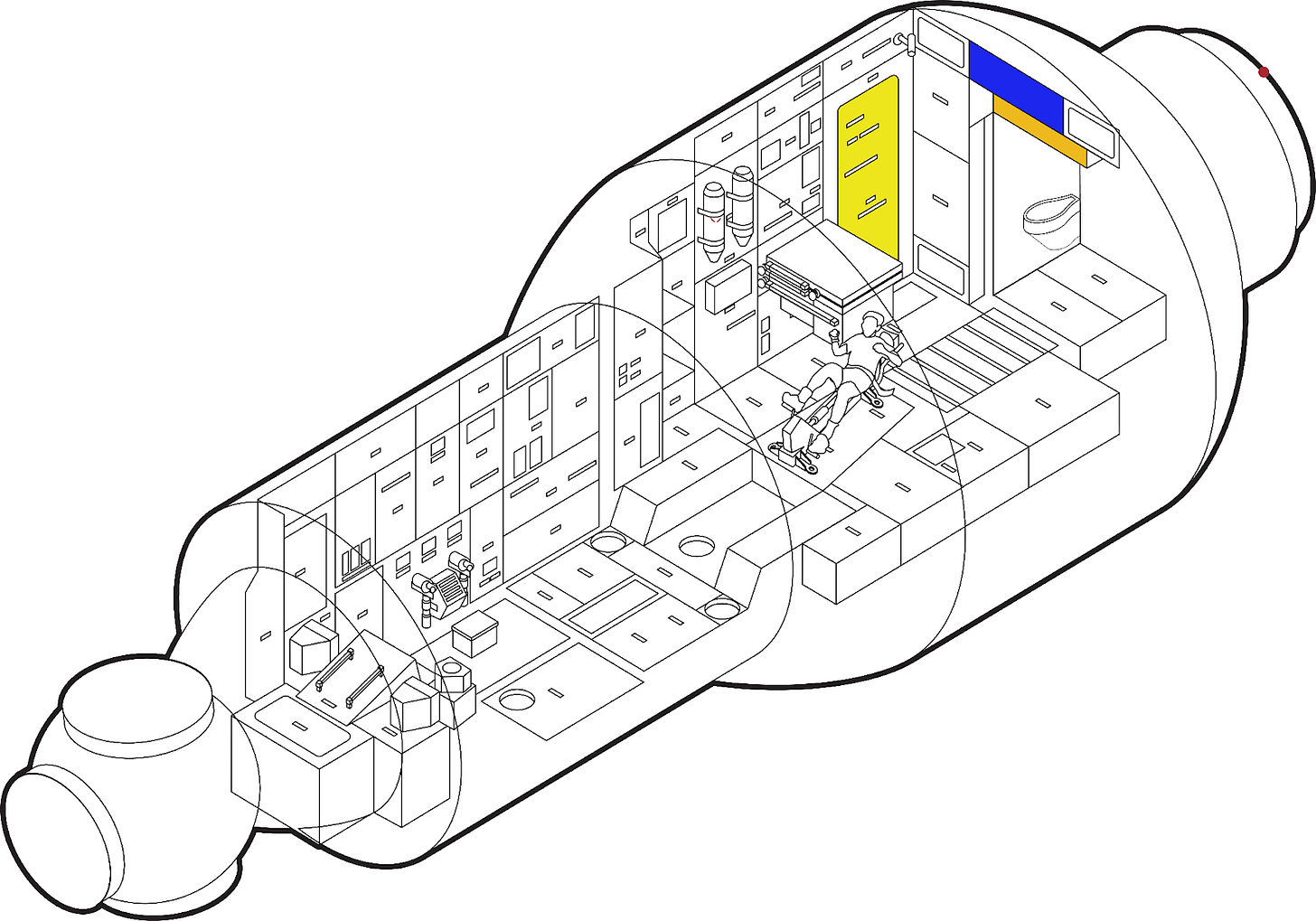

NASA is already planning to deorbit the ISS. In 2031, NASA will use a modified SpaceX Dragon capsule attached to the ISS to accelerate and control its descent into the atmosphere where most of the station will burn up. The rest will land harmlessly in the ocean. In fact, when construction of the ISS first began in 1998, the plan was to finish by the year 2000, operate the station for 15 years, and deorbit it in 2015. Partly due to delays in construction, which wasn’t really finished until 2011, and partly due to better than expected scientific performance, NASA and their international partners extended the lifespan of the ISS several times. But the station was never meant to last forever, and deorbiting was always the station’s inevitable end.

Why We Should Deorbit the ISS

Now it is reaching the point where further extensions on the station’s operational life are less and less appealing. First, as the station ages and its parts and pieces start to fail, they in turn lead to several severe safety concerns. For example, the Zvezda module, a module on the Russian portion of the station where Russian cargo module’s dock to the ISS, now has a severe oxygen leak of about 1.8kg/day. The specific source of the leak is unknown, but it is almost certainly due to microscopic structural crack from everyday wear and tear. The leak has gotten so bad that it poses the potential for catastrophic depressurization. The hatch for Zvezda is kept closed unless the module is in active use, in which case the hatch between the Russian section and the rest of the ISS is kept close to prevent the total destruction of the ISS in case of failure.

But it gets worse, just last year, a pump broke in the process that converts urine back into drinkable water. The ISS relies on recycling to provide enough water for the crew to survive, so while the pump was broken they were forced to store the urine. But storage is limited, and the the ISS quickly ran out of space, forcing NASA to take extra clothes off of the flight manifest for two astronauts in order to get the replacement part up quickly enough.

On top of that, both the Russian and American space suits are starting to fail. The water that cools the American space suits has on several occasions leaked into the suit’s helmet. On one occasion it nearly drowned ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano. The Russian suits, using a different design, don’t have that problem. But they do have potentially deadly problems with decompression, which has caused them to be taken in and out of service.

Aging parts also increase the difficulty and expense of upkeep for the ISS. Space is a harsh environment, and that environment is slowly degrading the structure of the station itself. In this sense, the lifespan of the ISS is inherently limited. The coatings designed to maintain a consistent temperature despite dramatic differences between sunlight and darkness (because of the lack of atmosphere) are also starting to erode away with noticeable performance degradation. On top of which, docking puts a small strain on the docking structures of the ISS, limiting the total number of times a capsule can dock to each port. Over time the ISS’s solar panels have also degraded at the same time as power requirements have increased. NASA has delivered new solar panels, which roll up like a carpet, but combined with other wear and tear, the ISS is just plain reaching the end of its life.

ISS maneuvering systems are also being put under substantial strain. Despite being 250 miles above the surface of the Earth, there is still just enough atmosphere to produce drag on the space station. This drag slowly slows its orbit, so without onboard thrust to correct its orbit, the ISS would eventually fall back to Earth on its own. But these thrusters have other work to do. The increasing prevalence of orbital debris, the ISS has had to do a total of 39 debris avoidance maneuvers. This culminated in what was described as a “spacecraft emergency” in 2021 when a Russian research module inadvertently fired its thrusters. The ISS completely lost its ability to control its orientation and was spinning the station, the size of a football field, around. The thrusters were eventually shut off, and the station returned to its correct orientation. But clearly the systems on the ISS cannot function correctly forever.

But there are other concerns that might lead us to decide to deorbit the ISS even if these issues were not so pressing. First, as NASA priorities change, they will need different projects to support those priorities. NASA does have a successor to the ISS planned. It is called the Lunar Gateway. Gateway is part of NASA’s Artemis program to send astronauts to the Moon. Like the ISS, it is a space station built collaboratively by the US and their international partners (sans Russia). Unlike the ISS, it is a much smaller station, with the much narrower focus of supporting human missions further afield from Lunar orbit. A station in Lunar orbit will be more useful to NASA’s future mission goals than one in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). And it isn’t likely that NASA will have the funds to operate both, especially as operating the ISS becomes increasingly expensive.

In general, resources are limited, and choosing to keep operating the ISS isn’t just a choice in favor of the ISS, it is a choice against any of the alternatives that we might pursue with those resources. Following the pattern of commercialization started with their Commercial Orbital Transportation Program (COTS), NASA intends to follow up the ISS’s legacy in LEO with a multitude of commercial offerings. Similar to their commercial crew and cargo programs (C3PO), NASA is providing funding to four groups to develop commercial destinations in LEO through a program by the same name. NASA contributes to their development, and then NASA will pay to use them. If it works like the C3PO, NASA will save money compared to operating their own station while at the same time seed an industry that might have unexpected benefits. But all of that is unlikely if NASA continues to pour resources into prolonging the life of the ISS.

Why Not to Expedite Deorbiting the ISS

But Musk wasn’t just acknowledging the need to eventually deorbit the ISS. Nor was he defending NASA’s timeline for deorbit. He wants to start the process now. And while there are many good reasons why NASA is going to deorbit the ISS, there are just as many reasons why they are doing it in 2031 rather than right now.

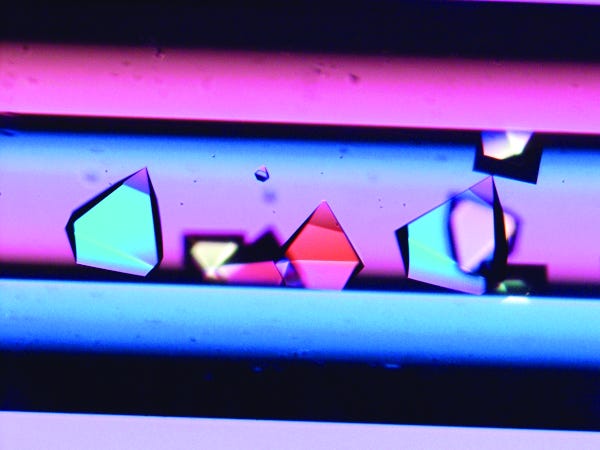

First, the ISS has done, and continues to do, a lot of really important scientific research. The ISS has been the site for breakthroughs in fields like medicine, particle physics, and material science. The microgravity environment on the ISS enables unique ways to manipulate proteins, which are the basic structures of DNA, viruses, and microbes. The improvements in our fundamental understanding of these structures contributes to new medical treatments for ailments like cancer and Alzheimer’s. Studying bone and muscle degeneration of astronauts in microgravity has also led to new treatments for those same conditions on Earth. Positioned outside the Earth’s protective atmosphere, many more cosmic particles pass through the ISS than the Earth’s surface. Studying the particles that pass through the ISS has improved our understanding of cosmic phenomena like quasars and black holes. The environment of the ISS is totally unique compared to anything on Earth, and much of the research done there can *only* be done there. At least for now. If NASA deorbits the ISS before they can plan or launch an alternative, we simply lose out on the ability to do this kind of research.

As much as Musk wants to rush to Mars, the experience NASA and their partners have gained from operating the ISS is invaluable to conducting deep space missions in a safe and responsible way. Trips to Mars or other deep space destinations will take a long time. The ISS has been a very important tool for understanding what it takes to succeed for extended stays in space. It would be horrible to send astronauts to Mars, or even worse, civilians, only to realize after potentially dozens of trips that there are long term health problems we could have mitigated against. Furthermore, learning things like what kinds of long term wear and tear habitats experience, or what kinds of power or atmospheric errors we can expect that might otherwise have been unpredictable are irreplaceable experiences for preventing future deep space disasters. ISS is an exceptional platform for learning how to go to Mars more safely.

The ISS has also been an important tool for engendering international cooperation. Fifteen (15) different countries currently support the ISS, including Russia. This collaboration has been especially important to regulate the US’s and EU’s sometimes contentious relationship with Russia. Even during the invasion of Crimia and the more recent invasion of Ukraine, through sanctions against Russia, the collaboration on the ISS has remained. Russia has threatened to stop sending astronauts to the ISS and even to crash the ISS, but have never actually acted on these threats. Cosmonauts and astronauts still work together in space even when their leaders can’t do the same on Earth. This international collaboration and cooperation is an extremely important diplomatic benefit of the ISS.

Sadly, when the ISS is gone, that benefit will disappear. The Gateway station, and the Artemis program it is a part of, are still a multinational endeavour, but in a much more limited way. The Artemis accords include only US allies and Russia is noticeably absent. Even then, the European signers of the accords have complained that the program is too US centric. And the reality of actually building the Gateway station is tenuous. In many ways it has fallen prey to the iron triangle, where congress members, NASA, and contractors all benefit from drawing out the project without ever finishing it. Like the Constellation program before it, Artemis seems poised to continue to pay contractors and support jobs in key congressional districts with no end in sight. I am not holding out hope that even the minimal cooperative benefit from the Gateway station will materialize before the ISS is deorbited in 2031, much less if NASA deorbits it sooner.

But just because deorbiting the ISS will reduce the opportunities for nations to collaborate with the US in space, doesn’t mean international collaboration will cease. Instead, it presents a notable possibility that China will become more collaborative. Right now, when the ISS burns up in the atmosphere, the only space station remaining will be China’s Tiangong. In the past China has had a very insular space program, but now it is well established and the government has proven its technological and financial capabilities. The Chinese government now seeks to increase their influence over space policy through international cooperation. They have announced a willingness to host non-Chinese crews on the Tiangong, been training their taikonauts with ESA astronauts for potential future joint missions, and included international research projects in the station’s first approved set of experiments.

China’s potential orbital preeminence post-ISS isn’t without benefit. Collaboration may prove a regulating force for China in much the same way it has with Russia. It may force their government to conform to norms surrounding important space related issues, such as deorbiting space assets, space junk, and anti-satellite missiles. It may also provide some leverage in the case of future conflicts, for example around Taiwan or in the South China Sea.

On the other hand, it will certainly give China a substantial increase in their influence over international space norms. The possibility remains that, instead of getting China to behave better, they might use that influence to undermine existing norms. I, for one, don’t want dropping used rockets on other countries and creating thousands of pieces of space debris through normalized testing of anti-satellite missiles to become normal activities.

And certainly in this scenario an increase in Chinese influence comes at the expense of US influence. The most frustrating aspect of this loss of influence is that it doesn’t have to be. China’s eagerness to increase their international cooperation in space could be an ideal opportunity for the US to pursue the same strategy they did with Russia: collaborate on the next space station with China. China gets to participate in setting norms and policies for space development, and the US gets to play a more active role in regulating China’s threats to US interests. But congress has made this sort of collaboration illegal. Certainly it would not be without risks, but those risks are manageable, especially in the context of specific and limited space based collaborations.

Collaborations between nations aren’t the only ones the ISS engenders. NASA has used, and plans to continue to use, the ISS to help commercial companies prepare to manage their own private space stations. In 2016 NASA attached the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) to the ISS to support the development of private space station modules by private company Bigelow Aerospace. NASA plans to do the same with Axiom Space. NASA is paying Axiom to attach two (2) modules to the ISS: a power module, and a habitat module. The first module is scheduled to go up in 2027. After they test these two modules, they will decouple from the ISS when it is deorbited, and Axiom will attach three (3) more modules: an airlock module, another habitat module, and a research module. They will then have a fully functioning private space station. But this plan absolutely relies on the ISS being in orbit until 2030, as currently planned. While deorbiting the ISS eventually is necessary for the takeoff of any future commercial stations, doing so too soon will likely quash this goal. The industry currently cannot operate without support from NASA, much like the private launch industry.

The Underlying Issue: Who Decides?

But the important difference between the ISS and commercial space stations, no matter how successful, is that regular citizens have no control over commercial stations. That isn’t to say that we had much control over the ISS per se. I don’t have any say over what kinds of experiments to prioritize. Chances are you never got any input over collaborations with international partners. Although we did get to vote on the name for the exercise module, even if NASA didn’t choose the actual winning name. But there is an implicit understanding that the officials at NASA are making these decisions with “the public interest” at heart, no matter how fraught that concept is academically. Moreover, NASA officials do have public accountability. They have to be open about their policies and activities. And elected officials, from Congress or even the President, can intervene if they don’t like the decisions of NASA officials. Plus, NASA has independent management and technical oversight from their Office of the Chief Engineer (OCE), and external oversight from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). So even if we don’t get to represent our interests directly, there are still a variety of mechanisms to ensure that the various interests of the public are actively considered in decision making. One cannot say the same about commercial space stations.

Commercialization in general removes public interests from decision making. Consider Elon Musk and SpaceX. Musk is most certainly a national security threat now, given his access to sensitive information about nearly every American and his many conflicts of interest, including ties to Russia and China. But this isn’t new. For years prior to his post at DOGE, Musk continued to get hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts with the US government, even when his positions and actions actively undermined stated US policy positions or threatened national security. The services SpaceX provides NASA and the DoD, services mostly paid for through Space Act Agreements (SAAs), are just too important and irreplaceable. But because SpaceX is privately controlled by Musk, the US government has no real means to act when Musk goes off the rails. He is far less accountable and more capable of influence than any federal bureaucrat.

The future beyond the ISS looks much like what I’ve just described. If we’re lucky, we get many smaller privately operated space stations that can allow cheap and easy access to LEO for more research, orbital assembly of deep space vehicles, or even space manufacturing. But in exchange we give up control, and even any semblance of accountability, for the policies and decisions those companies pursue. All the while SpaceX, and thus Musk, continues to dominate NASA’s push for exploration to the Moon and Mars.

For me, this is the tension that underlies Musk’s infantile outburst, and the very work he is doing at DOGE: who decides? We are left with an unappealing choice between technocratic bureaucracy and a plutocratic oligarchy. It’s experts vs. billionaires. We have written a lot, and I mean *a lot*, about how technocracy undermines democracy here at Taming Complexity. (Really, do a quick search of our articles, the problems with technocracy is something of an obsession of ours). But our preference for more democratic participation in steering the direction of technological development and our government just isn’t on the table right now. Right now we are being asked to choose between governance dominated by bureaucrats and governance dominated by unaccountable corporate business owners constantly striving to shut out any competition to their exercise of power. If that is the choice I have in front of me, I know which I will pick every time.

I don’t disagree w/ Musk per se. The ISS was always going to be temporary. It was never going to be around forever, and shouldn’t be, even if it's still doing good science! So I’m neutral about deorbiting and decommissioning the ISS as a sole issue in a vacuum (pun intended). But it clearly matters what comes next. What Musk is proposing, or has proposed or supported in the past, has a lot of flaws. It's clearly self-serving, even though taking astronauts to the ISS is a big part of SpaceX’s business right now. It's a sacrifice he’s willing to make in order to have more control over American space policy and the direction of space development. But do we want to give up that control? Is that control better in the hands of Musk, or better in the hands of public officials? Frankly it would be better with a lot more public accountability, rather than being predominantly technocratic. But even the choice of oligarchy vs technocracy is an easy one in my book. At least public officials have *some* levers for accountability. Musk has none. And considering that the ISS is still doing good, useful work, I don’t see any reason why we should rush to decommission it until we have an actual reasonable vision or policy for how to follow it up.