Planetary Prophecies

Why revelatory science will never let us do environmental politics on "easy mode"

“Atlantic Ocean circulation nearing ‘devastating’ tipping point, study finds…adaptation would be impossible.” So reads a recent headline from The Guardian. Depending on your own politics, this either sounds like yet another cataclysmic warning from science going unheeded or a questionable model being overhyped for clicks. Roger Hallam, the co-founder of Extinction Rebellion, calls the prediction “just the beginning,” that “we are looking at billions of deaths.” On the other hand, executive director of Project Drawdown, Johnathon Foley, describes the study as “a pretty unrealistic computer simulation.” Reponses from climate skeptics are, of course, even more dismissive.

I’m not that old, but I’ve still seen the exact same discourse play out enough times to wonder why we keep doing this. How long are we going to fight the same unproductive political battle, debating whether a new piece of research justifies immediate and radical social changes? The trouble is, I think, that some environmentalists insist on turning science into a source of revelatory inspiration, to make it not just a prediction but also a prophecy. And it may be impossible to square the prophetic with democracy.

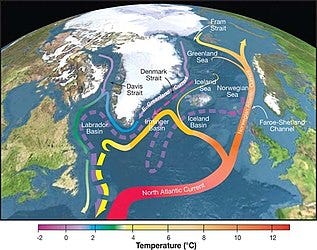

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is an ocean current that, to perhaps oversimplify things, ensures that Europe is relatively warm compared to other places at similar latitudes (i.e., North Canada and Siberia).1 The AMOC hasn’t been as weak as it is now in a long while, and this latest study modeled how melting ice from Greenland could shut the current by flooding it with too much freshwater. That is, they drove the model until the AMOC flipped from its current state to something that would disrupt global climate patterns [i]. They then fit the model to data from the Southern Atlantic in order to extract an “early warning signal,” predicting that the tipping point could happen between 2025 and 2095 (the 95% confidence interval).

I’m in no position to judge the research one way or another. I used to be a mathematician, but this isn’t an area that I’m familiar with. That said, during my math training, the message “Don’t confuse the model with reality” was beat into my brain. Consequently, I take all models with a grain of salt, especially when they deal with nonlinear behavior, such as tipping points. Models of complex phenomena are sensitive to the starting points and parameters that you feed into them, and sometimes the predicted behavior has more to do with how the model was designed than with the data being fit into it, especially once you start extrapolating into the future.

In any case, the issue at hand isn’t really with the model itself but how to interpret it. Whether it merely merits more research and renewing our commitment to accelerate climate-friendly technological changes or instead calls for “transformative” social change isn’t actually obvious. Or, better stated, the mathematics itself can’t tell us what the model should mean to us.

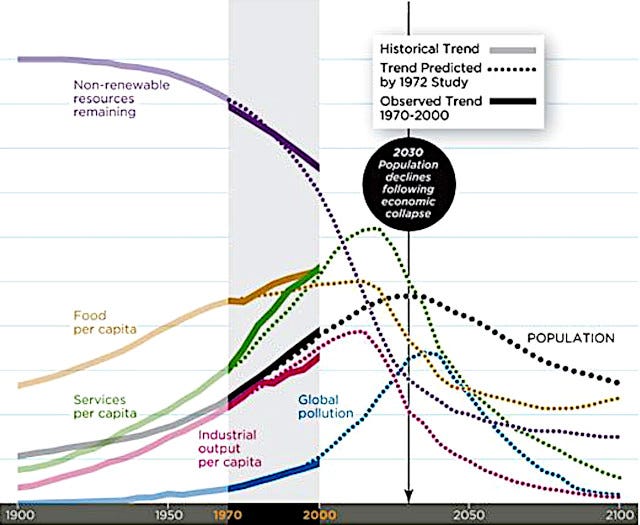

We’ve been here before. In 1972, worries of catastrophic environmental collapse were rooted in another large-scale model. A team led by Donella and Donald Meadows presented The Limits to Growth, one of the first global systems dynamics models. It’s, of course, not the same as quantitatively representing the AMOC. It actually attempts something far more ambitious: modeling the world system undergirding human civilization.

The Meadows’ model (which iterated upon the pioneering work of Jay Forester) reduced this world system to five core variables: population, food production, pollution, resources, and industrial production. And it was built on real-life data. Nevertheless, the very character of the model required them to create indexes or proxies for these awesomely diverse aspects of reality and make assumptions about their interactions. How much would technological change reduce pollution? How exactly would population increase put pressure on chromium deposits and arable land? The gist of the model: Growth-based societies are headed for collapse.

Criticism from economists such as William Nordhaus questioned the empirical basis for the Limits to Growth model. Did it really agree with current data? To them, the model was just a repeat of the dismal predictions of Thomas Malthus. The systems modelers, on other hand, believed the economists didn’t really understand what they were doing, and even came to Malthus’ defense.

The scientific debate between these two groups is interesting, but many of the disputes are beside the point. The core assumption of the model is the existence of clear finite limits to all of the variables in the world system. Moreover, it presumes that there is a lack of sufficient negative market feedback about crises in the making, like resource scarcity, which invariably leads to overshoot and collapse. Inherent to the model are beliefs about how both the Earth and human societies work and how we collectively respond to impending problems.

The trouble is that disagreement over environmental tipping points largely hinges on the validity of these very assumptions. Today’s ecomodernists, for instance, believe that we can decouple economic growth from increasing energy, CO2 and other vital resources. Technological substitutes may arrive just in time to mitigate the harms of running out of what used to be vital and irreplaceable resources. [ii] And they view consumption itself as somewhat self-limiting. Cars can only get so big, and people can only eat so much food. And economic is actually stagnating in many developed nations. Such changes don’t eliminate limits to growth, but set them far enough out of the way that the eventual peaking and decline of the world’s population provides us with a soft landing.

But, like I said above, such models aren’t just predictions but also prophecies. A key part of all apocalyptic prophecies is that they are meant to unveil the inherent corruption of the current society. Just as Christian Millennialists anticipate God’s judgement eventually raining down on nonbelievers, eco-apocalyptic visions make nearly all of us into environmental sinners. The difference is that environmental revelations are meant to be “self-defeating prophecies.” Should we repent and change our ways, we can find ecological redemption, albeit on Earth rather than in Heaven.

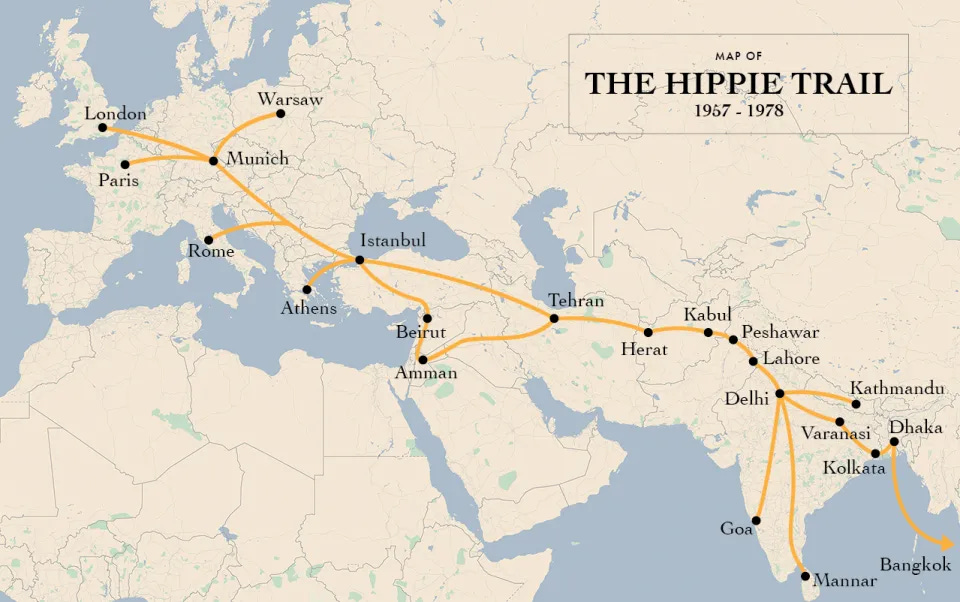

Limits to Growth was as much prophetic as predictive. The Meadows’ weren’t just talented scientists chasing their interests. Inspiration for their model also came from their experiences on the “Hippie Trail,” an overland route from Europe to India. That trip exposed to both unimaginable poverty, seemingly unsolvable by modern science and technology. And they returned to the US aghast at the material corruption of their friends and family, no longer understanding why they “needed so much stuff,” especially when increased consumption didn’t appear to make them any happier (Or, more likely, didn’t stop them from complaining about everything).

Donella Meadows extoled life in a proposed “equilibrium society” as not a “sacrifice” but as enabling a higher kind of freedom, one based on pursuing “more fulfilling activities.” Limits to Growth was clearly not simply a sober look at the data, but also a reflection of the Meadows’ own deeply held moral convictions. It was meant to unveil the corruption of growth-based societies, a moral degradation that not only ostensibly makes us unhappy but will also lead to ecological ruin.

I’m not sure yet if prophetic thinking is a problem in itself. Or, I wonder if it might be a largely unavoidable complication when we try to make sense of warning signals from environmental science. Good luck finding someone without strong moral convictions about how people should dwell on the Earth. And, even so, would we even want someone without them to be in charge of interpreting the data for high-stakes global challenges?

The real issue is that we tend to forget that these convictions are at work in the background. For instance, a recent podcast documentary on The Limits to Growth model basically blames the failure of governments “to begin a controlled, orderly transition from growth to global equilibrium” on ideologically biased economists criticizing the model too much. The podcast even frames these events as a “True Crime Story,” ostensibly making economists into villains orchestrating a transgression against the planet.

Revelatory science invariably splits the world into good and evil, between heroes trying to save humanity and corrupt denialists. But science-based prophesizing ends up being even more insidious than religious millennialism. The emphasis on research data can lead advocates and critics alike to believe that they’re just “following the science.” They forget the moral certainties in the background, which invariably arrive just in time to paper over any inconvenient factual uncertainties. They risk putting Science in the place of God, asking us to receive experts as prophetic messengers who can guide us through the coming crisis.

We desperately want do politics on easy mode. We want an undeniable truth about the environment to create a moral consensus.

We need to recognize this pattern at work when we talk about the AMOC and other tipping point models. No model can be fed with enough data to predict the future with total certitude. It can only alert us potential hazards. The question regarding how to handle hazards takes us into non-scientific territory, obvious when we reflect on the fact that some people willingly skydive while others can’t bear to board a plane. Some people still mask up in public, while other people are happy to take in the atmosphere (including the respiratory particles) at indoor concert venues. Whether a person responds to the AMOC tipping point model with horror or skepticism depends on which underlying prophetic story is part of their broader worldview. Do they see modern industrial society as ecologically corrupt or as naturally leading to a Good Anthropocene?

We can’t begin to hammer out feasible compromises to avert the worst hazards, while retaining some of what many of us value in life, so long as uncertain environmental science keeps getting turned into a revelation. It locks us into debating the truthfulness of competing prophecies, but in seeming obliviousness to the moral ideas at their foundation. We are, therefore, not at all prepared for making collective decisions within the constraints erected by our often irresolvable disagreements.

That’s probably easier said than done. We desperately want do politics on easy mode. It’s understandable to want to seek out an undeniable environmental truth. It promises the possibility of worldwide moral consensus. It offers to make our moment on Earth especially historically meaningful. We can be heroes, rising up to manifest ecological redemption in the face of environmental crisis. Then difficult policy choices could become mere technical decisions, something informed by models and predictions rather than forged via imperfect and sometimes incoherent political compromises.

If I’m right, however, a reliance on planetary prophecies actually makes political progress for environmental issues only more difficult to achieve. What are meant to be self-defeating prophecies actually become self-fulfilling ones.

But I’m at a loss. We haven’t seemed to have learned that lesson in the 52 years since The Limits to Growth. What has stopped us? And how can we learn it now?

[i] Questions about the model’s applicability to our world largely stem from how hard they needed to push the model to arrive at a tipping point. It took thousands of model years and more freshwater than would ever run off of Greenland’s glaciers.

[ii] It’s notable that the Limits to Growth Model presumes a finite reservoir of Natural Resources, defined irrespective of our ability to discover or make us of them, an assumption that probably lends itself to a more conservative view of resource limits

Correction 3/3/24. My phrasing, in hindsight, grossly oversimplifies the situation. The gulf stream does far more to warm the Northern Atlantic than the AMOC. The potential collapse of the AMOC would likely create a “cold blob” in that part of the ocean, while leaving the rest of the gulf stream unaffected.