Better Together

What Israeli housing policy has to teach us about overcoming political stalemate

Most of us aren’t represented in a good many of the decisions that affect us. As Michael showed in his last post, the NIMBYist response to urban densification is democratically deficient because local meetings can’t effectively include a key group: The people who want to live there, but can’t afford to. Albuquerque city council decisions can’t take into account the views of New Mexicans who are forced to live outside of the city because of rising rents. A neighborhood association can’t survey the opinions of people who could be neighbors, but only if relaxed zoning rules allowed for duplexes, or even low-rise apartments. For a lot of decisions, *we* invariably decide for others.

While I’ve long been a staunch “small d” democrat, and consequently skeptical of the burgeoning power of political executives, bureaucrats, and big business, I increasingly have an appreciation of how public officials and policy analysts could compensate for the limits of voting. Especially in polarized systems, for electorates who think more in terms of partisan identity than about exactly why issues divide them, politicians often only represent a minority of their theoretical constituents. Insofar as NIMBYism is not really what democracy looks like but rather reflects of a failure to do democracy well, we clearly need new ideas regarding how to do urban politics.

There’s a lot of potential for improved democratic leadership. But it requires that public officials and activists see the world with different eyes. Rather than believing that they can know or implement the “public good,” which is really unknowable. They ought to strive to be experts in learning to understand and partially reconcile public disagreements.

Turing Political Losers into Winners

It is 1999 and Israelis have a problem. No, not that one. I mean housing. The small country had experienced decades of explosive immigration-fueled population growth. Vast neighborhoods of shoddy apartment buildings had been built over the years to house these multitudes, but the government has begun to worry that they had future disaster in the making. An earthquake in Turkey that year killed thousands, and a similar event in the Levant would wreak havoc. Moreover, like elsewhere in the developed world, housing costs were steadily rising.

Similar to the United States, urban redevelopment in Israel was a dirty word. NIMBYs seem to be a problem everywhere. But as a pair of political scientists have pointed out, the reason for this is quite simple: a conflict of completing interests. Developers are happy to build more and denser housing. They represent the interests of potential residents, who stand to gain. But current residents often only stand to lose, and redevelopment doesn’t usually compensate them for their losses, whether it is increased traffic, difficulty finding parking, or a less tangible change in neighborhood quality. While potential residents are only indirectly represented in the democratic process, a very vocal minority of local residents tends to exercise veto power over new proposals.

Yet Israel has been able to deftly work through the NIMBY problem. Today 50 percent of new housing units coming online are the result of demolition and densification in existing neighborhoods. How?

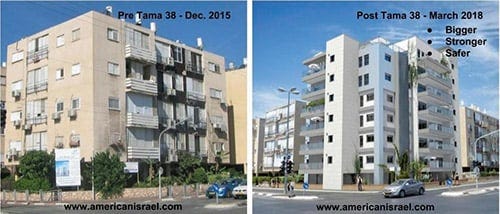

Israeli geographer Tal Alster breaks the story down in an article in the magazine Works in Progress. Two programs were implemented roughly twenty years ago to speed redevelopment and ensure the construction of much-need earthquake-resistant housing: TAMA 38 and Pinui Binui. You can read details regarding the differences of these programs in Alster’s article, if you want. The gist is that they have gotten local residents themselves to actually choose to have their condo buildings redeveloped in order to add more units. One program tends to result in the addition of floors of a single building, while the other promotes demolition and rebuilding of clusters of buildings.

What explains the about face? Simple: the programs ensure that current local residents directly benefit from redevelopment. Should two thirds of the residents agree (note: the rate used to be 80 percent), then they can develop a plan and choose a developer to redevelop their homes. They get a new better-built unit, usually with additional floor space, balconies, and/or underground parking, while the developer makes a profit by selling the additional units. In essence, homeowners get a renovated and higher-value apartment for a relatively low cost: simply the inconvenience of having to relocated to temporary housing (often arranged for in the deal with the developer). It’s a classic case of a win-win.

But what about the stalwart NIMBYs, those who oppose change no matter what? The developer can sue them to participate (that is, if two-thirds of residents are in agreement). The holdouts have to provide a compelling reason in court: the deal is unfair, the developer hasn’t provided strong enough guarantees they can complete the job, or temporary housing hasn’t been provided. Opponents can’t just be simply trying to extract extra benefits for themselves by being stodgy.

The most fascinating part of the story is how large the effect of this small policy change has been on attitudes on redevelopment. Alster cites his own research showing that more objections have been filed in Tel Aviv-Jaffa in order to upzone regeneration schemes than to downzone them. That is, residents have more often demanded “that the plan should add more building rights, not less,” when TAMA 38 or Pinui Binui has been used.

Toward Democratic Urban Leadership

No doubt that these policies can’t simply be copied to America, where the problem is mainly one of excess housing (and infrastructural) costs. As dire as the problem may seem to hopeful homebuyers, it lacks the urgency of homes failing to meet earthquake standards. And the Israelis process, especially for Pinui Binui, can often require lengthy and expensive rezoning, which would be even more heated in a country where R1 single-family zoning has become almost sacrosanct. Then there’s the challenge of how to encourage owners of detached houses to decide to want to live with adjoining walls with someone else. TAMA 38 and Pinui Binui work for Israelis who already live in apartments, and who have less to lose. The cultural challenges are far more immense.

Nevertheless, the example is useful as a provocation, to get us to think in a more productive way about NIMBYs, and about politics in general. We often take it for granted that certain conflicts are simply zero-sum. My gain will have to be some else’s loss. Or, for the more politically arrogant, someone else needs to be forced “to win,” albeit according to *my* terms.

Because of the human tendency to become dogmatically incurious about our opponents’ opposition, especially in polarized societies, we too often yearn for stronger sticks or top-down control to beat opponents into submission. Politics is rarely so easy. Statewide laws to force densification in California and Montana have fallen, for instance, after opponents fought them on constitutional grounds. Instead, we need solutions that create more winners and limit minority veto power to situations in which people are genuinely being taken advantage of or political rights are being violated. Most importantly, we need solutions that let the people most affected by decisions have a say. Their influence should entail far more than just saying either “yes” or “no.”

…we could slowly turn many of our fanatical, seemingly existential, zero-sum political battles into more productive political confrontations.

Democratic leadership, if the word is to have any meaning at all, entails politicians using their power and discretion to make political decisions more representative than could otherwise be achieved by the inevitably imperfect and constrained mechanism of voting, to find creative ways to enable collective action to rise from the tumultuous grounds of conflict. From one perspective, it is exactly this capacity that elections should be able to select for. The candidate who is able to appeal to the interests of a broad swatch of the electorate and to stitch together a supportive coalition, should have sufficient insight into citizens’ diversity interests, needs, and disagreements in order to proposal and implement sustainable policy compromises.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t happen automatically. But, by demanding this level of thoughtfulness from not just politicians but also from each other, we could slowly turn many of our fanatical, seemingly existential, zero-sum political battles into more productive political confrontations. Making friends is a far more sure way to influence politics than earning oneself enemies. But it demands more humility and curiosity than we’re accustomed to. Being effective rather than just "right” always does.